|

Indian National Congress |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Abbreviation | INC |

| President | Mallikarjun Kharge [1][2] |

| General Secretary |

|

| Presidium | All India Congress Committee |

| Parliamentary Chairperson | Sonia Gandhi[3] |

| Lok Sabha Leader | Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury |

| Rajya Sabha Leader | Mallikarjun Kharge |

| Founder | Allan Octavian Hume[4] |

| Founded | 28 December 1885 (137 years ago) |

| Headquarters | 24, Akbar Road, New Delhi-110001[5] |

| Student wing | National Students’ Union of India |

| Youth wing | Indian Youth Congress |

| Women’s wing | All India Mahila Congress |

| Labour wing | Indian National Trade Union Congress |

| Peasant’s wing | Kisan and Khet Mazdoor Congress[6] |

| Membership | 45 million (2022)[7][8] |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Centre[23] to centre-left[27] |

| International affiliation | Progressive Alliance[28] Socialist International[29] |

| Colours | Sky blue (customary)[30][31] |

| ECI Status | National Party[32] |

| Alliance | United Progressive Alliance (All India) Secular Progressive Alliance (Tamil Nadu) Mahagathbandhan (Bihar) Mahagathbandhan (Jharkhand) Secular Democratic Forces (Tripura) Secular Progressive Front (Manipur) United Democratic Front (Kerala) Maha Vikas Aghadi (Maharashtra) |

| Seats in Lok Sabha |

50 / 543 (540 MPs & 3 Vacant) |

| Seats in Rajya Sabha |

31 / 245 (239 MPs & 6 Vacant)[33] |

| Seats in State Legislative Assemblies |

725 / 4,036 (4030 MLAs & 6 Vacant) (see complete list) |

| Seats in State Legislative Councils |

55 / 426 (390 MLCs & 36 Vacant) (see complete list) |

| Number of states and union territories in government |

7 / 31 (28 States & 3 UTs) |

| Election symbol | |

|

|

| Party flag | |

|

|

| Website | |

| www.inc.in |

|

|

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party or simply the Congress, is an Indian political party.[34] Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Empire in Asia and Africa.[a][35] From the late 19th century, and especially after 1920, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, the Congress became the principal leader of the Indian independence movement.[36] The Congress led India to independence from the United Kingdom,[d] and significantly influenced other anti-colonial nationalist movements in the British Empire.[e][35]

Congress is one of the two major political parties in India, along with its main rival the Bharatiya Janata Party.[39] It is a «big tent» party whose platform is generally considered to lie in the centre to centre-left of Indian politics.[21][16][40] After Indian independence in 1947, Congress emerged as a catch-all and secular party, dominating Indian politics for the next 20 years. The party’s first Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, led the Congress to support socialist policies by creating the Planning Commission, introducing Five-Year Plans, implementing a mixed economy, and establishing a secular state. After Nehru’s death and the short tenure of Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi became the leader of the party.

In 1969, the party suffered a major split, with a faction led by Indira Gandhi leaving to form the Congress (R), with the remainder becoming the Congress (O). The Congress (R) became the dominant faction, winning the 1971 general election with a huge margin. However, another split occurred in 1979, leading to the creation of the Congress (I), which was recognized as the Congress by the Electoral Commission in 1981. Under Rajiv Gandhi’s leadership, the party won a massive victory in the 1984 general elections, nevertheless losing the election held in 1989 to the National Front. The Congress then returned to power under P. V. Narasimha Rao, who moved the party towards an economically liberal agenda, a sharp break from previous leaders. However, it lost the 1996 general election and was replaced in government by the National Front (then the BJP). After a record eight years out of office, the Congress-led coalition known as the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) under Manmohan Singh formed a government post-winning 2004 general elections. Subsequently, the UPA again formed the government after winning the 2009 general elections, and Singh became the first Prime Minister since Nehru in 1962 to be re-elected after completing a full five-year term. However, in the 2014 general election, the Congress suffered a heavy defeat, winning only 44 seats of the 543-member Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Parliament of India). In the 2019 general election, the party again suffered a heavy defeat, winning only 52 seats in the Lok Sabha.

In the 17 general elections since independence, it has won an outright majority on seven occasions and has led the ruling coalition a further three times, heading the central government for more than 54 years. There have been six Prime Ministers from the Congress party, the first being Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1947–1964), and the most recent Dr. Manmohan Singh (2004–2014).

On social issues, it advocates secular policies that encourage equal opportunity, right to health, right to education, civil liberty, and support social market economy, and a strong welfare state. Being a centre-left party, its policies predominantly reflected balanced positions including secularism, egalitarianism, and social stratification.[21] The INC supports contemporary economic reforms such as liberalisation, privatisation and globalization. A total of 61 people have served as the president of the INC since its formation. Sonia Gandhi is the longest-serving president of the party, having held office for over twenty years from 1998 to 2017 and again from 2019 till 2022. Mallikarjun Kharge is the current serving President. The district party is the smallest functional unit of Congress. There is also a Pradesh Congress Committee (PCC), present at the state level in every state. Together, the delegates from the districts and PCCs form the All India Congress Committee (AICC). The party is also organized into several committees and sections, such as the Congress Working Committee (CWC).

History

Foundation

First session of Indian National Congress, Bombay, 28–31 December 1885

The Indian National Congress conducted its first session in Bombay from 28 to 31 December 1885 at the initiative of retired Civil Service officer Allan Octavian Hume, known for his pro-Indian activities.[41] In 1883, Hume had outlined his idea for a body representing Indian interests in an open letter to graduates of the University of Calcutta.[42][43] It aimed to obtain a greater share in government for educated Indians and to create a platform for civic and political dialogue between them and the British Raj. Hume took the initiative, and in March 1885 a notice convening the first meeting of the Indian National Union to be held in Poona the following December was issued.[44] However due to a cholera outbreak there, it was moved to Bombay.[45][46]

Hume organized the first meeting in Bombay with the approval of the Viceroy Lord Dufferin. Umesh Chandra Banerjee was the first president of Congress; the first session was attended by 72 delegates, representing each province of India.[47][48] Notable representatives included Scottish ICS officer William Wedderburn, Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta of the Bombay Presidency Association, Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, social reformer and newspaper editor Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Justice K. T. Telang, N. G. Chandavarkar, Dinshaw Wacha, Behramji Malabari, journalist, and activist Gooty Kesava Pillai, and P. Rangaiah Naidu of the Madras Mahajana Sabha.[49][50] This small elite group, unrepresentative of the Indian masses at the time,[51] functioned more as a stage for elite Indian ambitions than a political party for the first decade of its existence.[52]

Early years

At the beginning of the 20th century, Congress’ demands became more radical in the face of constant opposition from the British government, and the party decided to advocate in favour of the independence movement because it would allow a new political system in which Congress could be a major party. By 1905, a division opened between the moderates led by Gokhale, who downplayed public agitation, and the new extremists who advocated agitation, and regarded the pursuit of social reform as a distraction from nationalism. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who tried to mobilise Hindu Indians by appealing to an explicitly Hindu political identity displayed in the annual public Ganapati festivals he inaugurated in western India, was prominent among the extremists.[53]

Congress included several prominent political figures. Dadabhai Naoroji, a member of the sister Indian National Association, was elected president of the party in 1886 and was the first Indian Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons (1892–1895). Congress also included Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Jinnah was a member of the moderate group in the Congress, favouring Hindu–Muslim unity in achieving self-government.[54] Later he became the leader of the Muslim League and instrumental in the creation of Pakistan. Congress was transformed into a mass movement by Surendranath Banerjee during the partition of Bengal in 1905, and the resultant Swadeshi movement.[50]

Congress as a mass movement

Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru during a meeting of the All India Congress, in 1946

In 1915, Mahatma Gandhi returned from South Africa and joined Congress.[55][56] His efforts in South Africa were well known not only among the educated but also among the masses. During 1917 and 1918, Mahatma Gandhi was involved in three struggles– known as Champaran Satyagraha, Ahmedabad Mill Strike and Kheda Satyagraha.[57][58][59] After the First World War, the party came to be associated with Gandhi, who remained its unofficial spiritual leader and icon.[60] He formed an alliance with the Khilafat Movement in 1920 as part of his opposition to British rule in India,[61] and fought for the rights for Indians using civil disobedience or Satyagraha as the tool for agitation.[62] In 1922, after the deaths of policemen at Chauri Chaura, Gandhi suspended the agitation.

With the help of the moderate group led by Gokhale, in 1924 Gandhi became president of Congress.[63][64] The rise of Gandhi’s popularity and his satyagraha art of revolution led to support from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, Khan Mohammad Abbas Khan, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Chakravarti Rajgopalachari, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Jayaprakash Narayan, Jivatram Kripalani, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. As a result of prevailing nationalism, Gandhi’s popularity, and the party’s attempts at eradicating caste differences, untouchability, poverty, and religious and ethnic divisions, Congress became a forceful and dominant group.[65][66][67] Although its members were predominantly Hindu, it had members from other religions, economic classes, and ethnic and linguistic groups.[68]

Flag adopted by INC, 1931

At the Congress 1929 Lahore session under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, Purna Swaraj (complete independence) was declared as the party’s goal, declaring 26 January 1930 as Purna Swaraj Diwas (Independence Day). The same year, Srinivas Iyenger was expelled from the party for demanding full independence, not just home rule as demanded by Gandhi.[70]

After the passage of the Government of India Act 1935, provincial elections were held in India in the winter of 1936–37 in eleven provinces: Madras, Central Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, United Provinces, Bombay Presidency, Assam, NWFP, Bengal, Punjab, and Sindh. The final results of the elections were declared in February 1937.[71] The Indian National Congress gained power in eight of them – the three exceptions being Bengal, Punjab, and Sindh.[71] The All-India Muslim League failed to form a Government in any Province.[72]

Congress Ministers Resigned in October and November 1939 in Protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow’s declaration that India was a belligerent in the Second World War without consulting the Indian people.[73] In 1939, Subhas Chandra Bose, the elected President of India in both 1938 and 1939, resigned from Congress over the selection of the working committee.[74] Congress was an umbrella organisation, sheltering radical socialists, traditionalists, and Hindu and Muslim conservatives. Mahatma Gandhi expelled all the socialist groupings, including the Congress Socialist Party, the Krishak Praja Party, and the Swaraj Party, along with Subhas Chandra Bose, in 1939.[60]

After the failure of the Cripps Mission launched by the British government to gain Indian support for the British war effort, Mahatma Gandhi made a call to «Do or Die» in his Quit India movement delivered in Bombay on 8 August 1942 at the Gowalia Tank Maidan and opposed any help to the British in World War 2.[75] The British government responded with mass arrests including that of Gandhi and Congress leaders and killed over 1,000 Indians who participated in this movement.[76] A number of violent attacks were also carried out by the nationalists against the British government.[77] The movement played a role in weakening the control over the South Asian region by the British regime and ultimately paved the way for Indian independence.[77][78]

In 1945, when World War 2 almost came to an end, the Labour Party of the United Kingdom won elections with a promise to provide independence to India.[79][80] The jailed political prisoners of the Quit India movement were released in the same year.[81]

In 1946, the British tried the soldiers of Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army in the INA trials. In response, Congress helped form the INA Defence Committee, which assembled a legal team to defend the case of the soldiers of the Azad Hind government. The team included several famous lawyers, including Bhulabhai Desai, Asaf Ali, and Jawaharlal Nehru.[82] The British Empire eventually backtracked in the face of opposition by the Congress.[83][84]

Post-independence

After Indian independence in 1947, the Indian National Congress became the dominant political party in the country. In 1952, in the first general election held after Independence, the party swept to power in the national parliament and most state legislatures. It held power nationally until 1977 when it was defeated by the Janata coalition. It returned to power in 1980 and ruled until 1989 when it was once again defeated. The party formed the government in 1991 at the head of a coalition, as well as in 2004 and 2009 when it led the United Progressive Alliance. During this period the Congress remained centre-left in its social policies while steadily shifting from a socialist to a neoliberal economic outlook.[85] The Party’s rivals at state level have been national parties including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPIM), and various regional parties, such as the Telugu Desam Party, Trinamool Congress and Aam Aadmi Party.[86]

A post-partition successor to the party survived as the Pakistan National Congress, a party which represented the rights of religious minorities in the state. The party’s support was strongest in the Bengali-speaking province of East Pakistan. After the Bangladeshi War of Independence, it became known as the Bangladeshi National Congress, but was dissolved in 1975 by the government.[87][88][89]

Nehru and Shastri era (1947–1966)

From 1951 until his death in 1964, Jawaharlal Nehru was the paramount leader of the party. Congress gained power in landslide victories in the general elections of 1951–52, 1957, and 1962.[90] During his tenure, Nehru implemented policies based on import substitution industrialisation, and advocated a mixed economy where the government-controlled public sector co-existed with the private sector.[91] He believed the establishment of basic and heavy industries was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy.[90] The Nehru government directed investment primarily into key public sector industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies.[91] Nehru embraced secularism, socialistic economic practices based on state-driven industrialisation, and a non-aligned and non-confrontational foreign policy that became typical of the modern Congress Party.[92] The policy of non-alignment during the Cold War meant Nehru received financial and technical support from both the Eastern and Western Blocs to build India’s industrial base from nothing.[93][94]

During his period in office, there were four known assassination attempts on Nehru.[95] The first attempt on his life was during partition in 1947 while he was visiting the North-West Frontier Province in a car. The second was by a knife-wielding rickshaw-puller in Maharashtra in 1955.[96] A third attempt happened in Bombay in 1956.[97] The fourth was a failed bombing attempt on railway tracks in Maharashtra in 1961.[95] Despite threats to his life, Nehru despised having excess security personnel around him and did not like his movements to disrupt traffic.[95] K. Kamaraj became the president of the All India Congress Committee in 1963 during the last year of Nehru’s life.[98] Prior to that, he had been the chief minister of Madras state for nine years.[99] Kamaraj had also been a member of «the syndicate», a group of right wing leaders within Congress. In 1963 the Congress lost popularity following the defeat in the Indo-Chinese war of 1962. To revitalise the party, Kamaraj proposed the Kamaraj Plan to Nehru that encouraged six Congress chief ministers (including himself) and six senior cabinet ministers to resign to take up party work.[100][101][102]

In 1964, Nehru died because of an aortic dissection, raising questions about the party’s future.[103][104][105] Following the death of Nehru, Gulzarilal Nanda was appointed as the interim Prime Minister on 27 May 1964, pending the election of a new parliamentary leader of the Congress party who would then become Prime Minister.[106] During the leadership contest to succeed Nehru, the preference was between Morarji Desai and Lal Bahadur Shashtri. Eventually, Shashtri was selected as the next parliamentary leader thus the Prime Minister. Kamaraj was widely credited as the «kingmaker» in for ensuring the victory of Lal Bahadur Shastri over Morarji Desai.[107]

As prime minister, Shastri retained most of members of Nehru’s Council of Ministers; T. T. Krishnamachari was retained as Finance Minister of India, as was Defence Minister Yashwantrao Chavan.[108] Shastri appointed Swaran Singh to succeed him as External Affairs Minister.[109] Shastri appointed Indira Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter and former party president, Minister of Information and Broadcasting.[110] Gulzarilal Nanda continued as the Minister of Home Affairs.[111] As Prime Minister, Shastri continued Nehru’s policy of non-alignment,[112] but built closer relations with the Soviet Union. In the aftermath of the Sino-Indian War of 1962, and the formation of military ties between China and Pakistan, Shastri’s government expanded the defence budget of India’s armed forces. He also promoted the White Revolution—a national campaign to increase the production and supply of milk by creating the National Dairy Development Board.[113] The Madras anti-Hindi agitation of 1965 occurred during Shastri’s tenure.[114][115]

Shastri became a national hero following victory in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.[116] His slogan, «Jai Jawan Jai Kisan» («Hail the soldier, Hail the farmer»), became very popular during the war.[117] On 11 January 1966, a day after signing the Tashkent Declaration, Shastri died in Tashkent, reportedly of a heart attack; but the circumstances of his death remain mysterious.[118][119][120] After Shastri’s death, Congress elected Indira Gandhi as leader over Morarji Desai. Once again, K. Kamaraj was instrumental in achieving this result. The differences among the top leadership of the Congress regarding the future of the party during resulted in the formation of several breakaway parties such as Orissa Jana Congress, Bangla Congress, Utkal Congress, and, Bharatiya Kranti Dal.

Indira era (1966–1984)

In 1967, following a poor performance in the 1967 Indian general election, Indira Gandhi started moving toward the political left. On 12 July 1969, Congress Parliamentary Board nominated Neelam Sanjiva Reddy as Congress’s candidate for the post of President of India by a vote of four to two. K. Kamaraj, Morarji Desai and S. K. Patil voted for Reddy. Indira Gandhi and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed voted for V. V. Giri and Congress President S. Nijalingappa, Home Minister Yashwantrao Chavan and Agriculture Minister Jagjivan Ram abstained from voting.[121][122]

In mid-1969, she was involved in a dispute with senior party leaders on several issues. Notably – Her support for the independent candidate, V. V. Giri, rather than the official Congress party candidate, Neelam Sanjiva Reddy, for the vacant post of the president of India[123][124] and Gandhi’s abrupt nationalisation of the 14 biggest banks in India.

Congress split, 1969

In November 1969, the Congress party president, S. Nijalingappa, expelled Indira Gandhi from the party for indiscipline.[126] Subsequently Gandhi launched her own faction of the INC which came to be known as Congress (R).[f] The original party then came to be known as Indian National Congress (O).[g] Its principal leaders were Kamraj, Morarji Desai, Nijalingappa and S. K. Patil who stood for a more right-wing agenda.[127] The split occurred when a united opposition under the banner of Samyukt Vidhayak Dal, won control over several states in the Hindi Belt.[128] Indira Gandhi, on the other side, wanted to use a populist agenda in order to mobilise popular support for the party.[127] Her faction, called Congress (R), was supported by most of the Congress MPs while the original party had the support of only 65 MPs.[129] In the All India Congress Committee, 446 of its 705 members walked over to Indira’s side. The «Old Congress» retained the party symbol of a pair of bullocks carrying a yoke while Indira’s breakaway faction was given a new symbol of a cow with a suckling calf by the Election Commission as the party election symbol. The Congress (O) eventually merged with other opposition parties to form the Janata Party.

«India might be an ancient country but was a young democracy and as such should remain vigilant against the domination of few over the social, economic or political systems. Banks should be publicly owned so that they catered to not just large industries and big businesses but also agriculturists, small industries and entrepreneurs. Furthermore, the private banks had been functioning erratically with hundreds of them failing and causing loss to the depositors who were given no guarantee against such loss.»

—Gandhi’s remarks after the nationalisation of private banks.[130]

In the mid-term 1971 Indian general election, the Gandhi-led Congress (R) won a landslide victory on a platform of progressive policies such as the elimination of poverty (Garibi Hatao).[131] The policies of the Congress (R) under Gandhi before the 1971 elections included proposals to abolish the Privy Purse to former rulers of the Princely states, and the 1969 nationalisation of India’s 14 largest banks.[132] The 1969 attempt by Indira Gandhi government to abolish privy purse and the official recognition of the titles did not meet with success. The constitutional Amendment bill to this effect was passed in Lok Sabha, but it failed to get the required two-thirds majority in the Rajya Sabha. However, in 1971, with the passage of the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the Constitution of India, the privy purses were abolished.

Due to Sino-Indian War 1962, India faced a huge budgetary deficit resulting in its treasury being almost empty, high inflation, and dwindling forex reserves. The brief War of 1962 exposed weaknesses in the economy and shifted the focus towards the defence industry and the Indian Army. The government found itself short of resources to fund the Third Plan (1961–1966). Subhadra Joshi a senior party member, proposed a non-official resolution asking for the nationalisation of private banks stating that nationalisation would help in mobilising resources for development.[133] In July 1969, Indira Gandhi through the ordinance nationalised fourteen major private banks.[134] After being re-elected in 1971 on a campaign that endorsed nationalisation, Indira Gandhi went on to nationalise the coal, steel, copper, refining, cotton textiles and insurance industries. The main reason was to protect employment and the interest of the organised labour.[133]

On 12 June 1975, the High Court of Allahabad declared Indira Gandhi’s election to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s parliament, void on the grounds of electoral malpractice.[135] However, Gandhi rejected calls to resign and announced plans to appeal to the Supreme Court. In response to increasing disorder and lawlessness, Gandhi’s ministry recommended that President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed declare a State of Emergency, based on the provisions of Article 352 of the Constitution.[136] During the nineteen-month emergency, widespread oppression and abuse of power by Gandhi’s unelected younger son and political heir Sanjay Gandhi and his close associates occurred.[137][138][139] Implemented on 25 June 1975, the Emergency officially ended on 21 March 1977.[140] All political prisoners were released and fresh elections for the Lok Sabha were called.[141] In parliamentary elections held in March, the Janata alliance of anti-Indira opposition parties won a landslide victory over Congress, winning 295 seats in the Lok Sabha against Congress’ 153. Gandhi lost her seat to her Janata opponent Raj Narain.

Formation of Congress (I)

On 2 January 1978,Indira and her followers seceded and formed a new opposition party, popularly called Congress (I)—the «I» signifying Indira.[142] During the next year, her new party attracted enough members of the legislature to become the official opposition.[143] In November 1978, Gandhi regained a parliamentary seat. In January 1980, following a landslide victory for Congress (I), she was again elected prime minister.[144] The national election commission declared Congress (I) to be the real Indian National Congress for the 1984 general election.[citation needed] However, the designation I was dropped only in 1996.[143][144]

Punjab crisis

Gandhi’s premiership witnessed increasing turmoil in Punjab, with demands for Sikh autonomy by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his militant followers.[145] In 1983, Bhindranwale with his armed followers headquartered themselves in the Golden Temple in Amritsar and started accumulating weapons.[146] In June 1984, after several futile negotiations, Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to enter the Golden Temple to establish control over the complex and remove Bhindranwale and his armed followers. This event is known as Operation Blue Star.[147] On 31 October 1984, two of Gandhi’s bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, shot her with their service weapons in the garden of the prime minister’s residence in response to her authorisation of Operation Blue Star.[146] Gandhi was due to be interviewed by British actor Peter Ustinov, who was filming a documentary for Irish television.[148] Her assassination prompted the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, during which 3,000–17,000 people were killed.[149][150][151][152]

Rajiv Gandhi and Rao era (1984–1998)

Rajiv Gandhi addressing the Special Session of the United Nations on Disarmament, in New York City in June 1988

In 1984, Indira Gandhi’s son Rajiv Gandhi became nominal head of Congress, and went on to become prime minister upon her assassination.[153] In December, he led Congress to a landslide victory, where it secured 401 seats in the legislature.[154] His administration took measures to reform the government bureaucracy and liberalise the country’s economy.[155] Rajiv Gandhi’s attempts to discourage separatist movements in Punjab and Kashmir backfired. After his government became embroiled in several financial scandals, his leadership became increasingly ineffectual.[156] Gandhi was regarded as a non-abrasive person who consulted other party members and refrained from hasty decisions.[157] The Bofors scandal damaged his reputation as an honest politician, but he was posthumously cleared of bribery allegations in 2004.[158] On 21 May 1991, Gandhi was killed by a bomb concealed in a basket of flowers carried by a woman associated with the Tamil Tigers.[159] He was campaigning in Tamil Nadu for upcoming parliamentary elections. In 1998, an Indian court convicted 26 people in the conspiracy to assassinate Gandhi.[160] The conspirators, who consisted of Tamil militants from Sri Lanka and their Indian allies, had sought revenge against Gandhi because the Indian troops he sent to Sri Lanka in 1987 to help enforce a peace accord there had fought with Tamil Militant guerrillas.[161][162]

Visit of Narasimha Rao to the CEC

Rajiv Gandhi was succeeded as party leader by P. V. Narasimha Rao, who was elected prime minister in June 1991.[163] His rise to the prime ministership was politically significant because he was the first holder of the office from South India. After the election, he formed minority government. Rao himself not contested elections in 1991, but after he was sworn in a prime minister, he won in a by-election from Nandyal in Andhra Pradesh.[164] His administration oversaw major economic change and experienced several home incidents that affected India’s national security.[165] Rao, who held the Industries portfolio, was personally responsible for the dismantling of the Licence Raj, which came under the purview of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.[166] He is often called the «father of Indian economic reforms».[167][168]

Future prime ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh continued the economic reform policies begun by Rao’s government. Rao accelerated the dismantling of the Licence Raj, reversing the socialist policies of previous governments.[169][170] He employed Manmohan Singh as his finance minister to begin a historic economic change. With Rao’s mandate, Singh launched India’s globalisation reforms that involved implementing International Monetary Fund (IMF) policies to prevent India’s impending economic collapse.[166] Rao was also referred to as Chanakya for his ability to push tough economic and political legislation through the parliament while he headed a minority government.[171][172]

By 1996, the party’s image was suffering from allegations of corruption, and in elections that year, Congress was reduced to 140 seats, its lowest number in the Lok Sabha to that point. Rao later resigned as prime minister and, in September, as party president.[173] He was succeeded as president by Sitaram Kesri, the party’s first non-Brahmin leader.[174] During the tenure of both Rao and Kesri, the two leaders conducted internal elections to the Congress working committees and their own posts as party presidents.[175]

INC (1998–present)

The 1998 general elections saw Congress win 141 seats in the Lok Sabha, its lowest tally until then.[176] To boost its popularity and improve its performance in the forthcoming election, Congress leaders urged Sonia Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi’s widow, to assume leadership of the party.[177] She had previously declined offers to become actively involved in party affairs and had stayed away from politics.[178] After her election as party leader, a section of the party that objected to the choice because of her Italian ethnicity broke away and formed the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), led by Sharad Pawar.[179]

Sonia Gandhi struggled to revive the party in her early years as its president; she was under continuous scrutiny for her foreign birth and lack of political acumen. In the snap elections called by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in 1999, Congress’ tally further plummeted to just 114 seats.[180] Although the leadership structure was unaltered as the party campaigned strongly in the assembly elections that followed, Gandhi began to make such strategic changes as abandoning the party’s 1998 Pachmarhi resolution of ekla chalo (go it alone) policy, and formed alliances with other like-minded parties. In the intervening years, the party was successful at various legislative assembly elections; at one point, Congress ruled 15 states.[181] For the 2004 general election, Congress forged alliances with regional parties including the NCP and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam.[182] The party’s campaign emphasised social inclusion and the welfare of the common masses—an ideology that Gandhi herself endorsed for Congress during her presidency—with slogans such as Congress ka haath, aam aadmi ke saath («Congress hand in hand with the common man»), contrasting with the NDA’s «India Shining» campaign.[180][183][184] The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) won 222 seats in the new parliament, defeating the NDA by a substantial margin. With the subsequent support of the communist front, Congress won a majority and formed a new government.[185] Despite massive support from within the party, Gandhi declined the post of prime minister, choosing to appoint Manmohan Singh instead.[186] She remained as party president and headed the National Advisory Council (NAC).[187]

During its first term in office, the UPA government passed several social reform bills. These included an employment guarantee bill, the Right to Information Act, and a right to education act. The NAC, as well as the Left Front that supported the government from the outside, were widely seen as being the driving force behind such legislation. The Left Front withdrew its support of the government over disagreements about the U.S.–India Civil Nuclear Agreement. Despite the effective loss of 62 seats in parliament, the government survived the trust vote that followed.[188] In the Lok Sabha elections held soon after, Congress won 207 seats, the highest tally of any party since 1991. The UPA as a whole won 262, enabling it to form a government for the second time. The social welfare policies of the first UPA government, and the perceived divisiveness of the BJP, are broadly credited with the victory.[189]

By the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the party had lost much of its popular support, mainly because of several years of poor economic conditions in the country, and growing discontent over a series of corruption allegations involving government officials, including the 2G spectrum case and the Indian coal allocation scam.[190][191] Congress won only 44 seats in the Lok Sabha, compared to the 336 of the BJP and its allies[192] The UPA suffered heavy defeat, which was its worst-ever performance in a national election with its vote share dipping below 20 per cent for the first time.[193] Narendra Modi succeeded Singh as Prime Minister as the head of the National Democratic Alliance. Sonia Gandhi retired as party president in December 2017, having served for a record nineteen years. She was succeeded by her son Rahul Gandhi, who was elected unopposed in the 2017 INC presidential election.[185]

Rahul Gandhi resigned from his post after the 2019 Indian general election, due to the party’s dismal performance.[194] Following Gandhi’s resignation, party leaders began deliberations for a suitable candidate to replace him. The Congress Working Committee met on 10 August to make a final decision on the matter and passed a resolution asking Sonia Gandhi to take over as interim president until a consensus candidate could be picked.[195][196] Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury is the leader of Congress in Lok Sabha.[197] Gaurav Gogoi is deputy leader in Lok Sabha, Ravneet Singh Bittu is whip.[198] Based on an analysis of the candidates’ poll affidavits, a report by the National Election Watch (NEW) and the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) says that, the Congress has highest political defection since 2014. According to the report, a total of 222 electoral candidates have left the Congress to join other parties during polls held between 2014 and 2021, whereas 177 MPs and MLAs quit the party.[199] Defection resulted loss of its established governments in Arunachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, Puducherry, and Manipur.

Presidential election

On 28 August 2022, the Congress Working Committee (CWC) decided to hold 2022 INC Presidential Election. The election will be held on 17 October 2022 and the counting will take place on 19 October 2022, if required. A formal notification for the election was issued on 22 September 2022.[200] The main two contenders were Shashi Tharoor and Mallikarjun Kharge.[201]

Mallikarjun Kharge won this election.[1] He secured 7,897 out of the 9,385 votes polled. His rival, Shashi Tharoor, however sprung a surprise by securing 1,072 votes.[2]

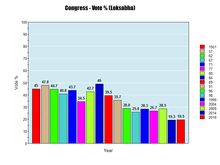

General election results

In the first parliamentary elections held in 1952, the INC won 364 seats, which was 76 per cent of the 479 contested seats. The vote share of the INC was 45 per cent of all votes cast. Till the 1971 general elections, the party’s voting percentage remain intact at 40 per cent. However, the 1977 general elections resulted in a heavy defeat for the INC. Many notable INC party leader lost their seats, winning only 154 seats in the Lok Sabha.[202] The INC again returned to power in the 1980 Indian general election securing a 42.7 per cent vote share of all votes, winning 353 seats. INC’s vote share kept increasing till 1980 and then to a record high of 48.1 per cent by 1984/85. Rajiv Gandhi on assuming the post of Prime Minister in October 1984 recommended early elections. The general elections were to be held in January 1985; instead, they were held in December 1984. The Congress won an overwhelming majority, securing 415 seats out of 533, the largest ever majority in independent India’s Lok Sabha elections history. This winning recorded a vote share of 49.1 per cent resulting in an overall increase to 48.1 per cent. The party got 32.14 per cent of voters in polls held in Punjab and Assam in 1985.

In November 1989, general elections were held to elect the members of the 9th Lok Sabha. The Congress did badly in the elections, though it still managed to be the largest single party in the Lok Sabha. Its vote share started decreasing to 39.5 per cent in the 1989 general elections. The 13th Lok Sabha term was to end in October 2004, but the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government decided on early polls. The Lok Sabha was dissolved in February itself and the country went to the polls in April–May 2004. The INC, led by Sonia Gandhi unexpectedly emerged as the single largest party.[203] After the elections, Congress joined up with minor parties to form the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). The UPA with external support from the Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Kerala Congress, and the Left Front managed a comfortable majority.[203] Congress has lost nearly 20% of its vote share in general elections held between 1996 and 2009.[199]

Congress Lok Sabha vote percentage all time

Congress Loksabha Seats all time

Congress Rajyasabha Seats all time

| Year | Legislature | Party leader | Seats won | Change in seats |

Percentage of votes |

Vote swing |

Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | 5th Central Legislative Assembly | Bhulabhai Desai |

42 / 147 |

— | — | — | [204] | |

| 1945 | 6th Central Legislative Assembly | Sarat Chandra Bose |

59 / 102 |

— | — | Interim Government of India (1946–1947) | [205] | |

| 1951 | 1st Lok Sabha | Jawaharlal Nehru |

364 / 489 |

44.99% | — | Government | [206] | |

| 1957 | 2nd Lok Sabha |

371 / 494 |

47.78% | Government | [207] | |||

| 1962 | 3rd Lok Sabha |

361 / 494 |

44.72% | Government | [208] | |||

| 1967 | 4th Lok Sabha | Indira Gandhi |

283 / 520 |

40.78% | Government (1967–69) Coalition (1969–71) |

[209] | ||

| 1971 | 5th Lok Sabha |

352 / 518 |

43.68% | Government | [210] | |||

| 1977 | 6th Lok Sabha |

153 / 542 |

34.52% | Opposition | [211] | |||

| 1980 | 7th Lok Sabha |

351 / 542 |

42.69% | Government | [144] | |||

| 1984 | 8th Lok Sabha | Rajiv Gandhi |

415 / 533 |

49.01% | Government | [212] | ||

| 1989 | 9th Lok Sabha |

197 / 545 |

39.53% | Opposition | [213] | |||

| 1991 | 10th Lok Sabha | P. V. Narasimha Rao |

244 / 545 |

35.66% | Government | [214] | ||

| 1996 | 11th Lok Sabha |

140 / 545 |

28.80% | Opposition, later outside support for UF | [215] | |||

| 1998 | 12th Lok Sabha | Sitaram Kesri |

141 / 545 |

25.82% | Opposition | [216][217] | ||

| 1999 | 13th Lok Sabha | Sonia Gandhi |

114 / 545 |

28.30% | Opposition | [218][219] | ||

| 2004 | 14th Lok Sabha |

145 / 543 |

26.7% | Coalition | [220] | |||

| 2009 | 15th Lok Sabha |

206 / 543 |

28.55% | Coalition | [221] | |||

| 2014 | 16th Lok Sabha | Rahul Gandhi |

44 / 543 |

19.3% | Opposition | [222] | ||

| 2019 | 17th Lok Sabha |

52 / 543 |

19.5% | Opposition | [223] |

Political positions

The Congress party emphasizes social equality, freedom, secularism, and equal opportunity.[13] Its political position is generally considered to be in the centre.[40] Historically, the party has represented farmers, labourers, and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA).[224] The MGNREGA was initiated with the objective of «enhancing livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year, to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.» Another aim of MGNREGA is to create durable assets (such as roads, canals, ponds, and wells).[224]

The Congress has positioned itself as both pro-Hindu and protector of the minorities. The party supports Mahatma Gandhi’s doctrine of Sarva Dharma Sama Bhava, collectively termed by its party members as secularism. Former Chief Minister of Punjab and senior Congress member Amarinder Singh said, «India belongs to all religions, which is its strength, and the Congress would not allow anyone to destroy its cherished secular values.»[225] On 9 November 1989, Rajiv Gandhi had allowed Shilanyas (foundation stone-laying ceremony) adjacent to the then disputed Ram Janmabhoomi site.[226] Subsequently, his government faced heavy criticism over the passing of The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act 1986, which nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Shah Bano case. The 1984 violence made the Congress party lose a moral argument over secularism. The BJP questioned the Congress party’s moral authority in questioning it about the 2002 Gujarat riots.[227] The Congress has distanced itself from Hindutva ideology, though the party has softened its stance after defeat in the 2014 and 2019 general elections.[228]

Under Narsimha Rao’s premiership, the Panchayati Raj and Municipal Government got constitutional status. With the enactment of the 73rd and 74th amendments to the constitution, a new chapter, Part- IX added to the constitution.[229] States have been given the flexibility to take into consideration their geographical, politico-administrative, and other consideration while adopting the Panchayati-raj system. In both panchayats and municipal bodies, in an attempt to ensure that there is inclusiveness in local self-government, reservations for SC/ST and women were implemented.[230]

After independence, Congress advocated the idea of establishing Hindi as the sole national language of India. Nehru led the faction of the Congress party which promoted Hindi as the lingua franca of the Indian nation.[231] However, the non-Hindi-speaking Indian states, especially Tamil Nadu, opposed it and wanted the continued use of the English language. Lal Bahadur Shastri’s tenure witnessed several protests and riots including the Madras anti-Hindi agitation of 1965.[232] Shashtri’s appealed to agitators to withdraw the movement and assured them that the English would continue to be used as the official language as long as the non-Hindi speaking states wanted.[233] Indira Gandhi assuaged the sentiments of the non-Hindi speaking states by getting the Official Languages Act amended in 1967 to provide that the use of English could continue until a resolution to end the use of the language was passed by the legislature of every state that had not adopted use Hindi as its official language, and by each house of the Indian Parliament.[234] This was a guarantee of de facto use of both Hindi and English as official languages, thus establishing bilingualism in India.[235] The step led to the end of the anti-Hindi protests and riots in states.

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which, among other things, criminalizes homosexuality; former Congress president Rahul Gandhi said, «Sexuality is a matter of personal freedom and should be left to individuals». Leading party figure and former Finance Minister P. Chidambaram stated that the Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India judgment must be quickly reversed». On 18 December 2015, Shashi Tharoor leading member of the party introduced a private member’s bill to replace Section 377 in the Indian Penal Code and decriminalize consensual same-sex relations. The bill was defeated in the first reading. In March 2016, Tharoor again reintroduce the private member’s bill to decriminalize homosexuality but was voted down for the second time.

Economic policies

The history of the economic policy of Congress-led governments can be divided into two periods. The first period lasted from independence, in 1947, to 1991 and put great emphasis on the public sector.[236] The second period began with economic liberalisation in 1991. At present, Congress endorses a mixed economy in which the private sector and the state both direct the economy, which has characteristics of both market and planned economies. The Congress advocates import substitution industrialisation—the replacement of imports with the domestic product, and believes the Indian economy should be liberalised to increase the pace of development.[237][238]

At the beginning of the first period, the Congress prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru implemented policies based on import substitution industrialisation and advocated a mixed economy where the government-controlled public sector would co-exist with the private sector. He believed that the establishment of basic and heavy industry was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy. The government, therefore, directed investment primarily into key public-sector industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies. This period was called the Licence Raj, or Permit Raj,[239] which was the elaborate system of licences, regulations, and accompanying red tape that were required to set up and run businesses in India between 1947 and 1990.[240] The Licence Raj was a result of Nehru and his successors’ desire to have a planned economy where all aspects of the economy were controlled by the state, and licences were given to a select few. Up to 80 government agencies had to be satisfied before private companies could produce something; and, if the licence were granted, the government would regulate production.[241] The licence raj system continued under Indira Gandhi. In addition, many key sectors such as banking, steel coal, and oil were nationalized.[129][242] Under Rajiv Gandhi, the trade regime were liberalised with reduction in duties on several import items and incentives to promote exports.[243] Tax rates were reduced and curbs on company assests loosened.[244]

In 1991, the new Congress government, led by P. V. Narasimha Rao, initiated reforms to avert the impending 1991 economic crisis.[168][245] The reforms progressed furthest in opening up areas to foreign investment, reforming capital markets, deregulating domestic business, and reforming the trade regime. The goals of Rao’s government were to reduce the fiscal deficit, privatise the public sector, and increase investment in infrastructure.[246] Trade reforms and changes in the regulation of foreign direct investment were introduced to open India to foreign trade while stabilising external loans.[247] Rao chose Manmohan Singh for the job. Singh, an acclaimed economist and former chairman of the Reserve Bank, played a central role in implementing these reforms.[248]

In 2004, Singh became prime minister of the Congress-led UPA government. Singh remained prime minister after the UPA won the 2009 general elections. The UPA government introduced policies aimed at reforming the banking and financial sectors, as well as public sector companies.[249] It also introduced policies aimed at relieving farmers of their debt.[250] In 2005, Singh government introduced the value-added tax, replacing the sales tax. India was able to resist the worst effects of the global economic crisis of 2008.[251][252] Singh’s government continued the Golden Quadrilateral, the Indian highway modernisation program that was initiated by Vajpayee’s government.[253] Then Finance Minister of India Pranab Mukherjee implemented many tax reforms, notably scrapping the Fringe Benefits Tax and the Commodities Transaction Tax.[254] He implemented the Goods and Services Tax (GST) during his tenure.[255] His reforms were well received by major corporate executives and economists. The introduction of retrospective taxation, however, has been criticised by some economists.[256] Mukherjee expanded funding for several social sector schemes including the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). He also supported budget increases for improving literacy and health care. He expanded infrastructure programmes such as the National Highway Development Programme.[257] Electricity coverage was also expanded during his tenure. Mukherjee also reaffirmed his commitment to the principle of fiscal prudence as some economists expressed concern about the rising fiscal deficits during his tenure, the highest since 1991. Mukherjee declared the expansion in government spending was only temporary.[258]

National defence and home affairs

Manmohan Singh and his wife during the passing out parade at the Platinum Jubilee Course of IMA on 10 December 2007; with foreign gentleman cadets.

Since its independence, India was in pursuing of nuclear capabilities, as Nehru felt that nuclear energy could take the country forward and help achieve its developmental goals.[259] Consequently, Nehru began to seek assistance from the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.[260][261] In 1958 the government of India with the help of Homi J. Bhabha adopted a three-phase power production plan and the Nuclear Research Institute was established in 1954.[262] Indira Gandhi witnessed continuous nuclear testing by China from 1964 onwards, which she considered an existential threat to India.[263][264] India conducted its first nuclear test in the Pokhran desert in Rajasthan on 18 May 1974, under the name Operation Smiling Buddha.[265] India asserted that the test was for «peaceful purposes», However, the test was criticized by other countries and the United States and Canada suspended all nuclear support to India.[266] Despite intense international criticism, the nuclear test was domestically popular and caused an immediate revival of Indira Gandhi’s popularity, which had flagged considerably from its heights after the 1971 war.[267][268]

The transition to statehood for parts of Northeast India was successfully overseen under Indira Gandhi’s premiership.[269] In 1972, her administration granted statehood to Meghalaya, Manipur and Tripura, while the North-East Frontier Agency was declared a union territory and renamed Arunachal Pradesh.[270][271] This was followed by the annexation of Sikkim in 1975.[272]

Manmohan Singh’s administration initiated a massive reconstruction effort in Kashmir to stabilize the region and strengthened anti-terrorism laws with amendments to the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).[273] After a period of initial success, insurgent infiltration and terrorism in Kashmir have increased since 2009. However, the Singh administration was successful in reducing terrorism in Northeast India.[274] Under the background of the Punjab insurgency, the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) was passed. The aim of the law is mainly directed toward eliminating the infiltrators from Pakistan. The law gave wide powers to law enforcement agencies for dealing with national terrorist and socially disruptive activities. The police were not obliged to produce a detainee before a judicial magistrate within 24 hours. The law was widely criticized by human rights organizations. After the November 2008 Mumbai terror attacks, the UPA government created the National Investigation Agency (NIA), in response to the need for a central agency to combat terrorism.[275] The Unique Identification Authority of India was established in February 2009 to implement the proposed Multipurpose National Identity Card, to increase national security.[276]

Education and healthcare

The Congress government under Nehru oversaw the establishment of many institutions of higher learning, including the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the Indian Institutes of Technology, the Indian Institutes of Management and the National Institutes of Technology. The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) was established in 1961 as a literary, scientific, and charitable Society under the Societies Registration Act.[277] Jawahar Lal Nehru outlined a commitment in his five-year plans to guarantee free and compulsory primary education to all of India’s children. Rajiv Gandhi’s premiership pioneered public information infrastructure and innovation in India.[278] His government allowed the import of fully assembled motherboards, which led to the price of computers being reduced.[279] The concept of having Navodaya Vidyalaya in every district of India was born as a part of the National Policy on Education (NPE).[280]

In 2005, The Congress-led government started the National Rural Health Mission, which employed about 500,000 community health workers. It was praised by economist Jeffrey Sachs.[281] In 2006, it implemented a proposal to reserve 27 per cent of seats in the All India Institute of Medical Studies (AIIMS), the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), and other central higher education institutions, for Other Backward Classes, which led to the 2006 Indian anti-reservation protests.[282] The Singh government also continued the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan program, which includes the introduction and improvement of mid-day school meals and the opening of new schools throughout India, especially in rural areas, to fight illiteracy.[283] During Manmohan Singh’s prime ministership, eight Institutes of Technology were opened in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Orissa, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh.[284]

Foreign policies

The aligned countries on the northern hemisphere: NATO in blue and the Warsaw Pact in red.

Throughout much of the Cold War period, Congress supported a foreign policy of non-alignment that called for India to form ties with both the Western and Eastern Blocs, but to avoid formal alliances with either.[285] US support for Pakistan led the party to endorse a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union in 1971.[286] Congress has continued the foreign policy started by P. V. Narasimha Rao. This includes the peace process with Pakistan, and the exchange of high-level visits by leaders from both countries.[287] The UPA government has tried to end the border dispute with the People’s Republic of China through negotiations.[288][289]

Relations with Afghanistan have also been a concern for Congress.[290] During Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s visit to New Delhi in August 2008, Manmohan Singh increased the aid package to Afghanistan for the development of schools, health clinics, infrastructure, and defence.[291] India is now one of the single largest aid donors to Afghanistan.[291] To nourish political, security, cultural and economical connections with central Asian countries, it launched Connect Central Asia policy in 2012. This policy is aimed at strengthening and expanding India’s relations with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Look East policy was initiated in 1992 by Narasimha Rao to cultivate extensive economic and strategic relations with the nations of Southeast Asia to bolster its standing as a regional power and a counterweight to the strategic influence of the People’s Republic of China. Subsequently, in 1992 Rao decided to bring into open India’s relations with Israel, which had been kept covertly active for a few years during his tenure as a Foreign Minister, and permitted Israel to open an embassy in New Delhi.[292] Rao decided to maintain a distance from the Dalai Lama to avoid aggravating Beijing’s suspicions and concerns, and made successful overtures to Tehran.[293]

Even though the Congress foreign policy doctrine stands for maintaining friendly relations with all the countries of the world, it has always exhibited a special bias towards the Afro-Asian nations. It played active role in forming Group of 77 (1964, Group of 15 (1990), Indian Ocean Rim Association, and SAARC. Indira Gandhi firmly tied Indian anti-imperialist interests in Africa to those of the Soviet Union. She openly and enthusiastically supported liberation struggles in Africa.[294] In April 2006, New Delhi hosted an India–Africa summit attended by the leaders of 15 African states.[295]

The party opposes arms race and advocates disarmament, both conventional and nuclear.[296] When in power between 2004 and 2014, Congress worked on India’s relationship with the United States. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh visited the US in July 2005 to negotiate an India–United States Civil Nuclear Agreement. US president George W. Bush visited India in March 2006; during this visit, a nuclear agreement that would give India access to nuclear fuel and technology in exchange for the IAEA inspection of its civil nuclear reactors was proposed. Over two years of negotiations, followed by approval from the IAEA, the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the United States Congress, the agreement was signed on 10 October 2008.[297] However, it has not signed Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) due to their discriminatory and hegemonistic nature.[298][299]

Congress’ policy has been to cultivate friendly relations with Japan as well as European Union countries including the United Kingdom, France, and Germany.[300] Diplomatic relations with Iran have continued, and negotiations over the Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline have taken place.[301] Congress’ policy has also been to improve relations with other developing countries, particularly Brazil and South Africa.[302]

Structure and composition

At present, the president and the All India Congress Committee (AICC) are elected by delegates from state and district parties at an annual national conference; in every Indian state and union territory—or pradesh—there is a Pradesh Congress Committee (PCC),[303] which is the state-level unit of the party responsible for directing political campaigns at local and state levels, and assisting the campaigns for parliamentary constituencies.[304] Each PCC has a working committee of twenty members, most of whom are appointed by the party president, the leader of the state party, who is chosen by the national president. Those elected as members of the states’ legislative assemblies form the Congress Legislature Parties in the various state assemblies; their chairperson is usually the party’s nominee for Chief Ministership. The party is also organised into various committees, and sections; it publishes a daily newspaper, the National Herald.[305] Despite being a party with a structure, Congress under Indira Gandhi did not hold any organisational elections after 1972.[306] Nonetheless, in 2004, when the Congress was voted back into power, Manmohan Singh became the first Prime Minister not to be the president of the party since establishment of the practice of the president holding both positions.[307]

The AICC is composed of delegates sent from the PCCs.[305] The delegates elect Congress committees, including the Congress Working Committee, consisting of senior party leaders and office-bearers. The AICC takes all-important executive and political decisions. Since Indira Gandhi formed Congress (I) in 1978, the President of the Indian National Congress has effectively been the party’s national leader, head of the organisation, head of the Working Committee and all chief Congress committees, chief spokesman, and Congress’ choice for Prime Minister of India. Constitutionally, the president is elected by the PCCs and members of the AICC; however, this procedure has often been bypassed by the Working Committee, which has elected its candidate.[305]

The Congress Parliamentary Party (CPP) consists of elected MPs in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. There is also a Congress Legislative Party (CLP) leader in each state. The CLP consists of all Congress Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in each state. In cases of states where the Congress is single-handedly ruling the government, the CLP leader in the chief minister. Other directly affiliated groups include:

- National Students’ Union of India (NSUI), the students’ wing of the Congress.

- Indian Youth Congress, the party’s youth wing.

- Indian National Trade Union Congress, the labour union.

- All India Mahila Congress, its women’s division.

- Congress Seva Dal, its voluntary organisation.[308][309]

- All India Congress Minority Department, also referred to as Minority Congress is the minority wing of the Congress party. It is represented by the Pradesh Congress Minority Department in all the states of India.[310]

Election symbols

Election symbol of Congress (R) party during the period 1971–1977

As of 2021, the election symbol of Congress, as approved by the Election Commission of India, is an image of a right hand with its palm facing front and its fingers pressed together;[311] this is usually shown in the center of a tricolor flag. The hand symbol was first used by Indira Gandhi when she split from the Congress (R) faction following the 1977 elections and created the New Congress (I).[312] The hand is symbolic of strength, energy, and unity.

The party under the stewardship of Nehru had the symbol ‘Pair of bullocks carrying a yoke’ which struck a chord with masses who were predominantly farmers.[313] In 1969, due to internal conflicts within the Congress party, Indira Gandhi decided to break out and form a party of her own, with the majority of the Congress party members in support of her in the new party which was named Congress(R). The symbol of Indira’s Congress (R) or Congress (Requisitionists) during the 1971–1977 period was a cow with a suckling calf.[314][127] After losing the support of 76 out of the party’s 153 members in the Lok Sabha, Indira’s new political outfit the Congress (I) or Congress (Indira) evolved and she opted for the hand (open palm) symbol.

Dynasticism

Dynasticism is fairly common in many political parties in India, including the Congress party.[315] Six members of the Nehru–Gandhi family have been presidents of the party.[316] The party started being controlled by Indira Gandhi’s family during the emergency with her younger son, Sanjay taking on a prominent role.[317] This was characterized by servility and sycophancy towards the family which later led to a hereditary succession of Rajiv Gandhi as successor after Indira Gandhi’s assassination, as well as the party’s selection of Sonia Gandhi as Rajiv’s successor after his assassination, which she turned down.[318] Since the formation of Congress (I) by Indira Gandhi in 1978, the party president has been from her family except for the period between 1991 and 1998. In the last three elections to the Lok Sabha combined, 37 per cent of Congress party MPs had family members precede them in politics.[319] However, in recent times there have been calls from within the party to restructure the organization. A group of senior leaders wrote a letter to the party president to reform the Congress allowing others to take charge. There was also visible discontent post the loss in 2019 elections after which a group of 23 senior leaders wrote to the Congress President to restructure the party.[320]

Presence/Alliance in states and UTs

From the first general election in 1952 when Jawaharlal Nehru led it to a landslide victory, the Congress won in the majority of the following state elections and paved the way for a Nehruvian era of single-party dominance. The party during the post-independence era has governed most of the States and union territories of India.[321]

As of May 2023, the INC is in power in the states of Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, and Karnataka. where the party has the majority.[322] In Maharashtra, it shared power as a junior ally with alliance partners Nationalist Congress Party, Shiv Sena and other smaller regional parties under the multi-party Maha Vikas Aghadi coalition from 2019 until June 2022.[323][324] In Jharkhand, it shares power as a junior ally with Jharkhand Mukti Morcha.[325] In Tamil Nadu its a junior ally of the DMK, CPI, CPI(M), VCK under the coalition Secular Progressive Alliance or SPA . The Congress has previously been the sole party in power in Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, Meghalaya, Haryana, Uttarakhand and in the Union Territory of Puducherry. The Congress has never been a part of the government in Telangana, however, the Congress has been in the power in Andhra Pradesh before the state was bifurcated. Congress has enjoyed overwhelming electoral majority for over decades in Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Kerala, Maharashtra and Punjab. It has a regional political alliance in Tamil Nadu named the Secular Progressive Alliance, and in Kerala, it is the United Democratic Front.[326][327]

| S.No. | State/UT | UPA Govt Since | Chief Minister | Party/alliance partner | Seats in Assembly |

Last election | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Party | Seats | Since | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Ind. | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Chhattisgarh | 17 December 2018 | Bhupesh Baghel | INC | 70 | 17 December 2018 | None | 70/90 | 11 December 2018 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Rajasthan | 17 December 2018 | Ashok Gehlot | INC | 108 | 17 December 2018 | RLD (1) | None | 12 | 117/200 | 11 December 2018 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Himachal Pradesh | 8 December 2022 | Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu | INC | 40 | 11 December 2022 | None | 40/68 | 8 December 2022 | |||||||||||||

| 4 | Karnataka | 14 May 2023 | Siddaramaiah | INC | 135 | 20 May 2023 | SKP (1) | None | 1 | 137/224 | 10 May 2023 | |||||||||||

| Alliances | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Jharkhand | 28 December 2019 | Hemant Soren | JMM | 30 | 28 December 2019 | INC (18) | RJD (1) | NCP (1) | CPI(ML)L (1) | None | 50/81 | 23 December 2019 | |||||||||

| 6 | Tamil Nadu | 7 May 2021 | M. K. Stalin | DMK | 133 | 7 May 2021 | INC (18) | VCK (4) | CPI (2) | CPI(M) (2) | None | 159/234 | 6 April 2021 | |||||||||

| 7 | Bihar | 10 August 2022 | Nitish Kumar | JD(U) | 45 | 10 August 2022 | RJD (79) | INC (19) | CPI(ML)L (12) | CPI (2) | CPI(M) (2) | HAM(S) (4) | 1 | 164/243 | 10 August 2022 |

Legislative leaders

List of prime ministers

The Congress has governed a majority of the period of independence India (for 55 years), whereby Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Manmohan Singh are the country’s longest-serving prime ministers. The first general election the Congress contested after the Indian independence was in 1951–52 general elections, in which it won 364 of the 489 seats and 45 per cent of the total votes.[328] The Indian National Congress became the largest party in the Lok Sabha for next five consecutive general elections.

Gulzarilal Nanda took office in 1966 following the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri for 13 days as the acting Prime Minister of India.[329] His earlier 13-day stint as the second Prime Minister of India followed the death of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964. Indira Gandhi, also the first and so far the only woman Prime Minister of India, served the second-longest term as a prime minister.[330] Rajiv Gandhi served from 1984 to 1989. He took office on the day of the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984 after the Sikh riots and at age 40 was the youngest PM of India. Known for economic reforms that were brought under his tenure, PV Narasimha Rao served as the 10th prime minister of India. He was also the first PM to come from southern India.[331] The Congress party and its allies achieved a majority in the Lok Sabha in 2004 and 2009 general elections. Manmohan Singh served two complete terms as the Prime Minister and headed United Progressive Alliance (UPA) governments two times. Though party suffered a heavy defeat in general elections held in 2014 and 2019. As of June 2021, there are 34 members of the party in Rajya Sabha (upper house of the parliament).[33]

| No. | Prime ministers | Portrait | Term in office[332] | Lok Sabha | Constituency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | Tenure | |||||

| 1 | Jawaharlal Nehru |

|

15 August 1947 | 27 May 1964 | 16 years, 286 days | Constituent Assembly | |

| 1st | Phulpur | ||||||

| 2nd | |||||||

| 3rd | |||||||

| Acting | Gulzarilal Nanda |

|

27 May 1964 | 11 January 1966 | 13 days | Sabarkantha | |

| 2 | Lal Bahadur Shastri |

|

1 year, 216 days | Allahabad | |||

| Acting | Gulzarilal Nanda |

|

11 January 1966 | 24 January 1966 | 13 days | Sabarkantha | |

| 3 | Indira Gandhi |

|

24 January 1966 | 24 March 1977 | 15 years, 350 days | Rajya Sabha MP from Uttar Pradesh | |

| 4th | Rae Bareli | ||||||

| 5th | |||||||

| 14 January 1980 | 31 October 1984 | 7th | Medak | ||||

| 4 | Rajiv Gandhi |

|

31 October 1984 | 2 December 1989 | 5 years, 32 days | Amethi | |

| 8th | |||||||

| 5 | P. V. Narasimha Rao |

|

21 June 1991 | 16 May 1996 | 4 years, 330 days | 10th | Nandyal |

| 6 | Manmohan Singh |

|

22 May 2004 | 26 May 2014 | 10 years, 4 days | 14th | Rajya Sabha MP from Assam |

| 15th |

List of deputy prime ministers

| No. | Deputy PM | Portrait | Term in office | Lok Sabha | Constituency | Prime Minister | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | Tenure | ||||||

| 1 | Vallabhbhai Patel |

|

15 August 1947 | 15 December 1950 | 3 years, 4 months | Constituent Assembly | Jawaharlal Nehru | |

| 2 | Morarji Desai |

|

13 March 1967 | 16 July 1969 | 2 years, 128 days | 4th | Surat, Gujarat | Indira Gandhi |

See also

- Electoral history of the Indian National Congress

- Congress Working Committee

- All India Congress Committee

- Pradesh Congress Committee

- List of presidents of the Indian National Congress

- List of Indian National Congress breakaway parties

- Nehru–Gandhi family

- List of political parties in India

- List of chief ministers from the Indian National Congress

- List of state presidents of the Indian National Congress

- Politics of India

- High command culture

- United Progressive Alliance

References

Notes

- ^ «The first modern nationalist movement to arise in the non-European empire, and one that became an inspiration for many others, was the Indian Congress.»[35]

- ^ «South Asian parties include several of the oldest in the post-colonial world, foremost among them the 129-year-old Indian National Congress that led India to independence in 1947»[37]

- ^ «The organization that led India to independence, the Indian National Congress, was established in 1885.»[38]

- ^ [b][37][c][38]

- ^ «… anti-colonial movements … which, like many other nationalist movements elsewhere in the empire, were strongly influenced by the Indian National Congress.»[35]

- ^ The «R» stood for Requisition or Ruling

- ^ The «O» stands for organisation/Old Congress.

Citations

- ^ a b «Mallikarjun Kharge wins Congress Presidential elections, set to become first non-Gandhi head of party in 24 years — The Economic Times». Economictimes.indiatimes.com. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ a b Phukan, Sandeep (19 October 2022). «Mallikarjun Kharge wins Congress presidential election with over 7,800 votes». The Hindu.

- ^ «Sonia Gandhi to chair Congress parliamentary strategy group meeting to formulate strategy for Winter Session of Parliament». ThePrint. 29 November 2022.

- ^

- «Indian National Congress: From 1885 till 2017, a brief history of past presidents». Kanishka Singh. The Indian Express. 5 December 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- «Sagely leader: Dadabhai Naoroji». Praveen Davar. Telegraph India. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- «AO Hume, ‘Father’ of Indian National Congress who was distrusted by the British & Indians». DEEKSHA BHARDWAJ. ThePrint. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Sinha, Arunav (28 December 2015). «Cong founder was district collector of Etawah». The Times of India. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Sir William Wedderburn (2002). Allan Octavian Hume: Father of the Indian National Congress, 1829–1912 : a Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-565287-1.

- Kanta Kataria (2013). «A.o. Hume: His Life and Contribution to the Regeneration of India». The Indian Journal of Political Science. 74 (2): 245–252. JSTOR 24701107.

- ^ «Rent relief unlikely for Congress’s Delhi properties». The Times of India. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ «Kisan and Khet Mazdoor Congress sets 10-day deadline for Centre to concede demands». The Hindu. The Hindu Group. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ «Southern states ahead in Congress membership drive, Telangana unit leads». ThePrint. 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Congress’ Digital Membership Drive Gains Focus With Boost In Participation, South Contributes Significantly». ABP News. 27 March 2022.

- ^ Emiliano Bosio; Yusef Waghid, eds. (31 October 2022). Global Citizenship Education in the Global South: Educators’ Perceptions and Practices. Brill. p. 270. ISBN 9789004521742.

- ^ a b DeSouza, Peter Ronald (2006). India’s Political Parties Readings in Indian Government and Politics series. SAGE Publishing. p. 420. ISBN 978-9-352-80534-1.

- ^ a b Rosow, Stephen J.; George, Jim (2014). Globalization and Democracy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 91–96. ISBN 978-1-442-21810-9.

- ^ [9][10][11]

- ^ a b N. S. Gehlot (1991). The Congress Party in India: Policies, Culture, Performance. Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 150–200. ISBN 978-81-7100-306-8.

- ^ a b c Soper, J. Christopher; Fetzer, Joel S. (2018). Religion and Nationalism in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–210. ISBN 978-1-107-18943-0.

- ^ [10][11][13][14]

- ^ a b c d Lowell Barrington (2009). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices. Cengage Learning. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-618-49319-7.

- ^ Agrawal, S. P.; Aggarwal, J. C., eds. (1989). Nehru on Social Issues. New Delhi: Concept Publishing. ISBN 978-817022207-1.

- ^ [16][17]

- ^ Meyer, Karl Ernest; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2012). Pax Ethnica: Where and How Diversity Succeeds. PublicAffairs. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-61039-048-4. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ [16][19]

- ^ a b c «Political Parties – NCERT» (PDF). National Council of Educational Research and Training. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Cabestan, Jacques deLisle, ed. (2013). Inside India Today (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-04823-5.

… were either guarded in their criticism of the ruling party — the centrist Indian National Congress — or attacked it almost invariably from a rightist position. This was so for political and commercial reasons, which are explained, …

- ^ [21][22][16]

- ^ Wu, Jin; Gettleman, Jeffrey (22 May 2019). «India Election 2019: A Simple Guide to the World’s Largest Vote». The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

The Indian National Congress led India for most of the nation’s post-independence history. This secular, center-left party’s leader is Rahul Gandhi, whose father, grandmother and great-grandfather were prime ministers.

- ^ S. Harikrishnan, ed. (2022). Social Spaces and the Public Sphere: A Spatial-history of Modernity in Kerala. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000786583.

Electorally, both the left-leaning Communist parties (and allies) and the centre-left Indian National Congress (and allies) have been active in Kerala.

- ^ Shekh Moinuddin, ed. (2021). Digital Shutdowns and Social Media: Spatiality, Political Economy and Internet Shutdowns in India. Springer Nature. p. 99. ISBN 9783030678883.

Meanwhile, in the last four years, there has been a shift in social content and strategy of the BJP and the major opposition party, centre-left Indian National Congress (INC).

- ^ [24][25][26]

- ^ «Progressive Alliance Participants». Progressive Alliance. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ «Full Member Parties of Socialist International». Socialist International.

- ^ «India General (Lok Sabha) Election 2014 Results». mapsofindia.com.

- ^ «Election Results India, General Elections Results, Lok Sabha Polls Results India – IBNLive». in.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015.

- ^ «List of Political Parties and Election Symbols main Notification Dated 18.01.2013» (PDF). India: Election Commission of India. 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ a b «Party Position in the Rajya Sabha» (PDF). Rajya Sabha. Retrieved 14 July 2018.