Ровно 65 лет назад, 14 мая 1955 года, в Варшаве восемь государств «социалистической ориентации» во главе с СССР подписали Договор о дружбе и сотрудничестве, давший старт одному из самых известных военных союзов в истории. «Известия» вспоминают историю Варшавского договора.

Когда маски сорваны

Блок НАТО, объединивший поначалу 12 стран при очевидной гегемонии США, был основан 4 апреля 1949 года. В Советском Союзе с ответным созданием военного союза не торопились. Считалось, что вполне достаточно партийной вертикали, которой подчинялись лидеры стран советского блока, а значит, и их армии. А в Польше и ГДР надеялись на более веские основания для совместных боевых действий в случае наступления часа икс.

На пропагандистском поле Москва отвечала порой самыми неожиданными способами. В марте 1954 года Советский Союз даже подал заявку на вступление в НАТО. «Организация Североатлантического договора перестала бы быть замкнутой военной группировкой государств, была бы открыта для присоединения других европейских стран, что наряду с созданием эффективной системы коллективной безопасности в Европе имело бы важнейшее значение для укрепления всеобщего мира», — говорилось в документе.

Предложение было отвергнуто на том основании, что членство СССР противоречило бы демократическим и оборонительным целям альянса. В ответ Советский Союз принялся обвинять Запад в агрессивных планах. «Маски сорваны» — такова была реакция Москвы, прогнозируемо оставшейся перед закрытыми дверями НАТО.

Подписание Североатлантического договора, Вашингтон, 1949 год

Фото: ТАСС/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Предвестием военного блока «стран социализма» считается совещание генеральных секретарей компартий и военного руководства стран коммунистической ориентации, состоявшееся в Москве еще при Иосифе Сталине, в январе 1951 года. Именно там начальник штаба Группы советских войск в Германии генерал армии Сергей Штеменко заговорил о необходимости создания военного союза братских социалистических стран — для прямого противостояния НАТО.

СССР к тому времени уже взял на вооружение гуманитарный арсенал «борьбы за мир». Но чем миролюбивее была риторика Москвы, тем сильнее боялись «советской угрозы» «на том берегу». Появился даже популярный анекдот: Сталин (в более поздних вариантах — Хрущев и Брежнев) объявляет: «Войны не будет. Но будет такая борьба за мир, что камня на камне не останется». Обе стороны убеждали мир в агрессивности противника.

Германская угроза

Конечно, Штеменко был не единственным «ястребом», ратовавшим за создание общего военного «кулака» стран социализма. Авторитет Советской армии в то время был чрезвычайно высок. Народы, пострадавшие от нацизма, хорошо знали, кто и как сломил ему хребет. Тем более что у власти в социалистических странах оказались недавние подпольщики, антифашисты, которые были обязаны Москве своим спасением. Многие хотели примкнуть к этой силе. И политики, и генералы государств Восточной Европы надеялись как на советское вооружение, так и на более тесное сотрудничество армий. Лучшей академии они для себя не представляли.

Инициаторами военного союза были прежде всего представители Польши, Чехословакии и ГДР. У них был повод опасаться «угрозы из Бонна». США не выдержали своего первоначального плана оставить Западную Германию демилитаризованной. В 1955 году ФРГ стала членом НАТО. Этот шаг вызвал возмущение в советском лагере. Карикатуры на «боннских марионеток» ежедневно публиковались во всех советских газетах.

Пехота ГДР и танки ЧССР и ГДР. Совместные учения объединенных вооруженных сил государств – участников Варшавского договора «Влтава-66», 1966 год

Фото: РИА Новости/В. Гжельский

Непосредственные соседи ФРГ всё еще опасались «нового Гитлера». А в ГДР не без оснований считали, что ФРГ при поддержке НАТО может рано или поздно поглотить Восточную Германию. Лозунги о «единой Германии» были весьма популярны в Бонне. Румынию и Албанию беспокоила схожая ситуация, сложившаяся в Италии. Ее тоже постепенно вооружали натовцы.

После смерти Сталина СССР несколько умерил наступательный порыв по всем фронтам — и армейским, и идеологическим. Утихла война в Корее. Гораздо агрессивнее с середине 1953 года держались наши бывшие союзники по антигитлеровской коалиции, британцы и американцы. Тем из них, кто преувеличенно относится к «роли личности в истории», показалось, что после смерти Сталина Советский Союз можно если не «помножить на ноль», то заметно потеснить в международной политике. Но ни Хрущев, ни его коллеги по президиуму капитулировать не намеревались.

Варшавский ужин

В Варшаве в мае 1955 года открылось Совещание европейских государств по обеспечению мира и безопасности в Европе. Основные детали Договора к тому времени уже были проработаны. Социалистические страны Восточной Европы подписали Договор о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи. По существу — военный союз, чаще всего именуемый Организацией (в противовес «вражескому» альянсу) Варшавского договора (сокращенно — ОВД).

Первой Договор, в соответствии с алфавитным порядком, подписала Албания. Затем — Болгария, Венгрия, ГДР, Польша, Румыния, СССР и Чехословакия. К ужину всё было готово. В тексте Договора, как и в принятой через несколько лет военной доктрине, отмечалось, что ОВД имеет сугубо оборонительный характер. Но оборонительный характер доктрины не означал пассивности. В боевом планировании допускалась возможность упреждающего удара против группировок войск вероятного противника, «изготовившихся к нападению».

Председатель Совета министров СССР Николай Булганин (в центре) в присутствии членов советской делегации и делегаций других стран подписывает Договор о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи между Албанией, Болгарией, Венгрией, ГДР, Польшей, Румынией, CCCР, Чехословакией на Варшавском совещании, 14 мая 1955 года

Фото: РИА Новости

Неспроста для столь важного совещания и — без преувеличений — исторического акта Хрущев и его соратники выбрали Варшаву. Во-первых, не стоило лишний раз подчеркивать гегемонию СССР. Во-вторых, Варшава располагалась ближе к другим дружественным столицам — Берлину, Будапешту, Праге… В-третьих, поляки сильнее других народов Восточной Европы пострадали от немцев и нуждались в гарантиях безопасности… А участники Договора, разумеется, обязывались всеми средствами помогать любой из стран ОВД в случае военной агрессии.

На страже мира и социализма

Главнокомандующим Объединенными вооруженными силами стран – участниц Варшавского договора стал советский маршал Иван Конев. Штаб возглавил генерал армии Алексей Антонов — член Ставки Верховного главнокомандующего в годы войны. На Вашингтон назначение Конева — одного из маршалов Победы — произвело сильное впечатление. Американский военный историк полковник Майкл Ли Лэннинг в своей книге «Сто великих полководцев» писал, что роль Конева во главе вооруженных сил Варшавского договора куда важнее роли Георгия Жукова на посту министра обороны СССР.

Коневу и Антонову, возглавлявшим дружественные армии целую пятилетку, действительно удалось многое. Они превратили ОВД в эффективную военную силу. Достаточно вспомнить Единую систему противовоздушной обороны ОВД, которая централизованно управлялась и объединяла все силы ПВО.

Иван Конев

Фото: РИА Новости/Юрий Абрамочкин

Тогда, в 1955-м, для Запада ситуация стала наглядной: ФРГ, Франция, да и Великобритания оказались заложниками хрупкого мира между двумя сверхдержавами — СССР и США. После Варшавского договора биполярный мир, уже ставший реальностью де-факто, стал таковой де-юре. Во многом это помогало Советскому Союзу налаживать отношения с Парижем и Бонном, что в 1970-е вылилось в «эпоху разрядки».

Противостояние систем

Американская военная доктрина никогда не была даже внешне миролюбивой, допуская применение упреждающего ядерного удара. Но страх ответного удара оставался главным сдерживающим фактором. А вторым тормозом для американской экспансии была Организация Варшавского договора.

Чем-то ОВД напоминала Священный Союз, организованный монархами — победителями Наполеона. Тогда Россия, действуя по всей Восточной Европе, пресекала попытки революционных волнений. Для «дружественных армий» самые суровые испытания тоже были связаны с желанием политической власти сохранить существующее положение вещей, пресекая контрреволюцию. Так было во время самых известных военных операций ОВД — в 1956 году в Венгрии и в 1968 году в Чехословакии.

Но политическая ответственность, как известно, лежит не на военном командовании. СССР, как и Российскую империю в годы Священного Союза, недруги стали называть жандармом Европы.

Ввод войск ОВД в Прагу, 1968 год

Фото: РИА Новости/Юрий Абрамочкин

В то же время в СССР к вопросам расширения влияния ОВД относились с чувством меры. В 1968 году из организации вышла Албания. В разные годы можно было бы превратить организацию в межконтинентальную. И КНР (до поры до времени), и Вьетнам, и Куба, и Никарагуа, и еще ряд государств проявляли стремление присоединиться к Договору. Но Организация осталась сугубо европейской.

В том же 1968 году проявился особый статус Румынии: эта страна не подчинилась решению большинства и не приняла участия в операции «Дунай». И все-таки капризный Бухарест остался в ОВД. Румынских коммунистов устраивала роль enfant terrible социалистического лагеря.

Развалины блока

Срок действия Договора истек 26 апреля 1985 года. К тому времени в составе армий ОВД насчитывалось почти 8 млн военнослужащих. Тогда еще никто не мог предсказать, что генеральный секретарь ЦК КПСС Михаил Горбачев, месяц назад сменивший умершего Константина Черненко, станет последним советским вождем. Продление Договора казалось (и было) делом техники. Его и продлили — на 20 лет, с соблюдением всех юридических тонкостей.

Но через несколько лет история ускорила свой бег. В 1989 году социалистические режимы Восточной Европы начали рассыпаться, как детские крепости из песка. ОВД всё еще существовала — и военные относились к ней вполне серьезно. Они, к счастью, не стали действовать торопливо и суматошно и после 1990 года, когда «мир социализма» перестал существовать. 25 февраля 1991 года государства – участники ОВД упразднили ее военные структуры, но мирные направления Договора сохранили в неприкосновенности.

Генеральный секретарь ЦК КПСС Михаил Горбачев и член Политбюро ЦК КПСС Александр Яковлев (справа) во время встречи руководителей государств – участников Варшавского договора, 1989 год

Фото: РИА Новости/Борис Бабанов

Только через полгода после распада Советского Союза, 1 июля 1991 года, все государства, входившие в ОВД, и их правопреемники в Праге подписали Протокол о полном прекращении действия Договора. Почти все страны – участницы Варшавского договора ныне состоят в НАТО. Даже Албания.

Но Договор, существовавший 36 лет, сыграл в истории Европы роль, которую забывать не стоит. По крайней мере, для Старого Света это были мирные годы. Отчасти — благодаря ОВД.

Автор — заместитель главного редактора журнала «Историк»

Организация Варшавского договора создавалась народами, пережившими все ужасы немецкой тирании, во время, когда этим народам стала угрожать англосаксонская тирания, называемая последними демократией. Заключившие военный договор страны Восточной Европы, ГДР, СССР военным союзом стремились сохранить свое право на достойную жизнь.

При заключении договора армии Советского Союза и остальных стран, подписавших договор, были призваны оберегать мирную жизнь граждан, а не якобы навязанный странам Восточной Европы социалистический общественно-политический строй. Политическая социалистическая система объединяла, сплачивала народы, не позволяла захватить страны изнутри, повышала безопасность государств и боеспособность армий стран Варшавского договора, а не являлась самоцелью СССР.

Еще в 1930-х годах Иосиф Сталин со своими соратниками отвергли идею мировой революции, и обвинения СССР и его армии в навязывании другим странам социализма являются продуктом геополитических противников России. СССР не стремился к экспорту социализма, а поддерживал его только в том случае, если он обеспечивал безопасность государства, его народа.

Имеются сведения, что после войны Сталин отверг предложения поддержать коммунистов Греции и Италии в установлении в этих странах социалистического строя. Он сказал примерно следующее: «Америка богатая, Америка очень богатая страна, и она никогда не смирится с тем, что Греция и Италия станут социалистическими. А наш народ устал от войны».

А вот США пролили много крови народов других стран, навязывая им демократию. Например, итальянских коммунистов нейтрализовали подготовленные ЦРУ бандиты. В Италии этих бандитов назвали итальянской мафией. Но мафия это была не итальянская, а американская, созданная, как правило, из этнических итальянцев.

Необходимо отметить, что после окончания войны союзники США в Западной Европе постоянно увеличивали численность и оснащенность своих вооруженных сил. В период с 1949 по 1952 год военные бюджеты этих стран были удвоены, а срок службы в армии увеличен, производство вооружений возросло. Образованный в 1949 году блок НАТО представлял прямую угрозу для стран Восточной Европы и СССР.

Растущее военное присутствие США в Европе вынуждало к принятию соответствующих мер обеспечения безопасности стран, не подчинившихся Америке. Тем более что США начали нарушать принятые ранее договоренности. Вместо того чтобы превращать Германию в демилитаризованную зону, они приняли Федеративную Республику Германию в НАТО.

Фактически США заключили военный союз с Западной Германией и другими странами Западной Европы. Союз этот был направлен против СССР и дружественных ему стран.

Сталин не стал создавать военный блок, аналогичный НАТО, а организовал подписание со странами Восточной Европы, включая ГДР, соглашения. Подписанное в 1951 году соглашение обязывало союзников СССР передать свои армии под непосредственное советское командование в случае войны. Был создан специальный комитет для обеспечения союзных армий необходимым военным снаряжением и производства в этих странах продукции оборонного значения. Председателем военно-координационного комитета первоначально был избран Николай Булганин, а вскоре на это место выбрали лучшего маршала Вооруженных Сил СССР Александра Василевского.

Организация Варшавского договора была создана уже после смерти Сталина. На Варшавском совещании европейских государств по обеспечению мира и безопасности в Европе 14 мая 1955 года Албанией, Болгарией, Венгрией, ГДР, Польшей, Румынией, Чехословакией и Советским Союзом был подписан Варшавский договор. Договор вступил в силу 5 июня 1955 года. Он назывался договором о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи. Военный союз восьми социалистических государств, сложившийся на основе Варшавского договора, получил название Организация Варшавского договора (ОВД). Договор был заключен на принципах полного равенства его участников. Он являлся добровольным союзом государств. Для руководства блоком был создан Политический консультативный комитет (ПКК).

Варшавский договор носил исключительно оборонительный характер и полностью отличался от агрессивных блоков. ОВД была создана спустя шесть лет после возникновения НАТО. Она создавалась с целью противодействия усилению опасности развязывания новой мировой войны, так как в результате Второй мировой войны США не достигли всех поставленных целей, а именно не подчинили себе всю Европу, Китай и Корею. СССР под руководством Сталина не допустил полного господства США в Европе и Юго-Восточной Азии, чем сохранил свободу и независимость народов, проживавших на территории Советского Союза.

Восьми странам, входящим в ОВД, противостояли 12 стран, входивших в НАТО, в том числе такие крупные державы как США, Англия, ФРГ и Франция. К 1991 году в НАТО уже было 16 стран, а в ОВД – семь стран. Надо отметить, что, хотя Китай и не входил в ОВД, в 1955 году он присутствовал при подписании договора в качестве наблюдателя и союзника СССР. Но и без Китая паритет ОВД и НАТО был создан и поддерживался несколько десятилетий. Надо отдать должное великому советскому народу и народам Восточной Европы, сумевшим на равных противостоять НАТО. И, конечно, главная заслуга в сохранении мира в Европе принадлежит СССР, который обеспечил послевоенную безопасность, несмотря на потерю людей, страшные разрушения и расходование огромных денежных средств на ведение военных действий во время войны 1941–1945 годов и восстановление народного хозяйства после войны.

О силе и возможностях вооруженных сил ОВД говорят хотя бы проводимые ими учения. Ю. Первов пишет, что в последний период существования Варшавского договора было проведено КШУ под кодовым названием «Гранит». Только на одном из стратегических направлений в течение двух-трех суток осуществлялось до 2500–3000 самолетовылетов, не говоря уже о большом количестве привлекаемых наземных и морских сил ПВО. И хотя учения проводились в достаточно сложных условиях, надо отдать должное как ВВС СССР, так и ВВС стран Варшавского договора: не было ни летных происшествий, ни даже предпосылок к ним.

С приходом к власти в СССР Михаила Горбачева Организация Варшавского договора начала стремительно разрушаться. С началом правления Горбачева советское руководство не только перестало препятствовать, а стало поощрять проведение США «цветных революций» в восточноевропейских государствах. Особенно активно эти революции проводились в 1989–1990 годах. В 1989 году пала Берлинская стена, а год спустя две Германии были объединены в единое государство. Для Союза это означало потерю верного союзника. Первого июля 1991 года Организация Варшавского договора была ликвидирована.

После роспуска Организации Варшавского договора Североатлантический альянс стал превосходить СССР по танкам и артиллерии в 1,5 раза, по самолетам и вертолетам – в 1,3 раза. В результате распада Советского Союза превосходство НАТО над Россией по танкам и артиллерии увеличилось в три раза, по БТР – в 2,7 раза. НАТО не прекратил своего существования одновременно с ОВД, а принял в свои ряды все страны, которые входили в Организацию Варшавского договора, и всю Европу нацелил на СССР. Россия потеряла союзников в Европе и значительно уменьшила уровень своей безопасности, прежде всего из-за, мягко говоря, недальновидной политики Горбачева и Шеварднадзе. Последний, сдавая США ГДР, отказался от сотен миллиардов марок, говоря госсекретарю США Джеймсу Бейкеру: «Мы с друзьями не торгуемся!».

Леонид Масловский

65 лет назад руководители стран соцлагеря создали Организацию Варшавского договора (ОВД), которая объединила СССР и восточноевропейские государства в оборонительный союз. Его появление стало ответом на образование в 1949 году Североатлантического альянса. ОВД открыла широкие возможности для военного взаимодействия государств соцблока. Как полагают эксперты, Варшавский договор позволил предотвратить развязывание глобального конфликта в эпоху холодной войны. После его краха в 1991 году, отмечают аналитики, мир стал однополярным, что негативно сказалось на международной безопасности.

14 мая 1955 года в столице социалистической Польши был подписан Договор о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи. Его участниками стали СССР, Польша, Чехословакия, Венгрия, ГДР, Болгария, Румыния и Албания. Документ предусматривал оказание военной помощи в случае нападения на одну из сторон.

Военный союз получил название Организации Варшавского договора (ОВД). В её рамках государства социалистического лагеря учредили Политический консультативный комитет (ПКК), Объединённое командование вооружёнными силами (ОКВС) и различные вспомогательные органы. Договор был заключён на 20 лет с автоматической пролонгацией на десять лет. В 1985 году он был продлён ещё на 20 лет.

Создание системы коллективной самообороны СССР и восточноевропейских государств стало ответной мерой на появление Североатлантического альянса в 1949 году. Данные блоки стали символами биполярной системы международных отношений, характеризовавшейся идеологическим противостоянием и холодной войной.

Также по теме

«Американцы просто разыгрывают польскую карту»: что стоит за заявлениями о возможном выводе войск США из Германии

Пентагон рассматривает возможность полного или частичного вывода своих войск с территории Германии. Как сообщает The Washington Post,…

В разговоре с RT руководитель Бюро военно-политического анализа Александр Михайлов назвал образование ОВД закономерным процессом. По его мнению, деятельность Организации Варшавского договора была направлена на то, чтобы уравновесить баланс сил между Западом и Востоком.

«После победы над фашизмом СССР и США фактически поделили Европу на зоны влияния. Это была реальность того времени, и вряд ли с учётом имеющихся противоречий она могла быть иной. Вашингтон объединил лояльные ему государства в рамках НАТО, Москва — в виде Варшавского договора», — констатировал Михайлов.

В беседе с RT директор Центра военно-политических исследований МГИМО Алексей Подберёзкин заявил, что деятельность Организации Варшавского договора позволила предотвратить развязывание нового глобального вооружённого конфликта.

«ОВД являлась сугубо оборонительным союзом. Члены организации не собирались ни на кого нападать — объединение усилий требовалось для эффективного сдерживания НАТО, которое появилось почти на шесть лет раньше. С точки зрения глобальной безопасности существование Варшавского договора было гарантом мира, так как Запад понимал, с каким серьёзным противником ему придётся иметь дело», — пояснил Подберёзкин.

Архитектура безопасности

Варшавский договор стал правовой основой для интенсивного военного сотрудничества подписавших его государств. Советский Союз активно перевооружал армии восточноевропейских государств на современную технику и стимулировал развитие национальной оборонной промышленности. В материалах Минобороны РФ говорится, что огромную роль в этом процессе сыграл министр обороны СССР (1976—1984) маршал Дмитрий Устинов.

Армии восточноевропейских стран и советские войска регулярно проводили совместные учения, в том числе крупномасштабные. Например, участниками оперативно-стратегических манёвров «Запад-81» стали не менее 100 тыс. человек.

- Работа реактивной артиллерии на учениях «Запад-81»

- РИА Новости

- © В. Киселев

Также одними из крупнейших учений ОВД с применением ракетного оружия считается «Щит-82». На Западе их называли «семичасовая ядерная война» из-за того, что 18 июня 1982 года между 06:00 и 13:00 мск СССР осуществил десятки ракетных пусков с наземных, морских и воздушных носителей.

Важный вклад в совершенствование взаимодействия армий Организации Варшавского договора внёс начальник Генштаба ВС СССР (1977—1984) Николай Огарков. Так, на манёврах «Запад-81» впервые была использована автоматизированная система управления войсками.

«Советский Союз вложил в эту организацию огромное количество ресурсов, по сути, выстроил всю архитектуру безопасности. Многие офицеры, в том числе высокопоставленные, проходили обучение в Москве, в том числе в Академии Генштаба. Таким образом СССР формировал лояльную военную элиту в странах соцлагеря и заодно подтягивал уровень её профессионализма», — отметил Михайлов.

Однако отношения государств в рамках ОВД не были безоблачными. Первый серьёзный кризис внутри блока произошёл уже в 1956 году, когда в Венгрии вспыхнуло антиправительственное восстание. Первоначально советское правительство не собиралось применять силу и даже постановило вывести из республики войска.

Но в конце октября первый секретарь ЦК КПСС Никита Хрущёв распорядился провести операцию по смещению венгерского лидера Имре Надя. В начале ноября 30-тысячная советская группировка под командованием маршала Георгия Жукова вошла в Будапешт по приглашению созданного Яношем Кадаром правительства и рассеяла силы восставших. Основная часть венгерской армии при этом сохраняла нейтралитет.

Ещё одним тревожным событием стала знаменитая «Пражская весна». 18 августа 1968 года после длительных переговоров с главой ЦК Коммунистической партии Чехословакии Александром Дубчеком руководители СССР, Польши, Венгрии, ГДР и Болгарии приняли решение о вводе в Чехословакию контингента ОВД. Чехословацкие вооружённые силы не вмешивались в ситуацию, и антикоммунистические протесты были подавлены.

Оба события, как отмечают эксперты, теперь используются в качестве повода для разжигания русофобии и борьбы с памятью о победе Советского Союза над гитлеровской Германией.

«Сейчас очень легко обвинять во всём Москву, но в реальности ситуация была намного сложнее. Одной из причин обоих восстаний стало то обстоятельство, что в годы Второй мировой войны Венгрия была союзником Германии, а Чехословакия — протекторатом Берлина. После войны в этих странах сохранились антисоветские силы, которые поддерживались Западом. Впрочем, в СССР руководствовались лозунгом о «дружбе народов», поэтому говорить об этом было не принято», — пояснил Алексей Подберёзкин.

Нарушенный баланс

Эксперты обратили внимание на то, что СССР часто упрекают в якобы господствующем положении в рамках ОВД. Данное утверждение зачастую обосновывается тем, что Объединённое командование вооружёнными силами располагалось в Москве, а его начальниками становились исключительно советские военные деятели.

Впрочем, как полагает Михайлов, Москва не имела возможности осуществлять тотальный контроль над восточноевропейскими республиками. Например, в 1968 году Албания покинула ОВД.

Самостоятельную политику проводила Румыния. Бухарест осудил ввод войск в Чехословакию, не поддержал афганскую кампанию СССР и сотрудничал с ФРГ и Пакистаном в сфере создания ядерного оружия. Кроме того, республика пользовалась кредитами МВФ и вкрапляла в номинально социалистическую идеологию элементы национализма.

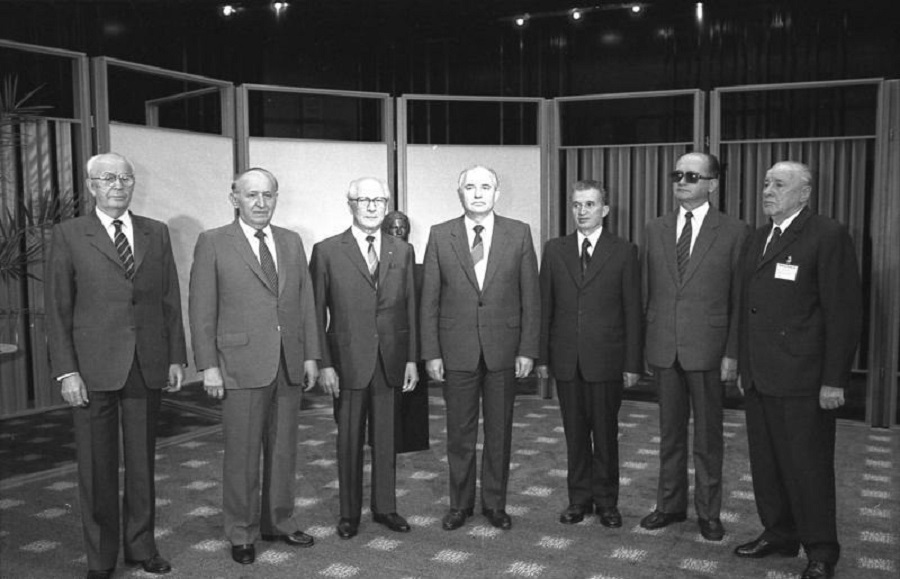

- Руководители государств — членов ОВД на заседании Политического консультативного комитета (ПКК)

- © Wikimedia commons / Bundesarchiv, Bild

«Страны соцлагеря отличались друг от друга и на самом деле имели большую автономию от Москвы. Факторов, которые влияли на отношения с СССР, было очень много, в том числе экономических. И с крахом социалистических режимов судьба ОВД была предрешена», — рассуждает Михайлов.

В феврале 1991 года страны — участницы Варшавского договора решили распустить военные структуры организации. 1 июля того же года представители этих государств подписали протокол о полном прекращении действия Договора о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи.

Как отметил Алексей Подберёзкин, после ликвидации ОВД в мире воцарилась однополярная система международных отношений, которая характеризуется доминантой одного военного блока. Прямыми последствиями разрушения прежнего баланса сил эксперт назвал вмешательство НАТО в Боснийский кризис 1992—1995 годов и агрессию альянса в Югославии в 1999 году.

Также по теме

Неизменные приоритеты: почему НАТО продолжит заниматься «сдерживанием» России даже в условиях пандемии коронавируса

Североатлантический альянс будет придерживаться политики «сдерживания» России даже во время пандемии коронавируса, заявил генсек НАТО…

«Югославская государственность стала первой жертвой военного вторжения альянса, но эта агрессия была бы невозможной при существовании ОВД. С разрушением Организации Варшавского договора пропал естественный противовес НАТО, а западный блок решил, что может безнаказанно вмешиваться в дела суверенных государств», — сказал Подберёзкин.

Однако с ликвидацией ОВД в мире не исчезла потребность в международной структуре, которая смогла бы обеспечивать равновесный баланс сил, отметил в комментарии RT эксперт Ассоциации военных политологов Андрей Кошкин.

«Основными причинами крушения ОВД стали кризис советской государственности и желание руководства СССР того времени положить конец холодной войне. Однако Запад воспользовался ослаблением Москвы, чтобы взять под свой контроль Восточную Европу. В 2000-е годы Россия начала объединять усилия с соседями в рамках ОДКБ и ШОС. Эти организации нельзя назвать заменой ОВД, но их существование свидетельствует о том, что однополярная система постепенно уходит в прошлое», — подчеркнул Кошкин.

Кроме того, как отметили эксперты, ещё одним последствием крушения ОВД стало расширение НАТО на восток. Этот процесс происходил вопреки данным Москве обещаниям официальных лиц США и альянса. В результате включения в западный блок бывших участников Варшавского договора, а также прибалтийских республик ситуация на западной границе России заметно ухудшилась.

По мнению Михайлова, с первых дней своего существования Североатлантический альянс представлял серьёзную угрозу безопасности СССР. В случае гипотетического конфликта с ним существование ОВД позволяло встретить агрессора на дальних подступах, пояснил он.

«С крахом Варшавского договора и расширением НАТО на восток этот буфер исчез. В итоге мы видим, как в последние годы альянс наращивает напряжение на наших западных рубежах. Хотя современная Россия, конечно же, обладает эффективными средствами сдерживания НАТО, которые отрезвляют западных стратегов», — констатировал аналитик.

Варшавский договор: из истории создания

В XX веке европейский континент не единожды делился на крупные военные альянсы. И даже после победы над нацистской Германией, когда полмира встало под ружье против общего агрессора, было очевидно, что страны вскоре опять разобьются на два враждующих лагеря. Так и произошло.

В апреле 1949 года десять европейских стран совместно с Канадой и США подписали Североатлантический договор. Появилось всем известное НАТО. Главной целью альянса явилось противостояние «советской угрозе».

В 1955 году к НАТО присоединилась ФРГ. Это событие стало «спусковым крючком» для Никиты Сергеевича Хрущева, который начал активно форсировать процесс по созданию военного блока для противостояния западным державам. 14 мая этого же года в польской столице лидеры восьми государств подписали Варшавский договор. Под эгидой Советского Союза объединились Восточная Германия, Польша, Болгария, Румыния, Венгрия, Чехословакия и Албания. Согласно условиям договора, страны-участницы обязывались оказывать всю необходимую помощь друг другу, в том числе и военную, в случае нападения на одну из них.

Стоит ли говорить, что Варшавский договор, как и договор между членами Североатлантического альянса, декларировал исключительно мирные цели? «Договаривающиеся Стороны обязуются в соответствии с Уставом Организации Объединенных Наций воздерживаться в своих международных отношениях от угрозы силой или ее применения и разрешать свои международные споры мирными средствами таким образом, чтобы не ставить под угрозу международный мир и безопасность», — гласила первая статья.

Договор предусматривал формирование объединенных вооруженных сил. Первым командующим стал советский маршал Иван Степанович Конев. Штаб ОВД находился в Москве. Языком командования был русский. На нем готовилась вся основная документация организации.

С подписанием Варшавского договора СССР мог официально разместись свои войска на территории восточноевропейских государств. До этого советская армия формально могла находиться только на территории Германии.

Деятельность ОВД: эволюция и распад

Спустя год после подписания договора объединенными вооруженными силами была проведена первая операция. В Венгрии началось антисоветское восстание. Войска ОВД, в подавляющем большинстве из Советского Союза, в октябре — ноябре вели боевые действия с повстанцами, преимущественно в Будапеште. За две недели свыше двух с половиной тысяч мятежников были убиты, просоветский политический режим восстановлен. Бунтовщики неоднократно обращались за помощью к Соединенным Штатам и странам НАТО, но военной поддержки не получили, хотя через территорию Австрии поставлялись боеприпасы.

Восточная Европа стала плацдармом нового военного блока, где СССР, несомненно, играл первую скрипку. Подтверждением этому служат и 1961 год, Берлинский кризис, когда западная часть Берлина оказалась фактически в осаде, и мир чуть было не познакомился с реалиями ядерной войны; и 1968 год, когда полмиллиона военнослужащих вошли в Чехословакию для подавления «Пражской весны» и удержания страны от «ухода» на запад.

В общей сложности Организация Варшавского договора просуществовала тридцать шесть лет. Первой выйти из альянса захотела Албания. В 1962 году она приостановила свое участие в договоре, а после ввода войск в Чехословакию и вовсе его разорвала.

Начавшаяся в 1980-х годах «перестройка» еще больше ускорила процесс. Михаил Сергеевич Горбачев публично заявил о праве народов на суверенитет, чем не преминули воспользоваться союзники по договору. Буквально за несколько лет в странах-участницах ОВД прошла серия «бархатных революций», где местные коммунистические партии потерпели фиаско. 1 июля 1991 года стал последним днем действия Договора о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи.

[image reference needed] |

|

The Warsaw Pact in 1990 |

|

| Abbreviation | WAPA, DDSV |

|---|---|

| Successor | Collective Security Treaty Organization |

| Founded | 14 May 1955 |

| Founded at | Warsaw, Poland |

| Dissolved | 1 July 1991 |

| Headquarters | Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

|

Membership |

|

|

Supreme commander |

|

|

Chief of combined staff |

|

| Affiliations | Council for Mutual Economic Assistance |

The Warsaw Pact (WP),[3] formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance,[4] was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republics of Central and Eastern Europe in May 1955, during the Cold War. The term «Warsaw Pact» commonly refers to both the treaty itself and its resultant defensive alliance, the Warsaw Treaty Organization[5] (WTO). The Warsaw Pact was the military and economy complement to the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), the regional economic organization for the Eastern Bloc states of Central and Eastern Europe.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Dominated by the Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact was established as a balance of power or counterweight to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Western Bloc.[15][16] There was no direct military confrontation between the two organizations; instead, the conflict was fought on an ideological basis and through proxy wars. Both NATO and the Warsaw Pact led to the expansion of military forces and their integration into the respective blocs.[16] The Warsaw Pact’s largest military engagement was the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, its own member state, in August 1968 (with the participation of all pact nations except Albania and Romania),[15] which, in part, resulted in Albania withdrawing from the pact less than one month later. The pact began to unravel with the spread of the Revolutions of 1989 through the Eastern Bloc, beginning with the Solidarity movement in Poland,[17] its electoral success in June 1989 and the Pan-European Picnic in August 1989.[18]

East Germany withdrew from the pact following German reunification in 1990. On 25 February 1991, at a meeting in Hungary, the pact was declared at an end by the defense and foreign ministers of the six remaining member states. The USSR itself was dissolved in December 1991, although most of the former Soviet republics formed the Collective Security Treaty Organization shortly thereafter. In the following 20 years, the Warsaw Pact countries outside the USSR each joined NATO (East Germany through its reunification with West Germany; and the Czech Republic and Slovakia as separate countries), as did the Baltic states which had been occupied and annexed by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II.

History[edit]

Beginnings[edit]

Conference during which the Pact was established and signed.

Before the creation of the Warsaw Pact, the Czechoslovak leadership, fearful of a rearmed Germany, sought to create a security pact with East Germany and Poland.[13] These states protested strongly against the re-militarization of West Germany.[19] The Warsaw Pact was put in place as a consequence of the rearming of West Germany inside NATO. Soviet leaders, like many European leaders on both sides of the Iron Curtain, feared Germany being once again a military power and a direct threat. The consequences of German militarism remained a fresh memory among the Soviets and Eastern Europeans.[7][8][20][21][22] As the Soviet Union already had an armed presence and political domination all over its eastern satellite states by 1955, the pact has been long considered «superfluous»,[23] and because of the rushed way in which it was conceived, NATO officials labeled it a «cardboard castle».[24]

The USSR, fearing the restoration of German militarism in West Germany, had suggested in 1954 that it join NATO, but this was rejected by the US.[25][26][27]

The Soviet request to join NATO arose in the aftermath of the Berlin Conference of January–February 1954. Soviet foreign minister Molotov made proposals to have Germany reunified[28] and elections for a pan-German government,[29] under conditions of withdrawal of the four powers’ armies and German neutrality,[30] but all were refused by the other foreign ministers, Dulles (USA), Eden (UK), and Bidault (France).[31] Proposals for the reunification of Germany were nothing new: earlier on 20 March 1952, talks about a German reunification, initiated by the so-called ‘Stalin Note’, ended after the United Kingdom, France, and the United States insisted that a unified Germany should not be neutral and should be free to join the European Defence Community (EDC) and rearm. James Dunn (USA), who met in Paris with Eden, Konrad Adenauer, and Robert Schuman (France), affirmed that «the object should be to avoid discussion with the Russians and to press on the European Defense Community».[32] According to John Gaddis, «there was little inclination in Western capitals to explore this offer» from the USSR,[33] while historian Rolf Steininger asserts that Adenauer’s conviction that «neutralization means sovietization», referring to the Soviet Union’s policies towards Finland known as finlandization, was the main factor in the rejection of the Soviet proposals.[34] Adenauer also feared that German unification might have resulted in the end of the CDU’s leading political role in the West German Bundestag.[35]

Consequently, Molotov, fearing that the EDC would be directed in the future against the USSR and «seeking to prevent the formation of groups of European States directed against the other European States»,[36] made a proposal for a General European Treaty on Collective Security in Europe «open to all European States without regard to their social systems»,[36] which would have included the unified Germany (thus rendering the EDC obsolete). But Eden, Dulles, and Bidault opposed the proposal.[37]

One month later, the proposed European Treaty was rejected not only by supporters of the EDC, but also by Western opponents of the European Defence Community (like French Gaullist leader Gaston Palewski) who perceived it as «unacceptable in its present form because it excludes the USA from participation in the collective security system in Europe».[38] The Soviets then decided to make a new proposal to the governments of the US, UK, and France to accept the participation of the US in the proposed General European Agreement.[38] As another argument deployed against the Soviet proposal was that it was perceived by Western powers as «directed against the North Atlantic Pact and its liquidation»,[38][39] the Soviets decided to declare their «readiness to examine jointly with other interested parties the question of the participation of the USSR in the North Atlantic bloc», specifying that «the admittance of the USA into the General European Agreement should not be conditional on the three Western powers agreeing to the USSR joining the North Atlantic Pact».[38]

A «Soviet Big Seven» threats poster, displaying the equipment of the militaries of the Warsaw Pact

Again, all proposals, including the request to join NATO, were rejected by the UK, US, and French governments shortly after.[27][40] Emblematic was the position of British General Hastings Ismay, a fierce supporter of NATO expansion. He opposed the request to join NATO made by the USSR in 1954[41] saying that «the Soviet request to join NATO is like an unrepentant burglar requesting to join the police force».[42]

In April 1954, Adenauer made his first visit to the United States, meeting Nixon, Eisenhower, and Dulles. Ratification of the EDC was delayed but the US representatives made it clear to Adenauer that the EDC would have to become a part of NATO.[43]

Memories of the Nazi occupation were still strong, and the rearmament of Germany was feared by France too.[8][44] On 30 August 1954, the French Parliament rejected the EDC, thus ensuring its failure[45] and blocking a major objective of US policy towards Europe: to associate West Germany militarily with the West.[46] The US Department of State started to elaborate alternatives: West Germany would be invited to join NATO or, in the case of French obstructionism, strategies to circumvent a French veto would be implemented in order to obtain German rearmament outside NATO.[47]

A typical Soviet military jeep UAZ-469, used by most countries of the Warsaw Pact

On 23 October 1954, the admission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the North Atlantic Pact was finally decided. The incorporation of West Germany into the organization on 9 May 1955 was described as «a decisive turning point in the history of our continent» by Halvard Lange, Foreign Affairs Minister of Norway at the time.[48] In November 1954, the USSR requested a new European Security Treaty,[49] in order to make a final attempt to not have a remilitarized West Germany potentially opposed to the Soviet Union, with no success.

On 14 May 1955, the USSR and seven other Eastern European countries «reaffirming their desire for the establishment of a system of European collective security based on the participation of all European states irrespective of their social and political systems»[50] established the Warsaw Pact in response to the integration of the Federal Republic of Germany into NATO,[7][9] declaring that: «a remilitarized Western Germany and the integration of the latter in the North-Atlantic bloc […] increase the danger of another war and constitutes a threat to the national security of the peaceable states; […] in these circumstances the peaceable European states must take the necessary measures to safeguard their security».[50]

One of the founding members, East Germany, was allowed to re-arm by the Soviet Union and the National People’s Army was established as the armed forces of the country to counter the rearmament of West Germany.[51]

The USSR concentrated on its own recovery, seizing and transferring most of Germany’s industrial plants, and it exacted war reparations from East Germany, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria using Soviet-dominated joint enterprises. It also instituted trading arrangements deliberately designed to favour the country. Moscow controlled the Communist parties that ruled the satellite states, and they followed orders from the Kremlin. Historian Mark Kramer concludes: «The net outflow of resources from eastern Europe to the Soviet Union was approximately $15 billion to $20 billion in the first decade after World War II, an amount roughly equal to the total aid provided by the United States to western Europe under the Marshall Plan.»[52]

In November 1956, Soviet forces invaded Hungary, a Warsaw Pact member state, and violently put down the Hungarian Revolution. After that, the USSR made bilateral 20-year-treaties with Poland (17 December 1956),[53] the GDR (12 March 1957),[54] Romania (15 April 1957; Soviet forces were later removed as part of Romania’s de-satellization),[55] and Hungary (27 May 1957),[56] ensuring that Soviet troops were deployed in these countries.

Members[edit]

The founding signatories of the Pact consisted of the following communist governments:

Observers[edit]

Mongolia: In July 1963, the Mongolian People’s Republic asked to join the Warsaw Pact under Article 9 of the treaty.[63] Due to the emerging Sino-Soviet split, Mongolia remained in an observer status.[63] In what was the first instance of a Soviet initiative being blocked by a non-Soviet member of the Warsaw Pact, Romania blocked Mongolia’s accession to the Warsaw Pact.[64][65] The Soviet government agreed to station troops in Mongolia in 1966.[66]

At first, China, North Korea, and North Vietnam had observer status,[67] but China withdrew in 1961 as a consequence of the Albanian-Soviet split, in which China backed Albania against the USSR as part of the larger Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960s.[68]

During the Cold War[edit]

For 36 years, NATO and the Warsaw Pact never directly waged war against each other in Europe; the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies implemented strategic policies aimed at the containment of each other in Europe, while working and fighting for influence within the wider Cold War on the international stage. These included the Korean War, Vietnam War, Bay of Pigs invasion, Dirty War, Cambodian–Vietnamese War, and others.[70][71]

Protest in Amsterdam against the nuclear arms race between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, 1981

In 1956, following the declaration of the Imre Nagy government of the withdrawal of Hungary from the Warsaw Pact, Soviet troops entered the country and removed the government.[72] Soviet forces crushed the nationwide revolt, leading to the death of an estimated 2,500 Hungarian citizens.[73]

The multi-national Communist armed forces’ sole joint action was the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, another Warsaw Pact member state, in August 1968.[74] All member countries, with the exception of the Socialist Republic of Romania and the People’s Republic of Albania, participated in the invasion.[75] The German Democratic Republic provided only minimal support.[75]

End of the Cold War[edit]

In 1989, popular civil and political public discontent toppled the Communist governments of the Warsaw Treaty countries. The beginning of the end of the Warsaw Pact, regardless of military power, was the Pan-European Picnic in August 1989. The event, which goes back to an idea by Otto von Habsburg, caused the mass exodus of GDR citizens and the media-informed population of Eastern Europe felt the loss of power of their rulers and the Iron Curtain broke down completely. Though Poland’s new Solidarity government under Lech Wałęsa initially assured the Soviets that it would remain in the Pact,[76] this broke the brackets of Eastern Europe, which could no longer be held together militarily by the Warsaw Pact.[77][78][79] Independent national politics made feasible with the perestroika and liberal glasnost policies revealed shortcomings and failures (i.e. of the soviet-type economic planning model) and have induced institutional collapse of the Communist government in the USSR in 1991.[80][better source needed] From 1989 to 1991, Communist governments were overthrown in Albania, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union.

As the last acts of the Cold War were playing out, several Warsaw Pact states (Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary) participated in the US-led coalition effort to liberate Kuwait in the Gulf War.

On 25 February 1991, the Warsaw Pact was declared disbanded at a meeting of defence and foreign ministers from remaining Pact countries meeting in Hungary.[81] On 1 July 1991, in Prague, the Czechoslovak President Václav Havel[82] formally ended the 1955 Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance and so disestablished the Warsaw Treaty after 36 years of military alliance with the USSR.[82][83] The USSR disestablished itself in December 1991.

Structure[edit]

The Warsaw Treaty’s organization was two-fold: the Political Consultative Committee handled political matters, and the Combined Command of Pact Armed Forces controlled the assigned multi-national forces, with headquarters in Warsaw, Poland.

Although an apparently similar collective security alliance, the Warsaw Pact differed substantially from NATO. De jure, the eight-member countries of the Warsaw Pact pledged the mutual defense of any member who would be attacked; relations among the treaty signatories were based upon mutual non-intervention in the internal affairs of the member countries, respect for national sovereignty, and political independence.[84]

However, de facto, the Pact was a direct reflection of the USSR’s authoritarianism and undisputed domination over the Eastern Bloc, in the context of the so-called Soviet Empire, which was not comparable to that of the United States over the Western Bloc.[85] All Warsaw Pact commanders had to be, and have been, senior officers of the Soviet Union at the same time and appointed for an unspecified term length: the Supreme Commander of the Unified Armed Forces of the Warsaw Treaty Organization, which commanded and controlled all the military forces of the member countries, was also a First Deputy Minister of Defence of the USSR, and the Chief of Combined Staff of the Unified Armed Forces of the Warsaw Treaty Organization was also a First Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Soviet Armed Forces.[86] On the contrary, the Secretary General of NATO and Chair of the NATO Military Committee are positions with fixed term of office held on a random rotating basis by officials from all member countries through consensus.

Despite the American hegemony (mainly military and economic) over NATO, all decisions of the North Atlantic Alliance required unanimous consensus in the North Atlantic Council and the entry of countries into the alliance was not subject to domination but rather a natural democratic process.[85] In the Warsaw Pact, decisions were ultimately taken by the Soviet Union alone; the countries of the Warsaw Pact were not equally able to negotiate their entry in the Pact nor the decisions taken.[85]

Although nominally a «defensive» alliance, the Pact’s primary function was to safeguard the Soviet Union’s hegemony over its Eastern European satellites, with the Pact’s only direct military actions having been the invasions of its own member states to keep them from breaking away.[87]

Romania and Albania[edit]

The Warsaw Pact before its 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, showing the Soviet Union and its satellites (red) and the two independent non-Soviet members: Romania and Albania (pink)

Romania and, until 1968, Albania – were exceptions. Together with Yugoslavia, which broke with the Soviet Union before the Warsaw Pact was created, these three countries completely rejected the Soviet doctrine formulated for the Pact. Albania officially left the organization in 1968, in protest of its invasion of Czechoslovakia. Romania had its own reasons for remaining a formal member of the Warsaw Pact, such as Nicolae Ceaușescu’s interest of preserving the threat of a Pact invasion so he could sell himself as a nationalist, as well as privileged access to NATO counterparts and a seat at various European forums which otherwise he would not have had (for instance, Romania and the Soviet-led remainder of the Warsaw Pact formed two distinct groups in the elaboration of the Helsinki Final Act).[88] When Andrei Grechko assumed command of the Warsaw Pact, both Romania and Albania had for all practical purposes defected from the Pact. In the early 1960s, Grechko initiated programs meant to preempt Romanian doctrinal heresies from spreading to other Pact members. Romania’s doctrine of territorial defense threatened the Pact’s unity and cohesion. No other country succeeded in escaping from the Warsaw Pact like Romania and Albania did. For example, the mainstays of Romania’s tank forces were locally-developed models. Soviet troops were deployed to Romania for the last time in 1963, as part of a Warsaw Pact exercise. After 1964, the Soviet Army was barred from returning to Romania, as the country refused to take part in joint Pact exercises.[89]

A Romanian TR-85 tank in December 1989 (Romania’s TR-85 and TR-580 tanks were the only non-Soviet tanks in the Warsaw Pact on which restrictions were placed under the 1990 CFE Treaty[90])

Even before the advent of Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romania was in fact an independent country, as opposed to the rest of the Warsaw Pact. To some extent, it was even more independent than Cuba (a communist Soviet-aligned state that was not a member of the Warsaw Pact).[1] The Romanian regime was largely impervious to Soviet political influence, and Ceaușescu was the only declared opponent of glasnost and perestroika. On account of the contentious relationship between Bucharest and Moscow, the West did not hold the Soviet Union responsible for the policies pursued by Bucharest. This was not the case for the other countries in the region, such as Czechoslovakia and Poland.[91] At the start of 1990, the Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, implicitly confirmed the lack of Soviet influence over Ceaușescu’s Romania. When asked whether it made sense for him to visit Romania less than two weeks after its revolution, Shevardnadze insisted that only by going in person to Romania could he figure out how to «restore Soviet influence».[92]

Romania requested and obtained the complete withdrawal of the Soviet Army from its territory in 1958. The Romanian campaign for independence culminated on 22 April 1964 when the Romanian Communist Party issued a declaration proclaiming that: «Every Marxist-Leninist Party has a sovereign right…to elaborate, choose or change the forms and methods of socialist construction.» and «There exists no «parent» party and «offspring» party, no «superior» and «subordinated» parties, but only the large family of communist and workers’ parties having equal rights.» and also «there are not and there can be no unique patterns and recipes». This amounted to a declaration of political and ideological independence from Moscow.[93][94][95][96]

The Romanian IAR-93 Vultur was the only combat jet designed and built by a non-Soviet member of the Warsaw Pact.[97]

Following Albania’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, Romania remained the only Pact member with an independent military doctrine which denied the Soviet Union use of its armed forces and avoided absolute dependence on Soviet sources of military equipment.[98] Romania was the only non-Soviet Warsaw Pact member which was not obliged to militarily defend the Soviet Union in case of an armed attack.[99] Bulgaria and Romania were the only Warsaw Pact members that did not have Soviet troops stationed on their soil.[100] In December 1964, Romania became the only Warsaw Pact member (save Albania, which would leave the Pact altogether within 4 years) from which all Soviet advisors were withdrawn, including those in the intelligence and security services.[101] Not only did Romania not participate in joint operations with the KGB, but it also set up «departments specialized in anti-KGB counterespionage».[102]

Romania was neutral in the Sino-Soviet split.[103][104][105] Its neutrality in the Sino-Soviet dispute along with being the small Communist country with the most influence in global affairs enabled Romania to be recognized by the world as the «third force» of the Communist world. Romania’s independence – achieved in the early 1960s through its freeing from its Soviet satellite status – was tolerated by Moscow because Romania was not bordering the Iron Curtain – being surrounded by socialist states – and because its ruling party was not going to abandon communism.[2][106][107]

Although certain historians such as Robert King and Dennis Deletant argue against the usage of the term «independent» to describe Romania’s relations with the Soviet Union, favoring «autonomy» instead on account of the country’s continued membership within both the Comecon and the Warsaw Pact along with its commitment to socialism, this approach fails to explain why in July 1963 Romania blocked Mongolia’s accession to the Warsaw Pact, why in November 1963 Romania voted in favor of a UN resolution to establish a nuclear-free zone in Latin America when the other Soviet-aligned countries abstained, or why in 1964 Romania opposed the Soviet-proposed «strong collective riposte» against China (and these are examples solely from the 1963–1964 period).[108] Soviet disinformation tried to convince the West that Ceaușescu’s empowerment was a dissimulation in connivance with Moscow.[109] To an extent this worked, as some historians came to see the hand of Moscow behind every Romanian initiative. For instance, when Romania became the only Eastern European country to maintain diplomatic relations with Israel, some historians have speculated that this was at Moscow’s whim. However, this theory fails upon closer inspection.[110] Even during the Cold War, some thought that Romanian actions were done at the behest of the Soviets, but Soviet anger at said actions was «persuasively genuine». In truth, the Soviets were not beyond publicly aligning themselves with the West against the Romanians at times.[111]

Strategy[edit]

The strategy behind the formation of the Warsaw Pact was driven by the desire of the Soviet Union to prevent Central and Eastern Europe being used as a base for its enemies. Its policy was also driven by ideological and geostrategic reasons. Ideologically, the Soviet Union arrogated the right to define socialism and communism and act as the leader of the global socialist movement. A corollary to this was the necessity of military intervention if a country appeared to be «violating» core socialist ideas, i.e. breaking away from the Soviet sphere of influence, explicitly stated in the Brezhnev Doctrine.[112]

Notable military exercises[edit]

| External video |

|---|

- «Szczecin» (Poland, 1962)

- «Vltava» (Czechoslovakia, 1966)

- Operation «Rhodope» (Bulgaria, 1967)

- «Oder-Neisse» (East Germany, 1969)

- Przyjaźń 84 (Poland, 1984)

- Shield 84 (Czechoslovakia, 1984)[113]

NATO and Warsaw Pact: comparison of the two forces[edit]

NATO and Warsaw Pact forces in Europe[edit]

| NATO estimates | Warsaw Pact

estimates |

|||

| Type | NATO | Warsaw Pact | NATO | Warsaw Pact |

| Personnel | 2,213,593 | 3,090,000 | 3,660,200 | 3,573,100 |

| Combat aircraft | 3,977 | 8,250 | 7,130 | 7,876 |

| Total strike aircraft | NA | NA | 4,075 | 2,783 |

| Helicopters | 2,419 | 3,700 | 5,720 | 2,785 |

| Tactical missile launchers | NA | NA | 136 | 1,608 |

| Tanks | 16,424 | 51,500 | 30,690 | 59,470 |

| Anti-tank weapons | 18,240 | 44,200 | 18,070 | 11,465 |

| Armored infantry fighting vehicles | 4,153 | 22,400 | 46,900 | 70,330 |

| Artillery | 14,458 | 43,400 | 57,060 | 71,560 |

| Other armored vehicles | 35,351 | 71,000 | ||

| Armored vehicle launch bridges | 454 | 2,550 | ||

| Air defense systems | 10,309 | 24,400 | ||

| Submarines | 200 | 228 | ||

| Submarines (nuclear powered) | 76 | 80 | ||

| Large surface ships | 499 | 102 | ||

| Aircraft-carrying ships | 15 | 2 | ||

| Aircraft-carrying ships armed with cruise missiles | 274 | 23 | ||

| Amphibious warfare ships | 84 | 24 |

Post–Warsaw Pact[edit]

Expansion of NATO before and after the collapse of communism throughout Central and Eastern Europe

On 12 March 1999, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland joined NATO; Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia joined in March 2004; Albania joined on 1 April 2009.[115][116]

The USSR’s successor Russia and some other post-Soviet states joined the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 1992, and the Shanghai Five in 1996, which was renamed the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) after Uzbekistan’s addition in 2001.[citation needed]

In November 2005, the Polish government opened its Warsaw Treaty archives to the Institute of National Remembrance, which published some 1,300 declassified documents in January 2006, yet the Polish government reserved publication of 100 documents, pending their military declassification. Eventually, 30 of the reserved 100 documents were published; 70 remained secret and unpublished. Among the documents published was the Warsaw Treaty’s nuclear war plan, Seven Days to the River Rhine – a short, swift invasion and capture of Austria, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands east of the Rhine, using nuclear weapons after a supposed NATO first strike.[117][118]

See also[edit]

- Eastern Bloc

- Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 – treaty that defined Finland’s level of neutrality towards Soviet Union

- Finlandization – the USSR’s influence on Finland following the treaty

- Russosphere

- Soviet Empire

- Sovietization

- Treaty of friendship – any treaty establishing close ties between countries

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Withheld support in 1961 due to the Soviet–Albanian split, but formally withdrew in 1968.

- ^ Formally withdrew in September 1990.

- ^ The only independent permanent non-Soviet member of the Warsaw Pact, having freed itself from its Soviet satellite status by the early 1960s.[1][2]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Tismaneanu, Vladimir; Stan, Marius (17 May 2018). Vladimir Tismaneanu, Marius Stan, Cambridge University Press, 17 May, 2018, Romania Confronts Its Communist Past: Democracy, Memory, and Moral Justice, p. 132. ISBN 9781107025929.

- ^ a b c Cook, Bernard A.; Cook, Bernard Anthony (2001). Bernard A. Cook, Bernard Anthony Cook, Taylor & Francis, 2001, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, p. 1075. ISBN 9780815340584.

- ^ «Introduction». www.php.isn.ethz.ch.

- ^ «Text of Warsaw Pact» (PDF). United Nations Treaty Collection. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ «Milestones: 1953–1960 — Office of the Historian». history.state.gov.

- ^ Yost, David S. (1998). NATO Transformed: The Alliance’s New Roles in International Security. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-878379-81-X.

- ^ a b c «Formation of Nato and Warsaw Pact». History Channel. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b c «The Warsaw Pact is formed». History Channel. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b «In reaction to West Germany’s NATO accession, the Soviet Union and its Eastern European client states formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955.» Citation from: NATO website. «A short history of NATO». nato.int. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ Broadhurst, Arlene Idol (1982). The Future of European Alliance Systems. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-86531-413-6.

- ^ Christopher Cook, Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983)

- ^ The Columbia Enclopedia, fifth edition (1993) p. 2926

- ^ a b Laurien Crump (2015). The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered: International Relations in Eastern Europe, 1955–1969. Routledge, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Debra J. Allen. The Oder-Neisse Line: The United States, Poland, and Germany in the Cold War. p. 158. «Treaties approving Bonn’s participation in NATO were ratified in May 1955…shortly thereafter Soviet Union…created the Warsaw Pact to counter the perceived threat of NATO»

- ^ a b Amos Yoder (1993). Communism in Transition: The End of the Soviet Empires. Taylor & Francis. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8448-1738-5. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ a b Bob Reinalda (11 September 2009). Routledge History of International Organizations: From 1815 to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 369. ISBN 978-1-134-02405-6. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ [1] Archived 23 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Cover Story: The Holy Alliance By Carl Bernstein Sunday, 24 June 2001

- ^ Thomas Roser: DDR-Massenflucht: Ein Picknick hebt die Welt aus den Angeln (German – Mass exodus of the GDR: A picnic clears the world) in: Die Presse 16 August 2018

- ^ Europa Antoni Czubiński Wydawn. Poznańskie, 1998, p. 298

- ^ World Politics: The Menu for Choice page 87

Bruce Russett, Harvey Starr, David Kinsella – 2009 The Warsaw Pact was established in 1955 as a response to West Germany’s entry into NATO; German militarism was still a recent memory among the Soviets and East Europeans. - ^ «When the Federal Republic of Germany entered NATO in early May 1955, the Soviets feared the consequences of a strengthened NATO and a rearmed West Germany». Citation from:United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. «The Warsaw Treaty Organization, 1955». Office of the Historian. history.state.gov. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ «1955: After objecting to Germany’s admission into NATO, the Soviet Union joins Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania in forming the Warsaw Pact.». See chronology in:«Fast facts about NATO». CBC News. 6 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Laurien Crump (2015). The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered: International Relations in Eastern Europe, 1955–1969. Routledge. p. 17

- ^ Laurien Crump (2015). The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered: International Relations in Eastern Europe, 1955–1969. Routledge. p. 1.

- ^ «Soviet Union request to join NATO» (PDF). Nato.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ «1954: Soviet Union suggests it should join NATO to preserve peace in Europe. U.S. and U.K. reject this». See chronology in:«Fast facts about NATO». CBC News. 6 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b «Proposal of Soviet adherence to NATO as reported in the Foreign Relations of the United States Collection». UWDC FRUS Library. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, pp. 197, 201.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, p. 202.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, pp. 197–198, 203, 212.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, pp. 211–212, 216.

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (1991). The German Question: The Stalin Note of 1952 and the Problem of Reunification. Columbia Univ Press. p. 56.

- ^ Gaddis, John (1997). We Know Now: Rethinking Cold War History. Clarendon Press. p. 126.

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (1991). The German Question: The Stalin Note of 1952 and the Problem of Reunification. Columbia Univ Press. p. 80.

- ^ Steininger, Rolf (1991). The German Question: The Stalin Note of 1952 and the Problem of Reunification. Columbia Univ Press. p. 103.

- ^ a b «Draft general European Treaty on collective security in Europe — Molotov proposal (Berlin, 10 February 1954)» (PDF). CVCE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d «MOLOTOV’S PROPOSAL THAT THE USSR JOIN NATO, MARCH 1954». Wilson Center. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Molotov 1954a, p. 216,.

- ^ «Final text of tripartite reply to Soviet note» (PDF). Nato website. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Ian Traynor (17 June 2001). «Soviets tried to join Nato in 1954». the Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ «Memo by Lord Ismay, Secretary General of NATO» (PDF). Nato.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Adenauer 1966a, p. 662.

- ^ «The refusal to ratify the EDC Treaty». CVCE. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ «Debates in the French National Assembly on 30 August 1954». CVCE. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ «US positions on alternatives to EDC». United States Department of State / FRUS collection. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ «US positions on german rearmament outside NATO». United States Department of State / FRUS collection. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ «West Germany accepted into Nato». BBC News. 9 May 1955. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ «Indivisible Germany: Illusion or Reality?» James H. Wolfe

Springer Science & Business Media, 6 December 2012 page 73 - ^ a b «Text of the Warsaw Security Pact (see preamble)». Avalon Project. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ «No shooting please, we’re German». The Economist. 13 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Mark Kramer, «The Soviet Bloc and the Cold War in Europe,» in Larresm, Klaus, ed. (2014). A Companion to Europe Since 1945. Wiley. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-118-89024-0.

- ^ spiegel.de: Warum steht in Polen eine Sowjet-Garnison? (Der Spiegel 20/1983)

- ^ see also Group of Soviet Forces in Germany

- ^ see also History of Romania#Communist period (1947–1989)

- ^ Agreement on the Legal Status of the Soviet Forces Temporarily Present on the Territory of the Hungarian People’s Republic (The American Journal of International Law Vol. 52, No. 1 (Jan., 1958), pp. 215-221)

- ^ a b c d e «The Warsaw Pact is formed — May 14, 1955 — HISTORY.com». Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Webb, Adrian (9 September 2014). Adrian Webb, Routledge, 9 sept. 2014, Longman Companion to Germany Since 1945, p. 59. ISBN 9781317884248.

- ^ Bozo, Édéric (2009). Frédéric Bozo, Berghahn Books, 2009, Mitterrand, the End of the Cold War, and German Unification, p. 297. ISBN 9781845457877.

- ^ Winkler, Heinrich August (2006). Heinrich August Winkler, Oxford University Press, 2006, Germany: 1933-1990, p. 537. ISBN 978-0-19-926598-5.

- ^ Childs, David (17 December 2014). David Childs, Routledge, 17 dec. 2014, Germany in the Twentieth Century, p. 261. ISBN 9781317542285.

- ^ Gray, Richard T.; Wilke, Sabine (1996). Richard T. Gray, Sabine Wilke, University of Washington Press, 1996, German Unification and Its Discontents, p. 54 (LIV). ISBN 9780295974910.

- ^ a b Mastny, Vojtech; Byrne, Malcolm (1 January 2005). A Cardboard Castle?: An Inside History of the Warsaw Pact, 1955-1991. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789637326080. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Crump, Laurien (2015). The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered: International Relations in Eastern Europe, 1955–1969. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 9781317555308.

- ^ Lüthi, Lorenz M. (19 March 2020). Lorenz M. Lüthi, Cambridge University Press, Mar 19, 2020, Cold Wars: Asia, the Middle East, Europe, p. 398. ISBN 9781108418331.

- ^ «Soviet Troops to Leave Mongolia in 2 Years». Reuters. 3 March 1990. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018 – via LA Times.

- ^ ABC-CLIO (3 March 1990). «Warsaw Treaty Organization». Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Lüthi, Lorenz M. (8 October 2007). «The People’s Republic of China and the Warsaw Pact Organization, 1955-63». Cold War History. 7 (4): 479–494. doi:10.1080/14682740701621762. S2CID 153463433. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ «1968 — The Prague Spring». Austria 1989 — Year of Miracles. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

In the morning hours of August 21, 1968, Soviet and Warsaw Pact tanks roll in the streets of Prague; to distinguish them from Czechoslovak tanks, they are marked with white crosses.

- ^ «America Wasn’t the Only Foreign Power in the Vietnam War». 2 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ «Crisis Points of the Cold War — Boundless World History». courses.lumenlearning.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ «The Hungarian Uprising of 1956 — History Learning Site». Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Percival, Matthew (23 October 2016). «Recalling the Hungarian revolution, 60 years on». CNN. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ «Soviets Invade Czechoslovakia — Aug 20, 1968 — HISTORY.com». Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b Nosowska, Agnieszka. «Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia». www.enrs.eu. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Trainor, Bernard E. (22 August 1989). «Polish Army: Enigma in the Soviet Alliance». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Miklós Németh in Interview with Peter Bognar, Grenzöffnung 1989: „Es gab keinen Protest aus Moskau“ (German — Border opening in 1989: There was no protest from Moscow), in: Die Presse 18 August 2014.

- ^ „Der 19. August 1989 war ein Test für Gorbatschows“ (German — 19 August 1989 was a test for Gorbachev), in: FAZ 19 August 2009.

- ^ Michael Frank: Paneuropäisches Picknick – Mit dem Picknickkorb in die Freiheit (German: Pan-European picnic — With the picnic basket to freedom), in: Süddeutsche Zeitung 17 May 2010.

- ^ The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, third edition, 1999, pp. 637–8

- ^ «Warsaw Pact and Comecon To Dissolve This Week». Csmonitor.com. 26 February 1991. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Steven (2 July 1991). «DEATH KNELL RINGS FOR WARSAW PACT». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Havel, Václav (2007). To the Castle and Back. Trans. Paul Wilson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26641-5. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ «How the Russians Used the Warsaw Pact». Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b c «Differences Between Nato and the Warsaw Pact». Atlantische Tijdingen (57): 1–16. 1967. JSTOR 45343492. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Fes’kov, V. I.; Kalashnikov, K. A.; Golikov, V. I. (2004). Sovetskai͡a Armii͡a v gody «kholodnoĭ voĭny,» 1945–1991 [The Soviet Army in the Cold War Years (1945–1991)]. Tomsk: Tomsk University Publisher. p. 6. ISBN 5-7511-1819-7.

- ^ This day in history: the Warsaw Pact ends

- ^ Ben-Dor, Gabriel; Dewitt, David Brian (1987). Gabriel Ben-Dor, David Brian Dewitt, Lexington Books, 1987, Conflict Management in the Middle East, p. 242. ISBN 9780669141733.

- ^ Goldman, Emily O.; Eliason, Leslie C. (2003). Emily O. Goldman, Leslie C. Eliason, Stanford University Press, 2003, The Diffusion of Military Technology and Ideas, pp. 140-143. ISBN 9780804745352.

- ^ «Office of Public Communication, Bureau of Public Affairs, 1991, US Department of State Dispatch, Volume 2, p. 13″. 1991.

- ^ Lévesque, Jacques (28 May 2021). Jacques Lévesque, University of California Press, May 28, 2021, The Enigma of 1989: The USSR and the Liberation of Eastern Europe, pp. 192-193. ISBN 9780520364981.

- ^ Service, Robert (8 October 2015). Robert Service, Pan Macmillan, 8 October 2015, The End of the Cold War: 1985 — 1991, p. 429. ISBN 9781447287285.

- ^ McDermott, Kevin; Stibbe, Matthew (29 May 2018). Kevin McDermott, Matthew Stibbe, Springer, May 29, 2018, Eastern Europe in 1968: Responses to the Prague Spring and Warsaw Pact Invasion, p. 195. ISBN 9783319770697.

- ^ Eyal, Jonathan (18 June 1989). Jonathan Eyal, Springer, Jun 18, 1989, Warsaw Pact and the Balkans: Moscow’s Southern Flank, p. 68. ISBN 9781349099412.

- ^ Valdez, Jonathan C. (29 April 1993). Jonathan C. Valdez, Cambridge University Press, Apr 29, 1993, Internationalism and the Ideology of Soviet Influence in Eastern Europe, p. 51. ISBN 9780521414388.

- ^ Burks, Richard Voyles (8 December 2015). Richard Voyles Burks, Princeton University Press, Dec 8, 2015, Dynamics of Communism in Eastern Europe, p. XVI. ISBN 9781400877225.

- ^ «Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Incorporated, 1994, RFE/RL Research Report: Weekly Analyses from the RFE/RL Research Institute, Volume 3, p. 3». 1994.

- ^ Leebaert, Derek; Dickinson, Timothy (1992). Derek Leebaert, Timothy Dickinson, Cambridge University Press, 1992, Soviet Strategy and the New Military Thinking, pp. 102, 110 and 113-114. ISBN 9780521407694.

- ^ Eyal, Jonathan (18 June 1989). Jonathan Eyal, Springer, Jun 18, 1989, Warsaw Pact and the Balkans: Moscow’s Southern Flank, p. 74. ISBN 9781349099412.

- ^ Dickerson, M. O.; Flanagan, Thomas (1990). M. O. Dickerson, Thomas Flanagan, Nelson Canada, 1990, An Introduction to Government and Politics: A Conceptual Approach, p. 75. ISBN 9780176034856.

- ^ Crampton, R. J. (15 July 2014). R. J. Crampton, Routledge, Jul 15, 2014, The Balkans Since the Second World War, p. 189. ISBN 9781317891178.

- ^ Carey, Henry F. (2004). Henry F. Carey, Lexington Books, 2004, Romania Since 1989: Politics, Economics, and Society, p. 536. ISBN 9780739105924.

- ^ Brinton, Crane; Christopher, John B.; Wolff, Robert Lee (1973). Crane Brinton, John B. Christopher, Robert Lee Wolff, Prentice-Hall, 1973, Civilization in the West, p. 683. ISBN 9780131350120.

- ^ Ebenstein, William; Fogelman, Edwin (1980). William Ebenstein, Edwin Fogelman, Prentice-Hall, 1980, Today’s Isms: Communism, Fascism, Capitalism, Socialism, p. 68. ISBN 9780139243998.

- ^ Shafir, Michael (1985). Michael Shafir, Pinter, 1985, Romania: Politics, Economics and Society : Political Stagnation and Simulated Change, p. 177. ISBN 9780861874385.

- ^ Ascoli, Max (1965). «Max Ascoli, Reporter Magazine, Company, 1965, The Reporter, Volume 33, p. 32″.

- ^ «Yong Liu, Institutul Național pentru Studiul Totalitarismului, 2006, Sino-Romanian Relations: 1950’s-1960’s, p. 199″.

- ^ Dragomir, Elena (12 January 2015). Elena Dragomir, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 12 January 2015, Cold War Perceptions: Romania’s Policy Change towards the Soviet Union, 1960-1964, p. 14. ISBN 9781443873031.

- ^ Abraham, Florin (17 November 2016). Florin Abraham, Bloomsbury Publishing, Nov 17, 2016, Romania since the Second World War: A Political, Social and Economic History, p. 61. ISBN 9781472529923.

- ^ Navon, Emmanuel (November 2020). Emmanuel Navon, University of Nebraska Press, 2020, The Star and the Scepter: A Diplomatic History of Israel, p. 307. ISBN 9780827618602.

- ^ Alexander, Michael (2005). Michael Alexander, Royal United Services Institute, 2005, Managing the Cold War: A View from the Front Line, pp. 85-86. ISBN 9780855161910.