|

|||

| Full name | Football Club Internazionale Milano S.p.A.[1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) |

|

||

| Short name | Inter | ||

| Founded | 9 March 1908; 115 years ago (as Football Club Internazionale) | ||

| Ground | Giuseppe Meazza | ||

| Capacity | 75,923 | ||

| Owner |

|

||

| Chairman | Steven Zhang[7] | ||

| Head coach | Simone Inzaghi | ||

| League | Serie A | ||

| 2021–22 | Serie A, 2nd of 20 | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

|||

Football Club Internazionale Milano, commonly referred to as Internazionale (pronounced [ˌinternattsjoˈnaːle]) or simply Inter, and colloquially known as Inter Milan in English-speaking countries,[8][9][10] is an Italian professional football club based in Milan, Lombardy. Inter is the only Italian side to have always competed in the top flight of Italian football since its debut in 1909.

Founded in 1908 following a schism within the Milan Cricket and Football Club (now AC Milan), Inter won its first championship in 1910. Since its formation, the club has won 34 domestic trophies, including 19 league titles, 8 Coppa Italia and 7 Supercoppa Italiana. From 2006 to 2010, the club won five successive league titles, equalling the all-time record at that time.[11] They have won the Champions League three times: two back-to-back in 1964 and 1965 and then another in 2010. Their latest win completed an unprecedented Italian seasonal treble, with Inter winning the Coppa Italia and the Scudetto the same year.[12] The club has also won three UEFA Cups, two Intercontinental Cups and one FIFA Club World Cup.

Inter’s home games are played at the San Siro stadium, which they share with city rivals Milan. The stadium is the largest in Italian football with a capacity of 75,817.[13] They have long-standing rivalries with Milan, with whom they contest the Derby della Madonnina, and Juventus, with whom they contest the Derby d’Italia; their rivalry with the former is one of the most followed derbies in football.[14] As of 2019, Inter has the highest home game attendance in Italy and the sixth highest attendance in Europe.[15] Since 2016, the club has been majority-owned by Chinese holding company Suning Holdings Group.[2] Inter is one of the most valuable in Italian and world football.[16]

History

Foundation and early years (1908–1960)

|

|

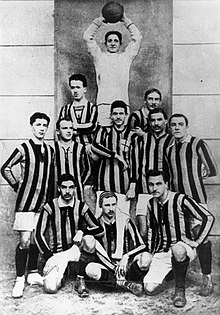

The club was founded on 9 March 1908 as Football Club Internazionale, following the schism with the Milan Cricket and Football Club (now AC Milan). The name of the club derives from the wish of its founding members to accept foreign players without limits as well as Italians.

The club won its first championship in 1910 and its second in 1920. The captain and coach of the first championship winning team was Virgilio Fossati, who was later killed in battle while serving in the Italian army during World War I. In 1922, Inter was at risk of relegation to the second division, but they remained in the top league after winning two play-offs.

Six years later, during the Fascist era, the club was forced to merge with the Unione Sportiva Milanese and was renamed Società Sportiva Ambrosiana.[18] During the 1928–29 season, the team wore white jerseys with a red cross emblazoned on it; the jersey’s design was inspired by the flag and coat of arms of the city of Milan. In 1929, the new club chairman Oreste Simonotti changed the club’s name to Associazione Sportiva Ambrosiana and restored the previous black-and-blue jerseys, however supporters continued to call the team Inter, and in 1931 new chairman Pozzani caved in to shareholder pressure and changed the name to Associazione Sportiva Ambrosiana-Inter.

Giuseppe Meazza still holds the record for the most goals scored in a debut season in Serie A, with 31 goals in his first season (1929–30).

Their first Coppa Italia (Italian Cup) was won in 1938–39, led by the iconic Giuseppe Meazza, after whom the San Siro stadium is officially named. A fifth championship followed in 1940, despite Meazza incurring an injury. After the end of World War II the club regained its original name, winning its sixth championship in 1953 and its seventh in 1954.

Grande Inter (1960–1967)

In 1960, manager Helenio Herrera joined Inter from Barcelona, bringing with him his midfield general Luis Suárez, who won the European Footballer of the Year in the same year for his role in Barcelona’s La Liga/Fairs Cup double. He would transform Inter into one of the greatest teams in Europe. He modified a 5–3–2 tactic known as the «Verrou» («door bolt») which created greater flexibility for counterattacks. The catenaccio system was invented by an Austrian coach, Karl Rappan. Rappan’s original system was implemented with four fixed defenders, playing a strict man-to-man marking system, plus a playmaker in the middle of the field who plays the ball together with two midfield wings. Herrera would modify it by adding a fifth defender, the sweeper or libero behind the two centre backs. The sweeper or libero who acted as the free man would deal with any attackers who went through the two centre backs. Inter finished third in the Serie A in his first season, second the next year and first in his third season. Then followed a back-to-back European Cup victory in 1964 and 1965, earning him the title «il Mago» («the Wizard»). The core of Herrera’s team were the attacking fullbacks Tarcisio Burgnich and Giacinto Facchetti, Armando Picchi the sweeper, Suárez the playmaker, Jair the winger, Mario Corso the left midfielder, and Sandro Mazzola, who played on the inside-right.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

Sandro Mazzola played for the highly successful Inter team remembered by the name of «La Grande Inter», during the 1960s.

In 1964, Inter reached the European Cup Final by beating Borussia Dortmund in the semi-final and Partizan in the quarter-final. In the final, they met Real Madrid, a team that had reached seven out of the nine finals to date. Mazzola scored two goals in a 3–1 victory, and then the team won the Intercontinental Cup against Independiente. A year later, Inter repeated the feat by beating two-time winner Benfica in the final held at home, from a Jair goal, and then again beat Independiente in the Intercontinental Cup. In 1967, with Suárez injured, Inter lost the European Cup Final 2–1 to Celtic. During that year the club changed its name to Football Club Internazionale Milano.

Subsequent achievements (1967–1991)

Following the golden era of the 1960s, Inter managed to win their eleventh league title in 1971 and their twelfth in 1980. Inter were defeated for the second time in five years in the final of the European Cup, going down 0–2 to Johan Cruyff’s Ajax in 1972. During the 1970s and the 1980s, Inter also added two to its Coppa Italia tally, in 1977–78 and 1981–82.

Hansi Müller (1975–1982 VfB Stuttgart, 1982–1984 Inter Milan) and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge (1974–1984 Bayern Munich, 1984–1987 Inter Milan) played for Inter Milan. Led by the German duo of Andreas Brehme and Lothar Matthäus, and Argentine Ramón Díaz, Inter captured the 1989 Serie A championship. Inter were unable to defend their title despite adding fellow German Jürgen Klinsmann to the squad and winning their first Supercoppa Italiana at the start of the season.

Mixed fortunes (1991–2004)

The 1990s was a period of disappointment. While their great rivals Milan and Juventus were achieving success both domestically and in Europe, Inter were left behind, with repeated mediocre results in the domestic league standings, their worst coming in 1993–94 when they finished just one point out of the relegation zone. Nevertheless, they achieved some European success with three UEFA Cup victories in 1991, 1994 and 1998.

With Massimo Moratti’s takeover from Ernesto Pellegrini in 1995, Inter twice broke the world record transfer fee in this period (£19.5 million for Ronaldo from Barcelona in 1997 and £31 million for Christian Vieri from Lazio two years later).[25] However, the 1990s remained the only decade in Inter’s history in which they did not win a single Serie A championship. For Inter fans, it was difficult to find who in particular was to blame for the troubled times and this led to some icy relations between them and the chairman, the managers and even some individual players.

Jerseys of Ronaldo (number 10), Zamorano (one plus eight) and Figo (seven) in the San Siro museum

Moratti later became a target of the fans, especially when he sacked the much-loved coach Luigi Simoni after only a few games into the 1998–99 season, having just received the Italian manager of the year award for 1998 the day before being dismissed. That season, Inter failed to qualify for any European competition for the first time in almost ten years, finishing in eighth place.

The following season, Moratti appointed former Juventus manager Marcello Lippi, and signed players such as Angelo Peruzzi and Laurent Blanc together with other former Juventus players Vieri and Vladimir Jugović. The team came close to their first domestic success since 1989 when they reached the Coppa Italia final only to be defeated by Lazio.

Inter’s misfortunes continued the following season, losing the 2000 Supercoppa Italiana match against Lazio 4–3 after initially taking the lead through new signing Robbie Keane. They were also eliminated in the preliminary round of the Champions League by Swedish club Helsingborgs IF, with Álvaro Recoba missing a crucial late penalty. Lippi was sacked after only a single game of the new season following Inter’s first ever Serie A defeat to Reggina. Marco Tardelli, chosen to replace Lippi, failed to improve results, and is remembered by Inter fans as the manager that lost 6–0 in the city derby against Milan. Other members of the Inter «family» during this period that suffered were the likes of Vieri and Fabio Cannavaro, both of whom had their restaurants in Milan vandalised after defeats to the Rossoneri.

In 2002, not only did Inter manage to make it to the UEFA Cup semi-finals, but were also only 45 minutes away from capturing the Scudetto when they needed to maintain their one-goal advantage away to Lazio. Inter were 2–1 up after only 24 minutes. Lazio equalised during first half injury time and then scored two more goals in the second half to clinch victory that eventually saw Juventus win the championship. The next season, Inter finished as league runners-up and also managed to make it to the 2002–03 Champions League semi-finals against Milan, losing on the away goals rule.

Comeback and unprecedented treble (2004–2011)

On 8 July 2004, Inter appointed former Lazio coach Roberto Mancini as its new head coach. In his first season, the team collected 72 points from 18 wins, 18 draws and only two losses, as well as winning the Coppa Italia and later the Supercoppa Italiana. On 11 May 2006, Inter retained their Coppa Italia title once again after defeating Roma with a 4–1 aggregate victory (a 1–1 scoreline in Rome and a 3–1 win at the San Siro).

Inter were awarded the 2005–06 Serie A championship retrospectively after title-winning Juventus was relegated and points were stripped from Milan due to the Calciopoli scandal. During the following season, Inter went on a record-breaking run of 17 consecutive victories in Serie A, starting on 25 September 2006 with a 4–1 home victory over Livorno, and ending on 28 February 2007, after a 1–1 draw at home to Udinese. On 22 April 2007, Inter won their second consecutive Scudetto—and first on the field since 1989—when they defeated Siena 2–1 at Stadio Artemio Franchi. Italian World Cup-winning defender Marco Materazzi scored both goals.[26]

Inter started the 2007–08 season with the goal of winning both Serie A and Champions League. The team started well in the league, topping the table from the first round of matches, and also managed to qualify for the Champions League knockout stage. However, a late collapse, leading to a 2–0 defeat with ten men away to Liverpool on 19 February in the Champions League, threw into question manager Roberto Mancini’s future at Inter while domestic form took a sharp turn of fortune with the team failing to win in the three following Serie A games. After being eliminated by Liverpool in the Champions League, Mancini announced his intention to leave his job immediately only to change his mind the following day. On the final day of the 2007–08 Serie A season, Inter played Parma away, and two goals from Zlatan Ibrahimović sealed their third consecutive championship. Mancini, however, was sacked soon after due to his previous announcement to leave the club.[27]

Inter supporters during the 2010 UEFA Champions League Final at Santiago Bernabéu. In winning the final, Inter became the first Italian team to win the treble having also won the Serie A title and the Coppa Italia.

On 2 June 2008, Inter appointed former Porto and Chelsea boss José Mourinho as new head coach.[28] In his first season, the Nerazzurri won a Suppercoppa Italiana and a fourth consecutive title, though falling in the Champions League in the first knockout round for a third-straight year, losing to eventual finalist Manchester United. In winning the league title Inter became the first club in the last 60 years to win the title for the fourth consecutive time and joined Torino and Juventus as the only clubs to accomplish this feat, as well as being the first club based outside Turin.

Inter won the 2009–10 Champions League, defeating reigning champions Barcelona in the semi-final before beating Bayern Munich 2–0 in the final with two goals from Diego Milito.[29] Inter also won the 2009–10 Serie A title by two points over Roma, and the 2010 Coppa Italia by defeating the same side 1–0 in the final.[30] This made Inter the first Italian team to win the treble.[31] At the end of the season, Mourinho left the club to manage Real Madrid;[32] he was replaced by Rafael Benítez.

On 21 August 2010, Inter defeated Roma 3–1 and won the 2010 Supercoppa Italiana, their fourth trophy of the year. In December 2010, they claimed the FIFA Club World Cup for the first time after a 3–0 win against TP Mazembe in the final.[33] However, after this win, on 23 December 2010, due to their declining performance in Serie A, the team fired Benítez.[34] He was replaced by Leonardo the following day.[35]

Leonardo started with 30 points from 12 games, with an average of 2.5 points per game, better than his predecessors Benítez and Mourinho. On 6 March 2011, Leonardo set a new Italian Serie A record by collecting 33 points in 13 games; the previous record was 32 points in 13 games made by Fabio Capello in the 2004–05 season. Leonardo led the club to the quarter-finals of the Champions League before losing to Schalke 04, and lead them to Coppa Italia title. At the end of the season, however, he resigned and was followed by new managers Gian Piero Gasperini, Claudio Ranieri and Andrea Stramaccioni, all hired during the following season.

Changes in ownership (2011–2019)

On 1 August 2012, the club announced that Moratti was to sell a minority interest of the club to a Chinese consortium led by Kenneth Huang.[36] On the same day, Inter announced an agreement was formed with China Railway Construction Corporation Limited for a new stadium project, however, the deal with the Chinese eventually collapsed.[37] The 2012–13 season was the worst in recent club history with Inter finishing ninth in Serie A and failing to qualify for any European competitions. Walter Mazzarri was appointed to replace Stramaccioni as the manager for 2013–14 season on 24 May 2013, having ended his tenure at Napoli.[38] He guided the club to fifth in Serie A and to 2014–15 UEFA Europa League qualification.

Inter lining up before a Europa League match against FC Dnipro on 18 September 2014

On 15 October 2013, an Indonesian consortium (International Sports Capital HK Ltd.) led by Erick Thohir, Handy Soetedjo and Rosan Roeslani, signed an agreement to acquire 70% of Inter shares from Internazionale Holding S.r.l.[39][40][41] Immediately after the deal, Moratti’s Internazionale Holding S.r.l. still retained 29.5% of the shares of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.[42] After the deal, the shares of Inter was owned by a chain of holding companies, namely International Sports Capital S.p.A. of Italy (for 70% stake), International Sports Capital HK Limited and Asian Sports Ventures HK Limited of Hong Kong. Asian Sports Ventures HK Limited, itself another intermediate holding company, was owned by Nusantara Sports Ventures HK Limited (60% stake, a company owned by Thohir), Alke Sports Investment HK Limited (20% stake) and Aksis Sports Capital HK Limited (20% stake).

Thohir, whom also co-owned Major League Soccer (MLS) club D.C. United and Indonesia Super League (ISL) club Persib Bandung, announced on 2 December 2013 that Inter and D.C. United had formed strategic partnership.[43] During the Thohir era the club began to modify its financial structure from one reliant on continual owner investment to a more self sustain business model although the club still breached UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations in 2015. The club was fined and received squad reduction in UEFA competitions, with additional penalties suspended in the probation period. During this time, Roberto Mancini returned as the club manager on 14 November 2014, with Inter finishing eighth. Inter finished 2015–2016 season fourth, failing to return to Champions League.

On 6 June 2016, Suning Holdings Group (via a Luxembourg-based subsidiary Great Horizon S.á r.l.) a company owned by Zhang Jindong, co-founder and chairman of Suning Commerce Group, acquired a majority stake of Inter from Thohir’s consortium International Sports Capital S.p.A. and from Moratti family’s remaining shares in Internazionale Holding S.r.l.[44] According to various filings, the total investment from Suning was €270 million.[45] The deal was approved by an extraordinary general meeting on 28 June 2016, from which Suning Holdings Group had acquired a 68.55% stake in the club.[46]

The first season of new ownership, however, started with poor performance in pre-season friendlies. On 8 August 2016, Inter parted company with head coach Roberto Mancini by mutual consent over disagreements regarding the club’s direction.[47] He was replaced by Frank de Boer who was sacked on 1 November 2016 after leading Inter to a 4W–2D–5L record in 11 Serie A games as head coach.[48] The successor, Stefano Pioli, didn’t save the team from getting the worst group result in UEFA competitions in the club’s history.[49] Despite an eight-game winning streak, he and the club parted away before season’s end when it became clear they would finish outside the league’s top three for the sixth consecutive season.[50] On 9 June 2017, former Roma coach Luciano Spalletti was appointed as Inter manager, signing a two-year contract,[51] and eleven months later Inter clinched a UEFA Champions League group stage spot after going six years without Champions League participation thanks to a 3–2 victory against Lazio in the final game of 2017–18 Serie A.[52][53] Due to this success, in August the club extended the contract with Spalletti to 2021.[54]

On 26 October 2018, Steven Zhang was appointed as new president of the club.[55] On 25 January 2019, the club officially announced that LionRock Capital from Hong Kong reached an agreement with International Sports Capital HK Limited, in order to acquire its 31.05% shares in Inter and to become the club’s new minority shareholder.[56] After the 2018–19 Serie A season, despite Inter finishing fourth, Spalletti was sacked.[57] In May 2021, American investment firm Oaktree Capital loaned Inter $336 million to cover losses incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.[58]

Renewed successes (2019–present)

On 31 May 2019, Inter appointed former Juventus and Italian manager Antonio Conte as their new coach, signing a three-year deal.[59] In September 2019, Steven Zhang was elected to the board of the European Club Association.[60] In the 2019–20 Serie A, Inter Milan finished as runner-up as they won 2–0 against Atalanta on the last matchday.[61] They also reached the 2020 UEFA Europa League Final, ultimately losing 3–2 to Sevilla.[62] Following Atalanta’s draw against Sassuolo on 2 May 2021, Internazionale were confirmed as champions for the first time in eleven years, ending Juventus’ run of nine consecutive titles.[63] However, despite securing Serie A glory, Conte left the club by mutual consent on 26 May 2021. The departure was reportedly due to disagreements between Conte and the board over player transfers.[64][65] In June 2021, Simone Inzaghi was appointed as Conte’s replacement.[66] On 22 June 2021, Carlo Cottarelli launched the shareholding of the fans of the Inter Milan club with InterSpac project.[67] On 8 August 2021, Romelu Lukaku was sold to Chelsea F.C. for €115 million, representing the most expensive association football transfer by an Italian football club ever.[68][69]

On 12 January 2022, Inter won the Supercoppa Italiana, defeating Juventus 2–1 at San Siro. After conceding a goal to the opponent, Inter equalised with a penalty scored by Lautaro Martínez, and the match finished 1–1 in regulation time. In the last second of the extra-time, Alexis Sánchez scored the winning goal following a defensive error, giving Inter the first trophy of the season, also Simone Inzaghi’s first trophy as Inter manager.[70] On 11 May 2022, Inter won the Coppa Italia defeating Juventus 4–2 at Stadio Olimpico. After normal time had ended 2–2, with Nicolò Barella and Hakan Çalhanoğlu scoring Inter’s goals, Ivan Perišić’s brace in the extra-time gave Inter the win and the second title of the season.[71] The 2021–22 Serie A campaign saw Inter finish in second place, being the most prolific attacking side with 84 goals.[72] On 18 January 2023, Inter won the Supercoppa Italiana, defeating Milan 3−0 at King Fahd International Stadium, thanks to goals from Federico Dimarco, Edin Džeko, and Lautaro Martinez.[73]

Colours and badge

1928–29 S.S. Ambrosiana in its white and red Crociata shirt

One of the founders of Inter, a painter named Giorgio Muggiani, was responsible for the design of the first Inter logo in 1908. The first design incorporated the letters «FCIM» in the centre of a series of circles that formed the badge of the club. The basic elements of the design have remained constant even as finer details have been modified over the years. Starting at the 1999–2000 season, the original club crest was reduced in size, to give place for the addition of the club’s name and foundation year at the upper and lower part of the logo respectively.

In 2007, the logo was returned to the pre-1999–2000 era. It was given a more modern look with a smaller Scudetto star and lighter color scheme. This version was used until July 2014, when the club decided to undertake a rebranding.[74] The most significant difference between the current and the previous logo is the omission of the star from other media except match kits.[75]

Since its founding in 1908, Inter have almost always worn black and blue stripes, earning them the nickname Nerazzurri. According to the tradition, the colours were adopted to represent the nocturnal sky: in fact, the club was established on the night of 9 March, at 23:30; moreover, blue was chosen by Giorgio Muggiani because he considered it to be the opposite colour to red, worn by the Milan Cricket and Football Club rivals.[76][77]

During the 1928–29 season, however, Inter were forced to abandon their black and blue uniforms. In 1928, Inter’s name and philosophy made the ruling Fascist Party uneasy; as a result, during the same year the 20-year-old club was merged with Unione Sportiva Milanese: the new club was named Società Sportiva Ambrosiana after the patron saint of Milan.[78] The flag of Milan (the red cross on white background) replaced the traditional black and blue.[79] In 1929 the black-and-blue jerseys were restored, and after World War II, when the Fascists had fallen from power, the club reverted to their original name. In 2008, Inter celebrated their centenary with a red cross on their away shirt. The cross is reminiscent of the flag of their city, and they continue to use the pattern on their third kit. In 2014, the club adopted a predominantly black home kit with thin blue pinstripes[80] before returning to a more traditional design the following season.

Animals are often used to represent football clubs in Italy – the grass snake, called Biscione, represents Inter. The snake is an important symbol for the city of Milan, appearing often in Milanese heraldry as a coiled viper with a man in its jaws. The symbol is present on the coat of arms of the House of Sforza (which ruled over Italy from Milan during the Renaissance period), the city of Milan, the historical Duchy of Milan (a 400-year state of the Holy Roman Empire) and Insubria (a historical region the city of Milan falls within). For the 2010–11 season, Inter’s away kit featured the serpent.

-

1908–1928

-

1963–1979

-

1998–2007

-

2007–2014

-

2014–2021

-

2021–present

Stadium

San Siro during an Inter match

The team’s stadium is the 75,923 seat San Siro,[13] officially known as the Stadio Giuseppe Meazza after the former player who represented both Milan and Inter. The more commonly used name, San Siro, is the name of the district where it is located. San Siro has been the home of Milan since 1926, when it was privately built by funding from Milan’s chairman at the time, Piero Pirelli. Construction was performed by 120 workers, and took 13 and a half months to complete. The stadium was owned by the club until it was sold to the city in 1935, and since 1947 it has been shared with Inter, when they were accepted as joint tenant.

The first game played at the stadium was on 19 September 1926, when Inter beat Milan 6–3 in a friendly match. Milan played its first league game in San Siro on 19 September 1926, losing 1–2 to Sampierdarenese. From an initial capacity of 35,000 spectators, the stadium has undergone several major renovations. A major structural renovation was made for the 2016 UEFA Champions League Final while another one took place in late 2021 to host the UEFA Nations League final. The stadium is going to be refurbished again in time for Milano Cortina 2026.[81]

Based on the English model for stadiums, San Siro is specifically designed for football matches, as opposed to many multi-purpose stadiums used in Serie A. It is therefore renowned in Italy for its fantastic atmosphere during matches owing to the closeness of the stands to the pitch.

New Milano Stadium

Since 2012, various proposals and projects by Massimo Moratti have alternated regarding a possible construction of a new Inter stadium.

[82] Between June and July 2019 Inter and A.C. Milan announced the agreement for the construction of a new shared stadium in the San Siro area.[83] In the winter of 2021, Giuseppe Sala, the mayor of Milan, gave the official permission for the construction of the new stadium next to San Siro that will be partially demolished and refunctionalised after the 2026 Olympic Games.[84] In early 2022 Inter and A.C. Milan revealed a «plan B» to relocate the construction of the new Milano stadium in the Greater Milan, away from San Siro area.[85]

Supporters and rivalries

Inter is one of the most supported clubs in Italy, according to an August 2007 research by Italian newspaper La Repubblica.[86] In the early years (until the First World War), Inter fans from the city of Milan were typically middle class, while Milan fans were typically working class.[77] During Massimo Moratti ownership Inter fans were viewed in a moderate left-political eye. At the same time during Silvio Berlusconi reign, A.C. Milan fans were viewed in a moderate/right political eye. Today these divisions are anachronistic.

The traditional ultras group of Inter is Boys San; they hold a significant place in the history of the ultras scene in general due to the fact that they are one of the oldest, being founded in 1969. Politically, one group (Irriducibili) of Inter Ultras are right-wing and this group has good relationships with the Lazio ultras. As well as the main group (apolitical) of Boys San, there are five more significant groups: Viking (apolitical), Irriducibili (right-wing), Ultras (apolitical), Brianza Alcoolica (apolitical) and Imbastisci (left-wing).

Inter’s most vocal fans are known to gather in the Curva Nord, or north curve of the San Siro. This longstanding tradition has led to the Curva Nord being synonymous with the club’s most die-hard supporters, who unfurl banners and wave flags in support of their team.

Scene of a Derby della Madonnina in 1915

Inter have several rivalries, two of which are highly significant in Italian football; firstly, they participate in the intracity Derby della Madonnina with AC Milan; the rivalry has existed ever since Inter splintered off from Milan in 1908.[77] The name of the derby refers to the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose statue atop the Milan Cathedral is one of the city’s main attractions. The match usually creates a lively atmosphere, with numerous (often humorous or offensive) banners unfolded before the match. Flares are commonly present, but they also led to the abandonment of the second leg of the 2004–05 Champions League quarter-final matchup between Milan and Inter on 12 April after a flare thrown from the crowd by an Inter supporter struck Milan keeper Dida on the shoulder.[87]

The other significant rivalry is with Juventus; matches between the two clubs are known as the Derby d’Italia. Up until the 2006 Italian football scandal, which saw Juventus relegated, the two were the only Italian clubs never to have played below Serie A. In the 2000s, Inter developed a rivalry with Roma, who finished as runners-up to Inter in all but one of Inter’s five Scudetto-winning seasons between 2005–06 and 2009–10. The two sides have also contested in five Coppa Italia finals and four Supercoppa Italiana finals since 2006. Other clubs, like Atalanta and Napoli, are also considered among their rivals.[88] Their supporters collectively go by Interisti, or Nerazzurri.[89]

Honours

Inter have won 34 domestic trophies, including the Serie A 19 times, the Coppa Italia eight times and the Supercoppa Italiana seven times. From 2006 to 2010, the club won five successive league titles, equalling the all-time record before 2017, when Juventus won the sixth successive league title.[11] They have won the UEFA Champions League three times: two back-to-back in 1964 and 1965 and then another in 2010; the last completed an unprecedented Italian treble with the Coppa Italia and the Scudetto.[12] The club has also won three UEFA Europa League, two Intercontinental Cup and one FIFA Club World Cup.

Inter has never been relegated from the top flight of Italian football in its entire existence. It is the sole club to have competed in Serie A and its predecessors in every season since its debut in 1909.

Club statistics and records

Javier Zanetti made a record 858 appearances for Internazionale, including 618 in Serie A.

Javier Zanetti holds the records for both total appearances and Serie A appearances for Inter, with 858 official games played in total and 618 in Serie A.

Giuseppe Meazza is Inter’s all-time top goalscorer, with 284 goals in 408 games.[90] Behind him, in second place, is Alessandro Altobelli with 209 goals in 466 games, and Roberto Boninsegna in third place, with 171 goals over 281 games.

Helenio Herrera had the longest reign as Inter coach, with nine years (eight consecutive) in charge, and is the most successful coach in Inter history with three Scudetti, two European Cups, and two Intercontinental Cup wins. José Mourinho, who was appointed on 2 June 2008, completed his first season in Italy by winning the Serie A title and the Supercoppa Italiana; in his second season he won the first «treble» in Italian history: the Serie A, Coppa Italia and the UEFA Champions League.

Players

First-team squad

- As of 31 January 2023[91]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Other players under contract

- As of 2 September 2022

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

- As of 31 January 2023

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Youth teams

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Women team

Notable players

Retired numbers

3 – Giacinto Facchetti, left back, played for Inter 1960–1978 (posthumous honour). The number was retired on 8 September 2006, four days after Facchetti had died from cancer aged 64. The last player to wear the number 3 shirt was Argentinian center back Nicolás Burdisso, who took on the number 16 shirt for the rest of the season.[92]

4 – Javier Zanetti, defensive midfielder, played 858 games for Inter between 1995 and his retirement in the summer of 2014. In June 2014, club chairman Erick Thohir confirmed that Zanetti’s number 4 was to be retired out of respect.[93][94]

Technical staff

- As of 1 July 2021[95]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| Head coach | |

| Vice coach | |

| Technical assistant | |

| Fitness coach | |

| Goalkeeper coach | |

| Functional rehab | |

| Head of match analysis | |

| Match analyst | |

| Fitness data analyst | |

| Head of medical staff | |

| Squad doctor | |

| Physiotherapists coordinator | |

| Physiotherapist | |

| Physiotherapist/Osteopath | |

| Nutritionist |

Chairmen and managers

Chairmen history

Below is a list of Inter chairmen from 1908 until the present day.[96]

Managerial history

Below is a list of Inter coaches from 1909 until the present day.[97]

Corporate

FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. was described as one of the financial «black-holes» among the Italian clubs, which was heavily dependent on the financial contribution from the owner Massimo Moratti.[98][99][100][101] In June 2006, the shirt sponsor and the minority shareholder of the club, Pirelli, sold 15.26% shares of the club to Moratti family, for €13.5 million. The tyre manufacturer retained 4.2%.[102] However, due to several capital increases of Inter, such as a reversed merger with an intermediate holding company, Inter Capital S.r.l. in 2006, which held 89% shares of Inter and €70 million capitals at that time, or issues new shares for €70.8 million in June 2007,[103] €99.9 million in December 2007,[104] €86.6 million in 2008,[105] €70 million in 2009,[106][107] €40 million in 2010 and 2011,[108][109][110][111] €35 million in 2012[37][112] or allowing Thoir subscribed €75 million new shares of Inter in 2013, Pirelli became the third largest shareholders of just 0.5%, as of 31 December 2015.[5] Inter had yet another recapitalization that was reserved for Suning Holdings Group in 2016. In the prospectus of Pirelli’s second IPO in 2017, the company also revealed that the value of the remaining shares of Inter that was owned by Pirelli, was write-off to zero in 2016 financial year. Inter also received direct capital contribution from the shareholders to cover loss which was excluded from issuing shares in the past. (Italian: versamenti a copertura perdite)

Right before the takeover of Thohir, the consolidated balance sheets of «Internazionale Holding S.r.l.» showed the whole companies group had a bank debt of €157 million, including the bank debt of a subsidiary «Inter Brand Srl», as well as the club itself, to Istituto per il Credito Sportivo (ICS), for €15.674 million on the balance sheet at end of 2012–13 financial year.[113] In 2006 Inter sold its brand to the new subsidiary, «Inter Brand S.r.l.», a special purpose entity with a shares capital of €40 million, for €158 million (the deal made Internazionale make a net loss of just €31 million in a separate financial statement[114][115]). At the same time the subsidiary secured a €120 million loan from Banca Antonveneta,[116] which would be repaid in installments until 30 June 2016;[117] La Repubblica described the deal as «doping».[118] In September 2011 Inter secured a loan from ICS by factoring the sponsorship of Pirelli of 2012–13 and 2013–14 season, for €24.8 million, in an interest rate of 3 months Euribor + 1.95% spread.[110] In June 2014 new Inter Group secured €230 million loan[119][120][121] from Goldman Sachs and UniCredit at a new interest rate of 3 months Euribor + 5.5% spread, as well as setting up a new subsidiary to be the debt carrier: «Inter Media and Communication S.r.l.». €200 million of which would be utilized in debt refinancing of the group. The €230million loan, €1 million (plus interests) would be due on 30 June 2015, €45 million (plus interests) would be repaid in 15 installments from 30 September 2015 to 31 March 2019, as well as €184 million (plus interests) would be due on 30 June 2019.[42] In ownership side, the Hong Kong-based International Sports Capital HK Limited, had pledged the shares of Italy-based International Sports Capital S.p.A. (the direct holding company of Inter) to CPPIB Credit Investments for €170 million in 2015, at an interest rate of 8% p.a (due March 2018) to 15% p.a. (due March 2020).[122] ISC repaid the notes on 1 July 2016 after they sold part of the shares of Inter to Suning Holdings Group. However, in the late 2016 the shares of ISC S.p.A. was pledged again by ISC HK to private equity funds of OCP Asia for US$80 million.[123] In December 2017, the club also refinanced its debt of €300 million, by issuing corporate bond to the market, via Goldman Sachs as the bookkeeper, for an interest rate of 4.875% p.a.[124][125][126]

Considering revenue alone, Inter surpassed city rivals in Deloitte Football Money League for the first time, in the 2008–2009 season, to rank in ninth place, one place behind Juventus in eighth place, with Milan in tenth place.[127] In the 2009–10 season, Inter remained in ninth place, surpassing Juventus (10th) but Milan re-took the leading role as the seventh.[128] Inter became the eighth in 2010–2011,[129] but was still one place behind Milan. Since 2011, Inter fell to 11th in 2011–12, 15th in 2012–13, 17th in 2013–14, 19th in 2014–15[130] and 2015–16 season.[131] In 2016–17 season, Inter was ranked 15th in the Money League.[132]

In 2010 Football Money League (2008–09 season), the normalized revenue of €196.5 million were divided up between matchday (14%, €28.2 million), broadcasting (59%, €115.7 million, +7%, +€8 million) and commercial (27%, €52.6 million, +43%).[133] Kit sponsors Nike and Pirelli contributed €18.1 million and €9.3 million respectively to commercial revenues, while broadcasting revenues were boosted €1.6 million (6%) by Champions League distribution. Deloitte expressed the idea that issues in Italian football, particularly matchday revenue issues were holding Inter back compared to other European giants, and developing their own stadia would result in Serie A clubs being more competitive on the world stage.[133]

In 2009–10 season the revenue of Inter was boosted by the sales of Ibrahimović, the treble and the release clause of coach José Mourinho.[134] According to the normalized figures by Deloitte in their 2011 Football Money League, in 2009–10 season, the revenue had increased €28.3 million (14%) to €224.8 million. The ratio of matchday, broadcasting and commercial in the adjusted figures was 17%:62%:21%.[128]

For the 2010–11 season, Serie A clubs started negotiating club TV rights collectively rather than individually.[135] This was predicted to result in lower broadcasting revenues for big clubs such as Juventus[135] and Inter,[133] with smaller clubs gaining from the loss. Eventually the result included an extraordinary income of €13 million from RAI.[108] In 2012 Football Money League (2010–11 season), the normalized revenue was €211.4 million. The ratio of matchday, broadcasting and commercial in the adjusted figures was 16%:58%:26%.[129]

However, combining revenue and cost, in the 2006–07 season they had a net loss of €206 million[104][136] (€112 million extraordinary basis, due to the abolition of non-standard accounting practice of the special amortization fund), followed by a net loss of €148 million in the 2007–08 season,[105] a net loss of €154 million in 2008–09 season,[106][107] a net loss of €69 million in the 2009–10 season,[109][134] a net loss of €87 million in the 2010–11 season,[108][111][137] a net loss of €77 million in the 2011–12 season,[110] a net loss of €80 million in 2012–13 season[37] and a net profit of €33 million in 2013–14 season, due to special income from the establishment of subsidiary Inter Media and Communication.[138] All aforementioned figures were in separate financial statement. Figures from consolidated financial statement were announced since 2014–15 season, which were net losses of €140.4 million (2014–15),[139][140] €59.6 million[140][141] (2015–16 season, before 2017 restatement)[142] and €24.6 million (2016–17).[142][143]

In 2015 Inter and Roma were the only two Italian clubs that were sanctioned by the UEFA due to their breaking of UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations,[144] which was followed by AC Milan which was once barred from returning to European competition in 2018. As a probation to avoid further sanction, Inter agreed to have a three-year aggregate break-even from 2015 to 2018, with the 2015–16 season being allowed to have a net loss of a maximum of €30 million, followed by break-even in the 2016–17 season and onwards. Inter was also fined €6 million plus an additional €14 million in probation.[144]

Inter also made a financial trick in the transfer market in mid-2015, in which Stevan Jovetić and Miranda were signed by Inter on temporary deals plus an obligation to sign outright in 2017, making their cost less in the loan period.[145] Moreover, despite heavily investing in new signings, namely Geoffrey Kondogbia and Ivan Perišić that potentially increased the cost in amortization, Inter also sold Mateo Kovačić for €29 million, making a windfall profit.[145] In November 2018, documents from Football Leaks further revealed that the loan signings such as Xherdan Shaqiri in January 2015, was in fact had inevitable conditions to trigger the outright purchase.[146]

On 21 April 2017, Inter announced that their net loss (FFP adjusted) of 2015–16 season was within the allowable limit of €30 million.[147] However, on the same day UEFA also announced that the reduction of squad size of Inter in European competitions would not be lifted yet, due to partial fulfilment of the targets in the settlement agreement.[148] Same announcement was made by UEFA in June 2018, based on Inter’s 2016–17 season financial result.[149]

In February 2020, Inter Milan sued Major League Soccer (MLS) for trademark infringement, claiming that the term «Inter» is synonymous with its club and no one else.[150]

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor |

|---|---|---|

| 1979–1981 | Puma | |

| 1981–1982 | Inno-Hit | |

| 1982–1986 | Mecsport | Misura |

| 1986–1988 | Le Coq Sportif | |

| 1988–1991 | Uhlsport | |

| 1991–1992 | Umbro | FitGar |

| 1992–1995 | Cesare Fiorucci | |

| 1995–1998 | Pirelli | |

| 1998–2021 | Nike | |

| 2021–2022 |

|

|

| 2022– |

|

See also

- Dynasties in Italian football

- European Club Association

References

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b «Suning Holdings Group acquires majority stake of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» inter.it. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ «Inter, Suning si prende il 68,55%, Moratti lascia dopo 21 anni». gazzetta.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ «LionRock Capital acquires 31.05% of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» inter.it. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b «Annual Report 2015» (PDF). Pirelli. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ List of shareholders on 30 June 2016, document purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A.

- ^ «Steven Zhang named President of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» inter.it. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Inter Milan arrives in Jakarta to prepare for two friendlies». The Jakarta Post. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Grove, Daryl (22 December 2014). «10 Soccer Things You Might Be Saying Incorrectly». Paste. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Cox, Michael (16 March 2023). «From Sporting Lisbon to Athletic Bilbao — why do we get foreign clubs’ names wrong?». The Athletic.

- ^ a b «Italy – List of Champions». RSSSF.

- ^ a b «Inter join exclusive treble club». uefa.com. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b «Struttura». sansirostadium.com (in Italian). San Siro. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ «Is this the greatest derby in world sports?». Theroar.com.au. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ «Best supported clubs who attract more than a million fans every season». talkSPORT. 31 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ «The World’s Most Valuable Soccer Teams». Forbes. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ «Qualcosa di speciale? La patch 105». inter.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ «Storia». FC Internazionale Milano. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ «Helenio Herrera: More than just catenaccio». www.fifa.com. FIFA. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ «Mazzola: Inter is my second family». FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ «La leggenda della Grande Inter» [The legend of the Grande Inter] (in Italian). Inter.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ «La Grande Inter: Helenio Herrera (1910–1997) – «Il Mago»» (in Italian). Sempre Inter. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ «Great Team Tactics: Breaking Down Helenio Herrera’s ‘La Grande Inter’«. Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Fox, Norman (11 November 1997). «Obituary: Helenio Herrera – Obituaries, News». The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Smyth, Rob (17 September 2016). «Ronaldo at 40: Il Fenomeno’s legacy as greatest ever No 9, despite dodgy knees». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Andersson, Astrid (23 April 2007). «Materazzi secures early title for Inter». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano statement». FC Internazionale Milano. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ «Nuovo allenatore: Josè Mourinho all’Inter» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ «Bayern Munich 0–2 Inter Milan». BBC Sport. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ «Jose Mourinho’s Treble-chasing Inter Milan win Serie A». BBC Sport. 16 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Lawrence, Amy (22 May 2010). «Trebles all round to celebrate rarity becoming routine». The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ «Mourinho unveiled as boss of Real». BBC Sport. 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ «TP Mazembe 0–3 Internazionale». ESPN Soccernet. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ «Inter and Benitez separate by mutual agreement». inter.it. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ «Welcome Leonardo! Inter’s new coach». inter.it. 24 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ «Press release: Internazionale Holding S.r.l». FC Internazionale Milano. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ a b c FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2013, PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Comunicato ufficiale di F.C. Internazionale». Inter Official Site. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «Inter Milan Sells 70% Stake To Indonesia’s Erick Thohir At $480M Valuation». Forbes. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano statement». FC Internazionale Milano. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. signs an agreement to open capital to new investors». FC Internazionale Milano. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2014, PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano and D.C. United announce collaborative agreement». FC Internazionale Milano. 2 December 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ «Suning Holdings Group acquires majority stake of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» FC Internazionale Milano. 6 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ «China’s Suning buying majority stake in Inter Milan for $307 million». Reuters. 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ «Assemblea degli Azionisti di FC Internazionale Milano» [FC Internazionale Milano Shareholders’ Meeting] (Press release). FC Internazionale Milano. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano statement». Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano statement». Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ Stefano Scacchi (9 December 2016). «Eder per l’inutile successo dell’Inter passa la sorpresa Hapoel Be’er Sheva». la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 44. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ «FC Internazionale Milano statement». Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ «Inter Milan name Luciano Spalletti as their new boss on a two-year contract». BBC Sport. 9 June 2017.

- ^ PA Sport. «Serie A round-up: Inter Milan beat Lazio to claim final Champions League spot». Sky Sports.

- ^ «Lazio 2–3 Inter Milan». BBC Sport. 20 May 2018.

- ^ «LUCIANO SPALLETTI EXTENDS INTER CONTRACT TO 2021!» (Press release). F.C. Internazionale Milano. 14 August 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ «Steven Zhang named President of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» inter.it. 26 October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «LionRock Capital Acquires 31.05% of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.» (Press release). F.C. Internazionale. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ «Club statement regarding the position of the First Team Head Coach» (Press release). F.C. Internazionale Milano. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ «U.S. Investment Firm Oaktree Capital Signs $336 Million Financing Deal With Serie A Champions FC Inter»

- ^ «OFFICIAL: Inter appoint Conte». football-italia.net. 31 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ «OFFICIAL — Inter President Zhang Elected To ECA Board». SempreInter.com. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «Atalanta 0–2 Inter: Evergreen Young inspires win to secure runner-up spot». Yahoo Sports. 1 August 2020. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ «Inter Milan 5–0 Shakhtar Donetsk». BBC Sport. 17 August 2020.

- ^ «Inter Milan: Italian giants win first Serie A for 11 years». BBC Sport. 2 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ «Antonio Conte leaves Inter Milan after clinching Serie A title -ESPN»

- ^ «Antonio Conte leaves Inter over plan to sell €80m of players this summer». TheGuardian.com. 26 May 2021.

- ^ «Simone Inzaghi appointed Inter Milan head coach — The Athletic»

- ^ «Azionariato popolare: da Ligabue a Bocelli, da Pezzali a Bonolis, ecco chi ha aderito». gazzetta.it. gazzetta.it. 25 June 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ «Inter, il Chelsea offre 115 milioni cash per Lukaku. Si chiude appena c’è il sostituto». gazzetta.it/. gazzetta.it/. 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ «Addio di Lukaku: proprietà e dirigenti, sono tutti responsabili». gazzetta.it. gazzetta.it. 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ «Inter-Juventus 2-1, gol e highlights: ai nerazzurri la Supercoppa, decide Sanchez al 121′» (in Italian).

- ^ «L’Inter vince la Coppa Italia: 4-2 contro la Juve ai supplementari» (in Italian). 11 May 2022.

- ^ «CLASSIFICA SERIE A 2021/2022» (in Italian).

- ^ «La Supercoppa italiana è dell’Inter: 3 a 0 al Milan, gol di Dimarco, Dzeko e Lautaro» (in Italian).

- ^ «Nerazzurri rebranding: new logo, same Inter». Inter.it. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ «Inter rebranding in detail». Inter.it. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ «9 marzo 1908, 43 milanisti fondano l’Inter». ViviMilano.it. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ a b c «AC Milan vs. Inter Milan». FootballDerbies.com. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ «Emeroteca Coni». Emeroteca.coni.it. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ «Ambrosiana S.S 1928». Toffs.com. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Yesilevskiy, Mark (9 July 2014). «Inter Milan 2014/15 home kit». SBNation.com.

- ^ «Viceministro Morelli: «Sul nuovo San Siro avrebbero dovuto decidere prima»«. 4 April 2022.

- ^ «Esclusiva Sindaco S. Donato: «Stadio? Ambito non adeguato. Ci provò Moratti ma…»«. La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ «Milan-Inter avanti decise: «Butteremo giù San Siro e faremo il nuovo stadio». Sala: «Dopo il 2026»«. gazzetta.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ «Nuovo stadio Milan-Inter, Sala: «Sì al San Siro bis seguendo le regole. Per Sesto San Giovanni tempi lunghi»». milano.corriere.it (in Italian). 3 January 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ «Inter CEO admits the clubs could move away from San Siro to new site if delays continue». sempremilan.com. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ «Research: Supporters of football clubs in Italy». La Repubblica (in Italian). August 2007. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ «Milan game ended by crowd trouble». BBC. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ «INTER: gli Ultras avversari – Rangers 1976 Empoli Ultras». Rangers.it. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ «INTERISTI». FC Internazionale Milano. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ «record holders». inter.it. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ «Inter Prima Squadra». FC Internazionale Milano. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ «Inter withdraw the number 3 shirt». Inter.it. 8 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ «Internazionale retire No4 shirt in honour of Javier Zanett». The Guardian.com. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ «Inter make Zanetti vice-president and retire No.4 jersey». Goal.com. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ «Area tecnica». FC Internazionale Milano. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ «i presidenti» (in Italian). inter.it. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ «coaches». inter.it. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ «Moratti, 40 milioni per coprire il buco». La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 9 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ «Why are Russians oiling the wheels of football?». Financial Times. 22 October 2005. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Morrow, Stephen (2003). The People’s Game?: Football, Finance and Society. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 120–123. ISBN 9780230288393. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Calzada, Esteve (2013). Show Me the Money!: How to Make Money Through Sports Marketing. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 9781472903020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ «Annual Report 2006» (PDF). Pirelli & C. S.p.A. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ «Assemblea Straordinaria: comunicato ufficiale» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ a b «Assemblea dei Soci: approvato il bilancio» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 27 December 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2008, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2009, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ a b «Assemblea Soci Inter: approvato il bilancio» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b c FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2011, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ a b «Assemblea Soci Inter: ricavi, oltre 300 milioni» (in Italian). Milan: FC Internazionale Milano. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b c FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2012, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ a b «Assemblea Soci Inter: approvato il bilancio» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 28 October 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ «Assemblea Soci Inter: approvato il bilancio» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 29 October 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Internazionale Holding S.r.l. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2013 (in Italian), PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A.

- ^ «Assemblea: Massimo Moratti Presidente» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 6 November 2006. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2006, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ «All’Inter il primato del deficit: 181,5 milioni». Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Inter Brand S.r.l. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2006, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ «Il «doping» nei conti dei big del pallone perdite complessive oltre i 68 milioni». La Repubblica (in Italian). 9 November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ «Refinancing 230 million euro of Inter Milan debt». nikkei Asian Review. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ «Inter, la rivoluzione di Thohir passa da un’operazione di ingegneria finanziaria. Ma il club si gioca tutto in 5 anni». il sole 24 ore (in Italian). 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ «Inter, buchi in bilancio e tiri Mancini». L’Espresso (in Italian). 21 November 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Filing Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Hong Kong Companies Registry

- ^ «Thohir, prestito di 80 mln dando in pegno la società con le azioni Inter». Calcio e Finanza (in Italian). 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ «Inter lancia Media Bond garantito» (in Italian). ANSA. 11 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Bellinazzo, Marco (11 December 2017). «L’Inter punta a ristrutturare i debiti fino al 2022: lanciato un prestito obbligazionario da 300 milioni». Calcio & business blog. il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ «Comunicato ufficiale». Inter Official Site. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «Real Madrid becomes the first sports team in the world to generate €400m in revenues as it tops Deloitte Football Money League». Deloitte. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b The untouchables Football Money League (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b Fan power Football Money League (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. February 2012. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Top of the table Football Money League (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. January 2016. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Planet Football Football Money League (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. January 2017. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Rising stars Football Money League (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. January 2018. p. 40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Spanish Masters Football Money League» (PDF). Sports Business Group. Deloitte. March 2010. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2010, PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A. (in Italian)

- ^ a b «Premier League v Serie A: TV money». BBC Sport. 21 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2007 (in Italian), PDF purchased from C.C.I.A.A.

- ^ «Inter, 87 milioni di perdite ora si fa dura col fair play». La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Milan. 29 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ «Inter: buco di 103 milioni, sanzione Uefa in arrivo. Thohir: «2–3 anni per risanare»«. La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Milan. 20 October 2014. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

E nel bilancio ratificato oggi è stata resa nota un’operazione straordinaria infragruppo che ha coinvolto la capogruppo e le controllate Inter Brand e Inter Media: per questo motivo nel bilancio di Fc Internazionale risulta un utile di 33 milioni di euro.

- ^ «Inter, perdita consolidata di 140,4 milioni. Bisogna puntare alla Champions». La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio consolidato 2016-06-30 (in Italian). Italian C.C.I.A.A. 2016.

- ^ «Inter, rosso giù a 60 milioni, ma nuovo maxi-prestito dalle banche di 300». La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Milan. 29 October 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio consolidato 2017-06-30 (in Italian). Italian C.C.I.A.A. 2017.

- ^ «Inter, S. Zhang: «Meritiamo l’Europa. Ringrazio Spalletti per il grande lavoro»«. La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Milan. 27 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b «Settlement agreements: details». UEFA. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio 2015-06-30 (in Italian). Italian C.C.I.A.A. 2015.

- ^ «Inter by-passed FFP on Shaqiri». Football Italia. London. 4 November 2018. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ «Inter achieves UEFA break-even target for 2016/17». FC Internazionale Milano. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ «Three clubs exit settlement agreement with CFCB». UEFA. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ «UEFA Club Financial Control Body update on monitoring for 2017/18» (Press release). UEFA. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ Mendola, Nicholas (10 February 2020). «MLS, Inter Miami lose key argument in Inter Milan lawsuit». NBC Sports. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ «A new era begins: Inter announce socios.com as new front-of-shirt partner for 2021/22 season» (Press release). inter.it. 21 July 2021. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ «DIGITALBITS OFFICIAL GLOBAL CRYPTOCURRENCY, ZYTARA OFFICIAL GLOBAL DIGITAL BANKING PARTNER OF INTER IN €85M PRODUCT PARTNERSHIP DEAL». inter.it. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ «New chapter in the partnership between Inter and Lenovo». inter.it. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ «eBay become Inter shirt sleeve sponsor» (Press release). inter.it. 1 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

External links

Wikinews has news related to:

- Official website

(in Italian, English, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Indonesian)

- FC Internazionale Milano Archived 9 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine at Serie A (in English and Italian)

- FC Internazionale Milano at UEFA

Последние темы форума

Сегодня, 16:43 | fc-inter

Трансферы 2023

Сегодня, 14:19 | Adriano1

.jpg.a53130c5c508a801a142e68d21ec1076.thumb.jpg.a7850b88392110bbbf163cf690e719dd.jpg)

Сегодня, 01:26 | DeathCat

Сегодня, 00:32 | fc-inter

.jpeg.dec90bc2e6a2f3e49b5353390e39e388.jpeg.7a4ecb8c9e4ca301a8cb5cdb6861af1f.thumb.jpeg.8162d1ab98224152357f4967b2a27f49.jpeg)

Вчера, 19:07 | Шагрон

.jpeg.dec90bc2e6a2f3e49b5353390e39e388.jpeg.7a4ecb8c9e4ca301a8cb5cdb6861af1f.thumb.jpeg.8162d1ab98224152357f4967b2a27f49.jpeg)

Вчера, 18:48 | Шагрон

Вчера, 13:07 | Biscione

Вчера, 07:54 | fc-inter

Этот пост написан пользователем Sports.ru, начать писать может каждый болельщик (сделать это можно здесь).

Но руководство оптимистично смотрит в будущее.

Итальянский футбол погряз в кризисе: идейном и финансовом. И каждый клуб утопает в собственном болоте проблем. «Ювентус» отлетел на 15 очков из-за махинаций с деньгами и контрактами. «Милан» перестал прогрессировать после скудетто.

«Интер» бьется в конвульсиях из-за долгов. Еще больше ситуацию ухудшают персональные проблемы Стивена Чжана. Все это сильно повлияет на развитие клуба уже в ближайшем будущем. Которое просто необходимо, если «Интер» и дальше хочет выигрывать трофеи.

Что с деньгами «Интера» и что с деньгами Чжана: в марте его ждет суд – достали даже в Италии

На данный момент общий долг «Интера» составляет 275 млн евро. Клуб в январе выпустил облигации на сумму в 468 млн долларов, чтобы частично покрыть задолженность, но этого шага все равно недостаточно, чтобы выйти из кризисной ситуации. Плюс это сильно противоречило планам Чжана, который после ухода Антонио Конте сразу же говорил: «Мы не будем уходить в выпуск облигаций, мы предпочитаем найти решение собственным и более безопасным для клуба путем».

В итоге Чжан не смог сдержать обещание, а выход в плей-офф ЛЧ вызвал внутри клуба больше положительных эмоций из-за призовых за игру в 1/8 финала.

С другой стороны, страдает и сам Чжан, и это действительно глобальная проблема для «Интера». На данный момент Чжан должен 300 млн долларов компании China Construction Bank Asia: 255(чистый долг)+45(просроченная облигация, то есть долговой документ, дающий гарантии истцам).

Если говорить о ходе споров Чжана с китайским банком, то он такой:

• Компания-кредитор подала иск еще в августе-2021. То есть сейчас долг, если вина будет полноценно будет доказана, висит незакрытым почти 2 года.

• Чжан пробовал опротестовать эту сумму, говоря, что это ложь, а никакие деньги никто ему не предоставлял. Но еще в июле верховный суд Гонконга отклонил апелляцию и принял сторону China Construction Bank Asia.

• В октябре истец снова потребовал от Чжана выплаты 300 млн долларов. Тогда Чжан сказал, что намерен бороться до конца в этом судебном деле.

Что произошло сейчас – пресса начала обсуждать трехмесячное тюремное заключение Чжана. Такой поворот возможен, если прокуратура установит, что у Чжана была требуемая сумма, но он отказался от выплат. И, кстати, компания China Construction Bank поступила максимально предусмотрительно, подав в суд на Чжана в Китае (там преследование может распространиться по всей стране), Майами (у Стивена там недвижимость) и Милане (тут понятна причина).

Дело осложняет договор от 2015 года между Китаем и Италией. Это соглашение об экстрадиции и взаимной помощи по уголовным делам. Так что если Чжана отправят в тюрьму в Милане, то, возможно, его сразу же передадут Китаю. Пока до тюрьмы и реальных сроков еще далеко. Суду предстоит доказать факт именно наличия этих средств (300 млн) у Чжана. Первое заседание намечено на 8 марта и пройдет в Милане – до этого пока трудно говорить, понесет ли он какое-либо наказание за просроченный платеж.

Есть ли у «Интера» выход из этой ситуации? Да, есть, но он зависит только от прибытия новых владельцев. Чжан и Suning Group уже выписали мандат международной юридической фирме Latham and Watkins на поиск новых владельцев. Пока что эти поиски не были успешными. В основном они проходили в США, где у действующего владельца «Интера» много друзей и партнеров по бизнесу.

У перестройки «Интера» несколько этапов. Первые стартуют следующим летом

Первый этап – большие изменения в составе команды. Здесь информация от GdS.

Уходят:

• Милан Шкриньяр. Тут все ясно, экс-капитан не продлил контракт и уйдет в «ПСЖ».

• Марцело Брозович. Интереса по нему особо нет, а зарплата кусающаяся. Плюс в этом сезоне Брозо далек от своей лучшей формы, поэтому есть вопросы, удачной ли станет его продажа. Но руководство больше не считает его неприкасаемым игроком.

Добавьте к списку уходящих Хоакина Корреа (10-20 млн), который окончательно потерял форму, и Дензела Дюмфриса (40-50 млн), к которому есть предметный интерес из АПЛ.

Возможно, придут:

• Чаглар Сеюнджю. Свободный агент. Личка чуть больше 2 млн евро в год. Кажется, косячнее Шкриньяра, к тому же за ним приглядывал «Атлетико». Кстати, про Сеюнджю была история еще летом-2021, Аузилио летал в Англию, а его самолет приземлился в аэропорту Лестера. Тогда журналисты спрашивали о цели визита в Англию, а Пьеро отмахнулся: «Вы много говорите о новом защитнике для «Интера». Так вот, я активно занимаюсь его поисками».

И еще немного о конкуренции за Сеюнджю. За «Интер» же играет Хакан, его партнер по сборной – важное преимущество, если клуб действительно ввяжется в гонку за турецкого защитника.

• Роберто Перейра. Свободный агент. Личка в районе млн евро в год. Не очень понятно, зачем туго перестраивающемуся «Интеру» 32-летний аргентинец.

• Франк Кессье. Вряд ли он придет в «Интер» на постоянной основе. В «Барсе» он получает 10 млн в год – там боссы не дураки и не богатеи, чтобы разбивать оклад на две части: одну – для себя, другую для «Интера». А полноценно зарплату Кессье «Интер» не потянет самостоятельно.

GdS пишет, что «Интер» рассчитывает на пару вербальных факторов в борьбе за Кессье. Первый – его любовь к Италии. Октябрьское интервью: «Мне нравится город [Барселона], но я еще не привык к нему, как к Милану. Для меня это лучший город на земле, при всем уважении к Каталонии». Второй – агент Хакан Чалханоглу, который до сих пор поддерживает связь с Кессье и, по данным розовой газеты, говорит, как прекрасно жить в «Интере».

• Крис Смоллинг. Свободный агент. Получает в «Роме» 4 млн в год. Думаю, у «Интера» попросит не меньше.

Добавьте сюда Маркуса Тюрама (0 евро), к которому давно присматривается Маротта, и Родриго Бекао (примерно 10 млн за трансфер), которого медиа называют вероятным сменщиком Шкриньяра. В шорт-листе «Интера» есть Джорджо Скальвини из «Аталанты», но сумма в 40 млн евро слишком большая для клуба.

Второй этап перестройки – вероятная смена тренера. Позиция Симоне Индзаги слишком шатается и во многом зависит от попадания в зону ЛЧ по итогам сезона. Но та же GdS писала, что сотрудничество с Индзаги может закончиться, если у руководства будет подходящий вариант для замены. Месяц назад испанские источники говорили об уходе Диего Симеоне из «Атлетико» – он неоднократно говорил, что мечтает о возвращении в «Интер». Но Симеоне опроверг эти слухи и заявил, что хочет отработать свой контракт с клубом до конца.

Другой вариант – Роберто Де Дзерби. Мэтт Лоу из The Telegraph написал, что Де Дзерби своей работой в «Брайтоне» привлек внимание некоторых топ-клубов Европы. В это число входит и «Интер». Трансфер Де Дзерби может состояться уже летом.

Третий – вероятная смена владельцев. Несколько итальянских медиа уже писали: если раньше Чжан хотел сохранить «Интер», то сейчас, когда проблем стало больше, он думает о полноценной продаже клуба. Оптимизм в фанатах «Интера» говорит, что финансовая ситуация резко изменится в положительную сторону с приходом новых управленцев.

***

«Изменения – это нормально. Любой клуб должен меняться и совершенствоваться. Важно лишь наблюдать за этим процессом и следить, чтобы ничего не выходило из-под контроля. «Интер» тоже меняется. У нас есть проблемы, но мы завоевываем трофеи и делаем это в последнее время чаще конкурентов, несмотря ни на что. Будем надеяться, что в ближайшее время мы вместе с членами остальной команды вернем «Интер» на топ-уровень по меркам Европы».

Беппе Маротта смел в своих прогнозах – но этому «Интер» однозначно нужны решительность и смелость для приятных перемен.

Фото: телеграм-канал «Интер»

Подписывайтесь на телеграм-канал автора об «Интере» и будьте в курсе последних и важнейших новостей в жизни клуба

FC INTERNAZIONALE MILANO

President

Zhang Kangyang

Vice president

Javier Zanetti

Board of Directors

Zhang Kangyang, Alessandro Antonello, Giuseppe Marotta,

Yang Yang, Zhu Qing, Zhou Bin, Ying Ruohan,

Daniel Kar Keung Tseung, Carlo Marchetti, Amedeo Carassai

Board of Auditors, Permanent Auditors

Alessandro Padula, Roberto Cassader, Simone Biagiotti

Chief Executive Officer Corporate

Alessandro Antonello

Chief Executive Officer Sport

Giuseppe Marotta

Chief Sport Officer

Piero Ausilio

Chief Revenue Officer

Luca Danovaro

Chief Communications Officer

Matteo Pedinotti

Chief Financial Officer

Andrea Accinelli

Chief People Officer

Lionel Sacchi

Chief Operating Officer

Mark Van Huuksloot

INTER FUTURA

President

Maria Carlotta Moratti

Vice president

Alessandro Antonello

Board of Directors

Angelomario Moratti, Giovanni Moratti,

Luca Danovaro, Barbara Biggi, Cesare Scalia

В минувшем сезоне миланский клуб впервые за 11 лет стал чемпионом Италии. Антонио Конте, возглавлявший нерадзурри на протяжении двух лет, покинул свой пост из-за несогласия с политикой руководства.

Итальянский тренер Симоне Индзаги назначен главным тренером миланского «Интера». Об этом сообщается на сайте клуба.

Соглашение 45-летнего специалиста с чёрно-синими рассчитано на два года.

На посту главного тренера «Интера» Индзаги сменил Антонио Конте, возглавлявшего команду на протяжении двух лет и ушедшего в отставку из-за несогласия с политикой руководства. В прошлом сезоне нерадзурри впервые за 11 лет стали чемпионами Италии.

Индзаги с 2016 года возглавлял римский «Лацио», который покинул по окончании сезона. Со столичным клубом он выиграл Кубок Италии и два Суперкубка страны. В Серии А 2020/21 бело-голубые заняли шестое место, не попав в Лигу чемпионов.