| Al-Qaeda | |

|---|---|

| القاعدة | |

Flag used by various al-Qaeda factions |

|

| Leaders |

|

| Dates of operation | 11 August 1988 – present |

| Group(s) |

|

| Active regions | Worldwide Current territorial control: Mali, Somalia,[1] Yemen[2] |

| Ideology |

|

| Size |

|

| Allies |

|

| Opponents |

|

| Battles and wars |

|

| Designated as a terrorist group by | See below |

|

Preceded by |

Al-Qaeda (; Arabic: القاعدة, romanized: al-Qāʿida, lit. ‘the Base’, IPA: [ælqɑːʕɪdɐ]) is a Sunni pan-Islamist militant organization led by Salafi jihadists who self-identify as a vanguard spearheading a global Islamist revolution to unite the Muslim world under a supra-national Islamic state known as the Caliphate.[67][68] Its members are mostly composed of Arabs, but also include other peoples.[69] Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military targets in various countries, including the 1998 United States embassy bombings, the 2001 September 11 attacks, and the 2002 Bali bombings; it has been designated as a terrorist group by the United Nations Security Council,[70] the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union, and various countries around the world.

The organization was founded in a series of meetings held in Peshawar during 1988, attended by Abdullah Azzam, Osama bin Laden, Muhammad Atef, Ayman al-Zawahiri and other veterans of the Soviet–Afghan War.[71] Building upon the networks of Maktab al-Khidamat, the founding members decided to create an organization named «Al-Qaeda» to serve as a «vanguard» for jihad.[71][72] Following the withdrawal of the Soviets in 1989, bin Laden offered mujahideen support to Saudi Arabia in the Gulf War in 1990–1991. His offer was rebuffed by the Saudi government, which instead sought the aid of the United States. The stationing of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia prompted bin Laden to declare a jihad against the House of Saud, whom he condemned as takfir (apostates from Islam), and against the US. During 1992–1996, al-Qaeda established its headquarters in Sudan until it was expelled in 1996. It shifted its base to the Taliban-ruled Afghanistan and later expanded to other parts of the world, primarily in the Middle East and South Asia.

In 1996 and 1998, bin Laden issued two fatāwā calling for U.S. troops to leave Saudi Arabia. Al-Qaeda conducted the 1998 United States embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, which killed 224 people. The U.S. retaliated by launching Operation Infinite Reach, against al-Qaeda targets in Afghanistan and Sudan. In 2001, al-Qaeda carried out the September 11 attacks, resulting in nearly 3,000 fatalities, substantial long-term health consequences and damaging global economic markets. The U.S. launched the war on terror in response and invaded Afghanistan to depose the Taliban and destroy al-Qaeda. In 2003, a U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq, overthrowing the Ba’athist regime which it

wrongly accused of having ties with al-Qaeda. In 2004, al-Qaeda launched its Iraqi regional branch. After pursuing him for almost a decade, the U.S. military killed bin Laden in Pakistan in May 2011.

Al-Qaeda members believe a Judeo-Christian alliance (led by the United States) is conspiring to be at war against Islam and destroy Islam.[73][74] As Salafist jihadists, members of Al-Qaeda believe that killing non-combatants is religiously sanctioned. Al-Qaeda also opposes what it regards as man-made laws, and wants to replace them exclusively with a strict form of sharīʿa (Islamic religious law, which is perceived as divine law).[75] It characteristically organizes attacks such as suicide attacks and simultaneous bombing of several targets.[76] Al-Qaeda’s Iraq branch, which later morphed into the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, was responsible for numerous sectarian attacks against Shias during its Iraqi insurgency.[77][78] Al-Qaeda ideologues envision the violent removal of all foreign and secular influences in Muslim countries, which it denounces as corrupt deviations.[14][79][80][81] Following the death of bin Laden in 2011, al-Qaeda vowed to avenge his killing. The group was then led by Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri until his death in 2022. As of 2021, it has reportedly suffered from a deterioration of central command over its regional operations.[82]

Organization

Al-Qaeda only indirectly controls its day-to-day operations. Its philosophy calls for the centralization of decision making, while allowing for the decentralization of execution.[83] The top leaders of Al-Qaeda have defined the organization’s ideology and guiding strategy, and they have also articulated simple and easy-to-receive messages. At the same time, mid-level organizations were given autonomy, but they had to consult with top management before large-scale attacks and assassinations. Top management included the shura council as well as committees on military operations, finance, and information sharing. Through the information committees of Al-Qaeda, Zawahiri placed special emphasis on communicating with his groups.[84] However, after the war on terror, Al-Qaeda’s leadership has become isolated. As a result, the leadership has become decentralized, and the organization has become regionalized into several Al-Qaeda groups.[85][86]

Many terrorism experts do not believe that the global jihadist movement is driven at every level by Al-Qaeda’s leadership. However, bin Laden held considerable ideological sway over some Muslim extremists before his death. Experts argue that Al-Qaeda has fragmented into a number of disparate regional movements, and that these groups bear little connection with one another.[87]

This view mirrors the account given by Osama bin Laden in his October 2001 interview with Tayseer Allouni:

this matter isn’t about any specific person and … is not about the al-Qa’idah Organization. We are the children of an Islamic Nation, with Prophet Muhammad as its leader, our Lord is one … and all the true believers [mu’mineen] are brothers. So the situation isn’t like the West portrays it, that there is an ‘organization’ with a specific name (such as ‘al-Qa’idah’) and so on. That particular name is very old. It was born without any intention from us. Brother Abu Ubaida … created a military base to train the young men to fight against the vicious, arrogant, brutal, terrorizing Soviet empire … So this place was called ‘The Base’ [‘Al-Qa’idah’], as in a training base, so this name grew and became. We aren’t separated from this nation. We are the children of a nation, and we are an inseparable part of it, and from those public demonstrations which spread from the far east, from the Philippines to Indonesia, to Malaysia, to India, to Pakistan, reaching Mauritania … and so we discuss the conscience of this nation.[88]

As of 2010 however, Bruce Hoffman saw Al-Qaeda as a cohesive network that was strongly led from the Pakistani tribal areas.[87]

Affiliates

Al-Qaeda has the following direct affiliates:

- Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)

- Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS)

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

- Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM)

- Al-Qaeda in Bosnia and Herzegovina[89]

- Imam Shamil Battalion

- Tawhid al-Jihad (Gaza Strip)

- Kurdistan Brigades[90]

- Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades

- Tanzim Qaedat al-Jihad

- Al-Qaeda in the Sinai Peninsula

- Hurras al-Din

The following are presently believed to be indirect affiliates of Al-Qaeda:

- Caucasus Emirate (factions)

- Fatah al-Islam[91]

- Islamic Jihad Union[92]

- Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan

- Jaish-e-Mohammed[93]

- Jemaah Islamiyah[94]

- Lashkar-e-Taiba[95]

- Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group[96]

Al-Qaeda’s former affiliates include the following:

- Abu Sayyaf (pledged allegiance to ISIL in 2014[97])

- Al-Mourabitoun (joined JNIM in 2017[98])

- Al-Qaeda in Iraq (became the Islamic State of Iraq, which later seceded from al-Qaeda and became ISIL)

- Al-Qaeda in the Lands Beyond the Sahel (inactive since 2015[99])

- Ansar al-Islam (majority merged with ISIL in 2014)

- Ansar Dine (joined JNIM in 2017[98])

- Islamic Jihad of Yemen (became AQAP)

- Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (merged with Al-Mulathameen to form Al-Mourabitoun in 2013)

- Rajah Sulaiman movement[100]

- Al-Nusra Front (dissolved in 2017, merged with other groups to form Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and split ties)

Leadership

Osama bin Laden (1988–May 2011)

Osama bin Laden (left) and Ayman al-Zawahiri (right) photographed in 2001

Osama bin Laden served as the emir of Al-Qaeda from the organization’s founding in 1988 until his assassination by US forces on May 1, 2011.[101] Atiyah Abd al-Rahman was alleged to be second in command prior to his death on August 22, 2011.[102]

Bin Laden was advised by a Shura Council, which consists of senior Al-Qaeda members.[103] The group was estimated to consist of 20–30 people.

After May 2011

Ayman al-Zawahiri had been Al-Qaeda’s deputy emir and assumed the role of emir following bin Laden’s death. Al-Zawahiri replaced Saif al-Adel, who had served as interim commander.[104]

On June 5, 2012, Pakistani intelligence officials announced that al-Rahman’s alleged successor as second in command, Abu Yahya al-Libi, had been killed in Pakistan.[105]

Nasir al-Wuhayshi was alleged to have become Al-Qaeda’s overall second in command and general manager in 2013. He was concurrently the leader of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) until he was killed by a US airstrike in Yemen in June 2015.[106] Abu Khayr al-Masri, Wuhayshi’s alleged successor as the deputy to Ayman al-Zawahiri, was killed by a US airstrike in Syria in February 2017.[107] Al Qaeda’s next alleged number two leader, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, was killed by Israeli agents. His pseudonym was Abu Muhammad al-Masri, who was killed in November 2020 in Iran. He was involved in the 1998 bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.[108]

Al-Qaeda’s network was built from scratch as a conspiratorial network which drew upon the leadership of a number of regional nodes.[109] The organization divided itself into several committees, which include:

- The Military Committee, which is responsible for training operatives, acquiring weapons, and planning attacks.

- The Money/Business Committee, which funds the recruitment and training of operatives through the hawala banking system. US-led efforts to eradicate the sources of «terrorist financing»[110] were most successful in the year immediately following the September 11 attacks.[111] Al-Qaeda continues to operate through unregulated banks, such as the 1,000 or so hawaladars in Pakistan, some of which can handle deals of up to US$10 million.[112] The committee also procures false passports, pays Al-Qaeda members, and oversees profit-driven businesses.[113] In the 9/11 Commission Report, it was estimated that Al-Qaeda required $30 million per year to conduct its operations.

- The Law Committee reviews Sharia law, and decides upon courses of action conform to it.

- The Islamic Study/Fatwah Committee issues religious edicts, such as an edict in 1998 telling Muslims to kill Americans.

- The Media Committee ran the now-defunct newspaper Nashrat al Akhbar (English: Newscast) and handled public relations.

- In 2005, Al-Qaeda formed As-Sahab, a media production house, to supply its video and audio materials.

After Al-Zawahiri (2022 — present)

Al-Zawahiri was killed on July 31, 2022 in a drone strike in Afghanistan.[114] In February 2023, a report from the United Nations, based on member state intelligence, concluded that de-facto leadership of Al-Qaeda had passed to Saif al-Adel, who was operating out of Iran. Adel, a former Egyptian army officer, became a military instructor Al-Qaeda camps in 1990s and was known for his involvement in the Battle of Mogadishu. The report stated that al-Adel’s leadership could not officially be declared by al-Qaeda because of «political sensitivities» of Afghan government in acknowledging the death of Al-Zawahiri as well as due to «theological and operational» challenges posed by the location of al-Adel in Iran.[115][116]

Command structure

Most of Al Qaeda’s top leaders and operational directors were veterans who fought against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Osama bin Laden and his deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, were the leaders who were considered the operational commanders of the organization.[117] Nevertheless, Al-Qaeda is not operationally managed by Ayman al-Zawahiri. Several operational groups exist, which consult with the leadership in situations where attacks are in preparation.[118] Al-Qaeda central (AQC) is a conglomerate of expert committees, each in supervision of distinct tasks and objectives. Its membership is mostly composed of Egyptian Islamist leaders who participiated in the anti-communist Afghan Jihad. Assisting them are hundreds of Islamic field operatives and commanders, based in various regions of the Muslim World. The central leadership assumes control of the doctrinal approach and overall propaganda campaign; while the regional commanders were empowered with independence in military strategy and political maneuvering. This novel heirarchy made it possible for the organisation to launch wide-range offensives.[119]

When asked in 2005 about the possibility of Al-Qaeda’s connection to the July 7, 2005 London bombings, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair said: «Al-Qaeda is not an organization. Al-Qaeda is a way of working … but this has the hallmark of that approach … Al-Qaeda clearly has the ability to provide training … to provide expertise … and I think that is what has occurred here.»[120] On August 13, 2005, The Independent newspaper, reported that the July 7 bombers had acted independently of an Al-Qaeda mastermind.[121]

Nasser al-Bahri, who was Osama bin Laden’s bodyguard for four years in the run-up to 9/11 wrote in his memoir a highly detailed description of how the group functioned at that time. Al-Bahri described Al-Qaeda’s formal administrative structure and vast arsenal.[122] However, the author Adam Curtis argued that the idea of Al-Qaeda as a formal organization is primarily an American invention. Curtis contended the name «Al-Qaeda» was first brought to the attention of the public in the 2001 trial of bin Laden and the four men accused of the 1998 US embassy bombings in East Africa. Curtis wrote:

The reality was that bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri had become the focus of a loose association of disillusioned Islamist militants who were attracted by the new strategy. But there was no organization. These were militants who mostly planned their own operations and looked to bin Laden for funding and assistance. He was not their commander. There is also no evidence that bin Laden used the term «al-Qaeda» to refer to the name of a group until after September 11 attacks, when he realized that this was the term the Americans had given it.[123]

During the 2001 trial, the US Department of Justice needed to show that bin Laden was the leader of a criminal organization in order to charge him in absentia under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. The name of the organization and details of its structure were provided in the testimony of Jamal al-Fadl, who said he was a founding member of the group and a former employee of bin Laden.[124] Questions about the reliability of al-Fadl’s testimony have been raised by a number of sources because of his history of dishonesty, and because he was delivering it as part of a plea bargain agreement after being convicted of conspiring to attack US military establishments.[125][126] Sam Schmidt, a defense attorney who defended al-Fadl said:

There were selective portions of al-Fadl’s testimony that I believe was false, to help support the picture that he helped the Americans join together. I think he lied in a number of specific testimony about a unified image of what this organization was. It made al-Qaeda the new Mafia or the new Communists. It made them identifiable as a group and therefore made it easier to prosecute any person associated with al-Qaeda for any acts or statements made by bin Laden.[123]

Field operatives

The number of individuals in the group who have undergone proper military training, and are capable of commanding insurgent forces, is largely unknown. Documents captured in the raid on bin Laden’s compound in 2011 show that the core Al-Qaeda membership in 2002 was 170.[127] In 2006, it was estimated that Al-Qaeda had several thousand commanders embedded in 40 countries.[128] As of 2009, it was believed that no more than 200–300 members were still active commanders.[129]

According to the 2004 BBC documentary The Power of Nightmares, Al-Qaeda was so weakly linked together that it was hard to say it existed apart from bin Laden and a small clique of close associates. The lack of any significant numbers of convicted Al-Qaeda members, despite a large number of arrests on terrorism charges, was cited by the documentary as a reason to doubt whether a widespread entity that met the description of Al-Qaeda existed.[130] Al-Qaeda’s commanders, as well as its sleeping agents, are hiding in different parts of the world to this day. They are mainly hunted by the American and Israeli secret services.

Insurgent forces

According to author Robert Cassidy, Al-Qaeda maintains two separate forces which are deployed alongside insurgents in Iraq and Pakistan. The first, numbering in the tens of thousands, was «organized, trained, and equipped as insurgent combat forces» in the Soviet–Afghan war.[128] The force was composed primarily of foreign mujahideen from Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Many of these fighters went on to fight in Bosnia and Somalia for global jihad. Another group, which numbered 10,000 in 2006, live in the West and have received rudimentary combat training.[128]

Other analysts have described Al-Qaeda’s rank and file as being «predominantly Arab» in its first years of operation, but that the organization also includes «other peoples» as of 2007.[131] It has been estimated that 62 percent of Al-Qaeda members have a university education.[132] In 2011 and the following year, the Americans successfully settled accounts with Osama bin Laden, Anwar al-Awlaki, the organization’s chief propagandist, and Abu Yahya al-Libi’s deputy commander. The optimistic voices were already saying it was over for Al-Qaeda. Nevertheless, it was around this time that the Arab Spring greeted the region, the turmoil of which came great to Al-Qaeda’s regional forces. Seven years later, Ayman al-Zawahiri became arguably the number one leader in the organization, implementing his strategy with systematic consistency. Tens of thousands loyal to Al-Qaeda and related organizations were able to challenge local and regional stability and ruthlessly attack their enemies in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Europe and Russia alike. In fact, from Northwest Africa to South Asia, Al-Qaeda had more than two dozen «franchise-based» allies. The number of Al-Qaeda militants was set at 20,000 in Syria alone, and they had 4,000 members in Yemen and about 7,000 in Somalia. The war was not over.[133]

In 2001, Al-Qaeda had around 20 functioning cells and 70,000 insurgents spread over sixty nations.[134] According to latest estimates, the number of active-duty soldiers under its command and allied militias have risen to approximately 250,000 by 2018.[135]

Financing

Al-Qaeda usually does not disburse funds for attacks, and very rarely makes wire transfers.[136] In the 1990s, financing came partly from the personal wealth of Osama bin Laden.[137] Other sources of income included the heroin trade and donations from supporters in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and other Islamic Gulf states.[137] A WikiLeaks-released 2009 internal US government cable stated that «terrorist funding emanating from Saudi Arabia remains a serious concern.»[138]

Among the first pieces of evidence regarding Saudi Arabia’s support for Al-Qaeda was the so-called «Golden Chain», a list of early Al-Qaeda funders seized during a 2002 raid in Sarajevo by Bosnian police.[139] The hand-written list was validated by Al-Qaeda defector Jamal al-Fadl, and included the names of both donors and beneficiaries.[139][140] Osama bin-Laden’s name appeared seven times among the beneficiaries, while 20 Saudi and Gulf-based businessmen and politicians were listed among the donors.[139] Notable donors included Adel Batterjee, and Wael Hamza Julaidan. Batterjee was designated as a terror financier by the US Department of the Treasury in 2004, and Julaidan is recognized as one of Al-Qaeda’s founders.[139]

Documents seized during the 2002 Bosnia raid showed that Al-Qaeda widely exploited charities to channel financial and material support to its operatives across the globe.[141] Notably, this activity exploited the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO) and the Muslim World League (MWL). The IIRO had ties with Al-Qaeda associates worldwide, including Al-Qaeda’s deputy Ayman al Zawahiri. Zawahiri’s brother worked for the IIRO in Albania and had actively recruited on behalf of Al-Qaeda.[142] The MWL was openly identified by Al-Qaeda’s leader as one of the three charities Al-Qaeda primarily relied upon for funding sources.[142]

Allegations of Qatari support

Several Qatari citizens have been accused of funding Al-Qaeda. This includes Abd Al-Rahman al-Nuaimi, a Qatari citizen and a human-rights activist who founded the Swiss-based non-governmental organization (NGO) Alkarama. On December 18, 2013, the US Treasury designated Nuaimi as a terrorist for his activities supporting Al-Qaeda.[143] The US Treasury has said Nuaimi «has facilitated significant financial support to Al-Qaeda in Iraq, and served as an interlocutor between Al-Qaeda in Iraq and Qatar-based donors».[143]

Nuaimi was accused of overseeing a $2 million monthly transfer to Al-Qaeda in Iraq as part of his role as mediator between Iraq-based Al-Qaeda senior officers and Qatari citizens.[143][144] Nuaimi allegedly entertained relationships with Abu-Khalid al-Suri, Al-Qaeda’s top envoy in Syria, who processed a $600,000 transfer to Al-Qaeda in 2013.[143][144] Nuaimi is also known to be associated with Abd al-Wahhab Muhammad ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Humayqani, a Yemeni politician and founding member of Alkarama, who was listed as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) by the US Treasury in 2013.[145] The US authorities claimed that Humayqani exploited his role in Alkarama to fundraise on behalf of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[143][145] A prominent figure in AQAP, Nuaimi was also reported to have facilitated the flow of funding to AQAP affiliates based in Yemen. Nuaimi was also accused of investing funds in the charity directed by Humayqani to ultimately fund AQAP.[143] About ten months after being sanctioned by the US Treasury, Nuaimi was also restrained from doing business in the UK.[146]

Another Qatari citizen, Kalifa Mohammed Turki Subayi, was sanctioned by the US Treasury on June 5, 2008, for his activities as a «Gulf-based Al-Qaeda financier». Subayi’s name was added to the UN Security Council’s Sanctions List in 2008 on charges of providing financial and material support to Al-Qaeda senior leadership.[144][147] Subayi allegedly moved Al-Qaeda recruits to South Asia-based training camps.[144][147] He also financially supported Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, a Pakistani national and senior Al-Qaeda officer who is believed to be the mastermind behind the September 11 attack according to the September 11 Commission report.[148]

Qataris provided support to Al-Qaeda through the country’s largest NGO, the Qatar Charity. Al-Qaeda defector al-Fadl, who was a former member of Qatar Charity, testified in court that Abdullah Mohammed Yusef, who served as Qatar Charity’s director, was affiliated to Al-Qaeda and simultaneously to the National Islamic Front, a political group that gave Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden harbor in Sudan in the early 1990s.[140]

It was alleged that in 1993 Bin Laden was using Middle East based Sunni charities to channel financial support to Al-Qaeda operatives overseas. The same documents also report Bin Laden’s complaint that the failed assassination attempt of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak had compromised the ability of Al-Qaeda to exploit charities to support its operatives to the extent it was capable of before 1995.[citation needed]

Qatar financed Al-Qaeda’s enterprises through Al-Qaeda’s former affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra. The funding was primarily channeled through kidnapping for ransom.[149] The Consortium Against Terrorist Finance (CATF) reported that the Gulf country has funded al-Nusra since 2013.[149] In 2017, Asharq Al-Awsat estimated that Qatar had disbursed $25 million in support of al-Nusra through kidnapping for ransom.[150] In addition, Qatar has launched fundraising campaigns on behalf of al-Nusra. Al-Nusra acknowledged a Qatar-sponsored campaign «as one of the preferred conduits for donations intended for the group».[151][152]

Strategy

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2016) |

In the disagreement over whether Al-Qaeda’s objectives are religious or political, Mark Sedgwick describes Al-Qaeda’s strategy as political in the immediate term but with ultimate aims that are religious.[153]

On March 11, 2005, Al-Quds Al-Arabi published extracts from Saif al-Adel’s document «Al Qaeda’s Strategy to the Year 2020».[3][154] Abdel Bari Atwan summarizes this strategy as comprising five stages to rid the Ummah from all forms of oppression:

- Provoke the United States and the West into invading a Muslim country by staging a massive attack or string of attacks on US soil that results in massive civilian casualties.

- Incite local resistance to occupying forces.

- Expand the conflict to neighboring countries and engage the US and its allies in a long war of attrition.

- Convert Al-Qaeda into an ideology and set of operating principles that can be loosely franchised in other countries without requiring direct command and control, and via these franchises incite attacks against the US and countries allied with the US until they withdraw from the conflict, as happened with the 2004 Madrid train bombings, but which did not have the same effect with the July 7, 2005 London bombings.

- The US economy will finally collapse by 2020, under the strain of multiple engagements in numerous places. This will lead to a collapse in the worldwide economic system, and lead to global political instability. This will lead to a global jihad led by Al-Qaeda, and a Wahhabi Caliphate will then be installed across the world.

Atwan noted that, while the plan is unrealistic, «it is sobering to consider that this virtually describes the downfall of the Soviet Union.»[3]

According to Fouad Hussein, a Jordanian journalist and author who has spent time in prison with Al-Zarqawi, Al Qaeda’s strategy consists of seven phases and is similar to the plan described in Al Qaeda’s Strategy to the year 2020. These phases include:[155]

- «The Awakening.» This phase was supposed to last from 2001 to 2003. The goal of the phase is to provoke the United States to attack a Muslim country by executing an attack that kills many civilians on US soil.

- «Opening Eyes.» This phase was supposed to last from 2003 to 2006. The goal of this phase was to recruit young men to the cause and to transform the Al-Qaeda group into a movement. Iraq was supposed to become the center of all operations with financial and military support for bases in other states.

- «Arising and Standing up», was supposed to last from 2007 to 2010. In this phase, Al-Qaeda wanted to execute additional attacks and focus their attention on Syria. Hussein believed other countries in the Arabian Peninsula were also in danger.

- Al-Qaeda expected a steady growth among their ranks and territories due to the declining power of the regimes in the Arabian Peninsula. The main focus of attack in this phase was supposed to be on oil suppliers and cyberterrorism, targeting the US economy and military infrastructure.

- The declaration of an Islamic Caliphate, which was projected between 2013 and 2016. In this phase, Al-Qaeda expected the resistance from Israel to be heavily reduced.

- The declaration of an «Islamic Army» and a «fight between believers and non-believers», also called «total confrontation».

- «Definitive Victory», projected to be completed by 2020.

According to the seven-phase strategy, the war is projected to last less than two years.

According to Charles Lister of the Middle East Institute and Katherine Zimmerman of the American Enterprise Institute, the new model of Al-Qaeda is to «socialize communities» and build a broad territorial base of operations with the support of local communities, also gaining income independent of the funding of sheiks.[156]

Name

The English name of the organization is a simplified transliteration of the Arabic noun al-qāʿidah (القاعدة), which means «the foundation» or «the base». The initial al- is the Arabic definite article «the», hence «the base».[157] In Arabic, Al-Qaeda has four syllables (/alˈqaː.ʕi.da/). However, since two of the Arabic consonants in the name are not phones found in the English language, the common naturalized English pronunciations include , and . Al-Qaeda’s name can also be transliterated as al-Qaida, al-Qa’ida, or el-Qaida.[158]

The doctrinal concept of «Al-Qaeda» was first coined by the Palestinian Islamist scholar and Jihadist leader Abdullah Azzam in an April 1988 issue of Al-Jihad magazine to describe a religiously committed vanguard of Muslims who wage armed Jihad globally to liberate oppressed Muslims from foreign invaders, establish sharia (Islamic law) across the Islamic World by overthrowing the ruling secular governments; and thus restore the past Islamic prowess. This was to be implemented by establishing an Islamic state that would nurture generations of Muslim soldiers that would perpetually attack United States and its allied governments in the Muslim World. Numerous historical models were cited by Azzam as successful examples of his call; starting from the early Muslim conquests of the 7th century to the recent anti-Soviet Afghan Jihad of 1980s.[159][160][161] According to Azzam’s world-view:

«It is about time to think about a state that would be a solid base for the distribution of the (Islamic) creed, and a fortress to host the preachers from the hell of the Jahiliyyah [the pre-Islamic period].»[161]

Bin Laden explained the origin of the term in a videotaped interview with Al Jazeera journalist Tayseer Alouni in October 2001:

The name ‘al-Qaeda’ was established a long time ago by mere chance. The late Abu Ebeida El-Banashiri established the training camps for our mujahedeen against Russia’s terrorism. We used to call the training camp al-Qaeda. The name stayed.[162]

It has been argued that two documents seized from the Sarajevo office of the Benevolence International Foundation prove the name was not simply adopted by the mujahideen movement and that a group called Al-Qaeda was established in August 1988. Both of these documents contain minutes of meetings held to establish a new military group, and contain the term «Al-Qaeda».[163]

Former British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook wrote that the word Al-Qaeda should be translated as «the database», because it originally referred to the computer file of the thousands of mujahideen militants who were recruited and trained with CIA help to defeat the Russians.[164] In April 2002, the group assumed the name Qa’idat al-Jihad (قاعدة الجهاد qāʿidat al-jihād), which means «the base of Jihad». According to Diaa Rashwan, this was «apparently as a result of the merger of the overseas branch of Egypt’s al-Jihad, which was led by Ayman al-Zawahiri, with the groups Bin Laden brought under his control after his return to Afghanistan in the mid-1990s.»[165]

Ideology

Sayyid Qutb, the Egyptian Islamic scholar and Jihadist theorist who inspired Al-Qaeda

The militant Islamist Salafist movement of Al-Qaeda developed during the Islamic revival and the rise of the Islamist movement after the Iranian Revolution (1978–1979) and the Afghan Jihad (1979-1989). Many scholars have argued that the writings of Islamic author and thinker Sayyid Qutb inspired the Al-Qaeda organization.[166] In the 1950s and 1960s, Qutb preached that because of the lack of sharia law, the Muslim world was no longer Muslim, and had reverted to the pre-Islamic ignorance known as jahiliyyah. To restore Islam, Qutb argued that a vanguard of righteous Muslims was needed in order to establish «true Islamic states», implement sharia, and rid the Muslim world of any non-Muslim influences. In Qutb’s view, the enemies of Islam included «world Jewry», which «plotted conspiracies» and opposed Islam.[167] Qutb envisioned this vanguard to march forward to wage armed Jihad against tyrannical regimes after purifying from the wider Jahili societies and organising themselves under a righteous Islamic leadership; which he viewed as the model of early Muslims in the Islamic state of Medina under the leadership of Islamic Prophet Muhammad. This idea would directly influence many Islamist figures such as Abdullah Azzam and Usama Bin Laden; and became the core rationale for the formulation of «Al-Qaeda» concept in the near future.[168] Outlining his strategy to topple the existing secular orders, Qutb argued in Milestones:

«[It is necessary that] a Muslim community to come into existence which believes that ‘there is no deity except God,’ which commits itself to obey none but God, denying all other authority, and which challenges the legality of any law which is not based on this belief.. . It should come into the battlefield with the determination that its strategy, its social organization, and the relationship between its individuals should be firmer and more powerful than the existing jahili system.»[168][169]

In the words of Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, a close college friend of bin Laden:

Islam is different from any other religion; it’s a way of life. We [Khalifa and bin Laden] were trying to understand what Islam has to say about how we eat, who we marry, how we talk. We read Sayyid Qutb. He was the one who most affected our generation.[170]

Qutb also influenced Ayman al-Zawahiri.[171] Zawahiri’s uncle and maternal family patriarch, Mafouz Azzam, was Qutb’s student, protégé, personal lawyer, and an executor of his estate. Azzam was one of the last people to see Qutb alive before his execution.[172] Zawahiri paid homage to Qutb in his work Knights under the Prophet’s Banner.[173]

Qutb argued that many Muslims were not true Muslims. Some Muslims, Qutb argued, were apostates. These alleged apostates included leaders of Muslim countries, since they failed to enforce sharia law.[174] He also alleged that the West approaches the Muslim World with a «crusading spirit»; in spite of the decline of religious values in the 20th century Europe. According to Qutb; the hostile and imperialist attitudes exhibited by Europeans and Americans towards Muslim countries, their support for Zionism, etc. reflected hatred amplified over a millennia of wars such as the Crusades and was born out of Roman materialist and utilitarian outlooks that viewed the world in monetary terms.[175]

Formation

The Afghan jihad against the pro-Soviet government further developed the Salafist Jihadist movement which inspired Al-Qaeda.[176] During this period, Al-Qaeda embraced the ideals of the South Asian militant revivalist Sayyid Ahmad Shahid (d. 1831/1246 A.H) who led a Jihad movement against British India from the frontiers of Afghanistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkwa in the early 19th century. Al-Qaeda readily adopted Sayyid Ahmad’s doctrines such as returning to the purity of early generations (Salaf as-Salih), antipathy towards Western influences and restoration of Islamic political power.[177][178] According to Pakistani journalist Hussain Haqqani,

«Sayyid Ahmed’s revival of the ideology of jihad became the prototype for subsequent Islamic militant movements in South and Central Asia and is also the main influence over the jihad network of Al Qaeda and its associated groups in the region.»[177][178]

Objectives

The long-term objective of Al-Qaeda is to unite the Muslim World under a supra-national Islamic state known as the Khilafah (Caliphate), headed by an elected Caliph descended from the Ahl al-Bayt (Prophetic family). The immediate objectives include the expulsion of American troops from the Arabian Peninsula, waging armed Jihad to topple US-allied governments in the region, etc.[179][180]

The following are the goals and some of the general policies outlined in Al-Qaeda’s Founding Charter «Al-Qaeda’s Structure and Bylaws» issued in the meetings in Peshawar in 1988.:[181][179]

«General Goals

i. To promote jihad awareness in the Islamic world

ii. To prepare and equip the cadres for the Islamic world through trainings and by participating in actual combat

iii. To support and sponsor the jihad movement as much as possible

iv. To coordinate Jihad movements around the world in an effort to create a unified international Jihad movement.General Policies

1. Complete commitment to the governing rules and controls of Shari‘a in all the beliefs and actions and according to the book [Qur’an] and Sunna as well as per the interpretation of the nation’s scholars who serve in this domain

2. Commitment to Jihad as a fight for God’s cause and as an agenda of change and to prepare for it and apply it whenever we find it possible…

4. Our position with respect to the tyrants of the world, secular and national parties and the like is not to associate with them, to discredit them and to be their constant enemy till they believe in God alone. We shall not agree with them on half-solutions and there is no way to negotiate with them or appease them

5. Our relationships with truthful Islamic jihadist movements and groups is to cooperate under the umbrella of faith and belief and we shall always attempt to at uniting and integrating with them…

6. We shall carry a relationship of love and affection with the Islamic movements who are not aligned with Jihad…

7. We shall sustain a relationship of respect and love with active scholars…

9. We shall reject the regional fanatics and will pursue Jihad in an Islamic country as needed and when possible

10. We shall care about the role of Muslim people in the Jihad and we shall attempt to recruit them…

11. We shall maintain our economic independence and will not rely on others to secure our resources.

12. Secrecy is the main ingredient of our work except for what the need deems necessary to reveal13. our policy with the Afghani Jihad is support, advise and coordination with the Islamic Establishments in Jihad arenas in a manner that conforms with our policies»

— Al-Qa`ida’s Structure and Bylaws, p.2, [182][179]

Theory of Islamic State

Al-Qaeda aims to establish an Islamic state in the Arab World, modelled after the Rashidun Caliphate, by initiating a global Jihad against the «International Jewish-Crusader Alliance» led by the United States, which it sees as the «external enemy» and against the secular governments in Muslim countries, that are described as «the apostate domestic enemy».[183] Once foreign influences and the secular ruling authorities are removed from Muslim countries through Jihad; al-Qaeda supports elections to choose the rulers of its proposed Islamic states. This is to be done through representatives of leadership councils (Shura) that would ensure the implementation of Shari’a (Islamic law). However, it opposes elections that institute parliaments which empower Muslim and non-Muslim legislators to collaborate in making laws of their own choosing.[184] In the second edition of his book Knights Under the Banner of the Prophet, Ayman Al Zawahiri writes:

«We demand… the government of the rightly guiding caliphate, which is established on the basis of the sovereignty of sharia and not on the whims of the majority. Its ummah chooses its rulers….If they deviate, the ummah brings them to account and removes them. The ummah participates in producing that government’s decisions and determining its direction. … [The caliphal state] commands the right and forbids the wrong and engages in jihad to liberate Muslim lands and to free all humanity from all oppression and ignorance.»[185]

Grievances

A recurring theme in al-Qaeda’s ideology is the perpetual grievance over the violent subjugation of Islamic dissidents by the authoritarian, secularist regimes allied to the West. Al-Qaeda denounces these post-colonial governments as a system led by Westernised elites designed to advance neo-colonialism and maintain Western hegemony over the Muslim World. The most prominent topic of grievance is over the American foreign policy in the Arab World; especially over its strong economic and military support to Israel. Other concerns of resentment include presence of NATO troops to support allied regimes; injustices committed against Muslims in Kashmir, Chechnya, Xinjiang, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq etc.[186]

Religious compatibility

Abdel Bari Atwan wrote that:

While the leadership’s own theological platform is essentially Salafi, the organization’s umbrella is sufficiently wide to encompass various schools of thought and political leanings. Al-Qaeda counts among its members and supporters people associated with Wahhabism, Shafi’ism, Malikism, and Hanafism. There are even some Al-Qaeda members whose beliefs and practices are directly at odds with Salafism, such as Yunis Khalis, one of the leaders of the Afghan mujahedin. He was a mystic who visited the tombs of saints and sought their blessings – practices inimical to bin Laden’s Wahhabi-Salafi school of thought. The only exception to this pan-Islamic policy is Shi’ism. Al-Qaeda seems implacably opposed to it, as it holds Shi’ism to be heresy. In Iraq it has openly declared war on the Badr Brigades, who have fully cooperated with the US, and now considers even Shi’i civilians to be legitimate targets for acts of violence.[187]

On the other hand, Professor Peter Mandaville states that Al-Qaeda follows a pragmatic policy in forming its local affiliates, with various cells being sub-contracted to Shia Muslim and non-Muslim members. The top-down chain of command means that each unit is answerable directly to central leadership, while they remain ignorant of their counterparts’ presence or activities. These transnational networks of autonomous supply chains, financiers, underground militias and political supporters were set up during the 1990s, when Bin Laden’s immediate aim was the expulsion of American troops from the Arabian Peninsula.[188]

Attacks on civilians

Following its 9/11 attack and in response to its condemnation by Islamic scholars, al-Qaeda provided a justification for the killing of non-combatants/civilians, entitled, «A Statement from Qaidat al-Jihad Regarding the Mandates of the Heroes and the Legality of the Operations in New York and Washington». According to a couple of critics, Quintan Wiktorowicz and John Kaltner, it provides «ample theological justification for killing civilians in almost any imaginable situation.»[189]

Among these justifications are that America is leading the west in waging a War on Islam so that attacks on America are a defense of Islam and any treaties and agreements between Muslim majority states and Western countries that would be violated by attacks are null and void. According to the tract, several conditions allow for the killing of civilians including:

- retaliation for the American war on Islam which al-Qaeda alleges has targeted «Muslim women, children and elderly»;

- when it is too difficult to distinguish between non-combatants and combatants when attacking an enemy «stronghold» (hist) and/or non-combatants remain in enemy territory, killing them is allowed;

- those who assist the enemy «in deed, word, mind» are eligible for killing, and this includes the general population in democratic countries because civilians can vote in elections that bring enemies of Islam to power;

- the necessity of killing in the war to protect Islam and Muslims;

- the prophet Muhammad, when asked whether the Muslim fighters could use the catapult against the village of Taif, replied affirmatively, even though the enemy fighters were mixed with a civilian population;

- if the women, children and other protected groups serve as human shields for the enemy;

- if the enemy has broken a treaty, killing of civilians is permitted.[189]

History

The Guardian in 2009 described five distinct phases in the development of Al-Qaeda: its beginnings in the late 1980s, a «wilderness» period in 1990–1996, its «heyday» in 1996–2001, a network period from 2001 to 2005, and a period of fragmentation from 2005 to 2009.[190]

Jihad in Afghanistan

The origins of al-Qaeda can be traced to the Soviet War in Afghanistan (December 1979 – February 1989).[23] The United States viewed the conflict in Afghanistan in terms of the Cold War, with Marxists on one side and the native Afghan mujahideen on the other. This view led to a CIA program called Operation Cyclone, which channeled funds through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency to the Afghan Mujahideen.[191] The US government provided substantial financial support to the Afghan Islamic militants. Aid to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Afghan mujahideen leader and founder of the Hezb-e Islami, amounted to more than $600 million. In addition to American aid, Hekmatyar was the recipient of Saudi aid.[192] In the early 1990s, after the US had withdrawn support, Hekmatyar «worked closely» with bin Laden.[6]

At the same time, a growing number of Arab mujahideen joined the jihad against the Afghan Marxist regime, which was facilitated by international Muslim organizations, particularly the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), also known as the «Services Bureau«. Muslim Brotherhood networks affiliated with the Egyptian Islamist Kamal al-Sananiri (d. 1981) played the major role in raising finances and Arab recruits for the Afghan Mujahidin. These networks included Mujahidin groups affiliated with Afghan commander Abd al-Rasul Sayyaf and Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, Palestinian Islamist scholar and major figure in the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood. Following the detention and death of Sananiri in an Egyptian security prison in 1981, Abdullah Azzam became the chief arbitrator between the Afghan Arabs and Afghan mujahideen.[193]

As part of providing weaponry and supplies for the cause of Afghan Jihad, Usama Bin Laden was sent to Pakistan as a Muslim Brotherhood representative to the Islamist organisation Jamaat-e-Islami. While in Peshawar, Bin Laden met Abdullah Azzam and the two of them jointly established the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK) in 1984; with objective of raising funds and recruits for Afghan Jihad across the world. MAK organized guest houses in Peshawar, near the Afghan border, and gathered supplies for the construction of paramilitary training camps to prepare foreign recruits for the Afghan war front. MAK was funded by the Saudi government as well as by individual Muslims including Saudi businessmen.[194][195][page needed] Bin Laden also became a major financier of the mujahideen, spending his own money and using his connections to influence public opinion about the war.[196] Many disgruntled members of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood like Abu Mussab al-Suri also began joining these MAK networks; following the crushing of Islamic revolt in Syria in 1982.[197]

From 1986, MAK began to set up a network of recruiting offices in the US, the hub of which was the Al Kifah Refugee Center at the Farouq Mosque on Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue. Among notable figures at the Brooklyn center were «double agent» Ali Mohamed, whom FBI special agent Jack Cloonan called «bin Laden’s first trainer»,[198] and «Blind Sheikh» Omar Abdel-Rahman, a leading recruiter of mujahideen for Afghanistan. Azzam and bin Laden began to establish camps in Afghanistan in 1987.[199]

MAK and foreign mujahideen volunteers, or «Afghan Arabs», did not play a major role in the war. While over 250,000 Afghan mujahideen fought the Soviets and the communist Afghan government, it is estimated that there were never more than two thousand foreign mujahideen on the field at any one time.[200] Nonetheless, foreign mujahideen volunteers came from 43 countries, and the total number who participated in the Afghan movement between 1982 and 1992 is reported to have been 35,000.[201] Bin Laden played a central role in organizing training camps for the foreign Muslim volunteers.[202][203]

The Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. Mohammad Najibullah’s Communist Afghan government lasted for three more years, before it was overrun by elements of the mujahideen.

Expanding operations

Toward the end of the Soviet military mission in Afghanistan, some foreign mujahideen wanted to expand their operations to include Islamist struggles in other parts of the world, such as Palestine and Kashmir. A number of overlapping and interrelated organizations were formed, to further those aspirations. One of these was the organization that would eventually be called Al-Qaeda.

Research suggests that al-Qaeda was formed on August 11, 1988, when a meeting in Afghanistan between leaders of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Abdullah Azzam, and bin Laden took place.[204] The network was founded in 1988[205] by Osama bin Laden, Abdullah Azzam,[206] and other Arab volunteers during the Soviet–Afghan War.[23] An agreement was reached to link bin Laden’s money with the expertise of the Islamic Jihad organization and take up the jihadist cause elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.[207] After fighting the «holy» war, the group aimed to expand such operations to other parts of the world, setting up bases in parts of Africa, the Arab world and elsewhere,[208] carrying out many attacks on people whom it considers kāfir.[209]

Notes indicate Al-Qaeda was a formal group by August 20, 1988. A list of requirements for membership itemized the following: listening ability, good manners, obedience, and making a pledge (Bay’at) to follow one’s superiors.[210] In his memoir, bin Laden’s former bodyguard, Nasser al-Bahri, gives the only publicly available description of the ritual of giving bay’at when he swore his allegiance to the Al-Qaeda chief.[211] According to Wright, the group’s real name was not used in public pronouncements because «its existence was still a closely held secret.»[212]

After Azzam was assassinated in 1989 and MAK broke up, significant numbers of MAK followers joined bin Laden’s new organization.[213]

In November 1989, Ali Mohamed, a former special forces sergeant stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, left military service and moved to California. He traveled to Afghanistan and Pakistan and became «deeply involved with bin Laden’s plans.»[214] In 1991, Ali Mohammed is said to have helped orchestrate bin Laden’s relocation to Sudan.[208]

Gulf War and the start of US enmity

Following the Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in February 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 had put the Kingdom and its ruling House of Saud at risk. The world’s most valuable oil fields were within striking distance of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, and Saddam’s call to Pan-Arabism could potentially rally internal dissent.

In the face of a seemingly massive Iraqi military presence, Saudi Arabia’s own forces were outnumbered. Bin Laden offered the services of his mujahideen to King Fahd to protect Saudi Arabia from the Iraqi army. The Saudi monarch refused bin Laden’s offer, opting instead to allow US and allied forces to deploy troops into Saudi territory.[215]

The deployment angered bin Laden, as he believed the presence of foreign troops in the «land of the two mosques» (Mecca and Medina) profaned sacred soil. King Fahd’s refusal of Bin Laden’s offer to train the Mujahidin; instead giving permission for American soldiers to enter Saudi territory inorder to repel Saddam Hussein’s forces would greatly anger Bin Laden. The entry of American troops into Saudi Arabia was denounced by Bin Laden as a «Crusader Attack on Islam» that defiled the sacred lands of Islam. He asserted that the Arabian Peninsula has been «occupied» by foreign invaders and excommunicated the Saudi regime due to its complicity with United States. After speaking publicly against the Saudi government for harboring American troops and rejecting their legitimacy, he was banished and forced to live in exile in Sudan. Bin Laden also vehemently denounced the elder Wahhabi scholarship; most notably Grand Mufti Abd al-Azeez Ibn Baz, accusing him of partnering with infidel forces over his verdict that permitted the entry of US troops.[216]

Sudan

From around 1992 to 1996, Al-Qaeda and bin Laden based themselves in Sudan at the invitation of Islamist theoretician Hassan al-Turabi. The move followed an Islamist coup d’état in Sudan, led by Colonel Omar al-Bashir, who professed a commitment to reordering Muslim political values. During this time, bin Laden assisted the Sudanese government, bought or set up various business enterprises, and established training camps.

A key turning point for bin Laden occurred in 1993 when Saudi Arabia gave support for the Oslo Accords, which set a path for peace between Israel and Palestinians.[217] Due to bin Laden’s continuous verbal assault on King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, Fahd sent an emissary to Sudan on March 5, 1994, demanding bin Laden’s passport. Bin Laden’s Saudi citizenship was also revoked. His family was persuaded to cut off his stipend, $7 million a year, and his Saudi assets were frozen.[218][219] His family publicly disowned him. There is controversy as to what extent bin Laden continued to garner support from members afterwards.[220]

In 1993, a young schoolgirl was killed in an unsuccessful attempt on the life of the Egyptian prime minister, Atef Sedki. Egyptian public opinion turned against Islamist bombings, and the police arrested 280 of al-Jihad’s members and executed 6.[221] In June 1995, an attempt to assassinate Egyptian president Mubarak led to the expulsion of Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), and in May 1996, of bin Laden from Sudan.[citation needed]

According to Pakistani-American businessman Mansoor Ijaz, the Sudanese government offered the Clinton Administration numerous opportunities to arrest bin Laden. Ijaz’s claims appeared in numerous op-ed pieces, including one in the Los Angeles Times[222] and one in The Washington Post co-written with former Ambassador to Sudan Timothy M. Carney.[223] Similar allegations have been made by Vanity Fair contributing editor David Rose,[224] and Richard Miniter, author of Losing bin Laden, in a November 2003 interview with World.[225]

Several sources dispute Ijaz’s claim, including the 9/11 Commission, which concluded in part:

Sudan’s minister of defense, Fatih Erwa, has claimed that Sudan offered to hand Bin Ladin over to the US. The Commission has found no credible evidence that this was so. Ambassador Carney had instructions only to push the Sudanese to expel Bin Ladin. Ambassador Carney had no legal basis to ask for more from the Sudanese since, at the time, there was no indictment out-standing.[226]

Refuge in Afghanistan

After the fall of the Afghan communist regime in 1992, Afghanistan was effectively ungoverned for four years and plagued by constant infighting between various mujahideen groups.[citation needed] This situation allowed the Taliban to organize. The Taliban also garnered support from graduates of Islamic schools, which are called madrassa. According to Ahmed Rashid, five leaders of the Taliban were graduates of Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa in the small town of Akora Khattak.[227] The town is situated near Peshawar in Pakistan, but the school is largely attended by Afghan refugees.[227] This institution reflected Salafi beliefs in its teachings, and much of its funding came from private donations from wealthy Arabs. Four of the Taliban’s leaders attended a similarly funded and influenced madrassa in Kandahar. Bin Laden’s contacts were laundering donations to these schools, and Islamic banks were used to transfer money to an «array» of charities which served as front groups for Al-Qaeda.[228]

Many of the mujahideen who later joined the Taliban fought alongside Afghan warlord Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi’s Harkat i Inqilabi group at the time of the Russian invasion. This group also enjoyed the loyalty of most Afghan Arab fighters.

The continuing lawlessness enabled the growing and well-disciplined Taliban to expand their control over territory in Afghanistan, and it came to establish an enclave which it called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In 1994, it captured the regional center of Kandahar, and after making rapid territorial gains thereafter, the Taliban captured the capital city Kabul in September 1996.

In 1996, Taliban-controlled Afghanistan provided a perfect staging ground for Al-Qaeda.[229] While not officially working together, Al-Qaeda enjoyed the Taliban’s protection and supported the regime in such a strong symbiotic relationship that many Western observers dubbed the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan as, «the world’s first terrorist-sponsored state.»[230] However, at this time, only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. In 1996, Osama Bin Laden officially issued the «Declaration of Struggle against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Mosques» which called upon Muslims all over the world to take up arms against American soldiers. In an interview with the English journalist Robert Fisk; Bin Laden criticised American imperialism and its support for Zionism as the biggest sources of tyranny in the Arab World. He vehemently denounced the US-allied Gulf monarchies; especially the Saudi government for westernising the country, removing Islamic laws and hosting American, British and French troops. Bin Laden asserted that he planned to foment an armed rebellion to overthrow the Saudi regime with the help of his Mujahidin soldiers and establish an Islamic Emirate in Arabian Peninsula that properly upholds Sharia (Islamic law).[231][232] Upon questioned whether he sought to launch a war against the Western world; Bin Laden replied:

«It is not a declaration of war — it’s a real description of the situation. This doesn’t mean declaring war against the West and Western people — but against the American regime which is against every Muslim.»[231][232]

In response to the 1998 United States embassy bombings, an Al-Qaeda base in Khost Province was attacked by the United States during Operation Infinite Reach.

While in Afghanistan, the Taliban government tasked Al-Qaeda with the training of Brigade 055, an elite element of the Taliban’s army. The Brigade mostly consisted of foreign fighters, veterans from the Soviet Invasion, and adherents to the ideology of the mujahideen. In November 2001, as Operation Enduring Freedom had toppled the Taliban government, many Brigade 055 fighters were captured or killed, and those who survived were thought to have escaped into Pakistan along with bin Laden.[233]

By the end of 2008, some sources reported that the Taliban had severed any remaining ties with Al-Qaeda,[234] however, there is reason to doubt this.[235] According to senior US military intelligence officials, there were fewer than 100 members of Al-Qaeda remaining in Afghanistan in 2009.[236]

Al Qaeda chief, Asim Omar was killed in Afghanistan’s Musa Qala district after a joint US–Afghanistan commando airstrike on September 23, Afghan’s National Directorate of Security (NDS) confirmed in October 2019.[237]

In a report released May 27, 2020, the United Nations’ Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team stated that the Taliban-Al Qaeda relations remain strong to this day and additionally, Al Qaeda itself has admitted that it operates inside Afghanistan.[238]

On July 26, 2020, a United Nations report stated that the Al Qaeda group is still active in twelve provinces in Afghanistan and its leader al-Zawahiri is still based in the country.[239] and that the UN Monitoring Team estimated that the total number of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan were «between 400 and 600».[239]

Call for global Salafi jihadism

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

In 1994, the Salafi groups waging Salafi jihadism in Bosnia entered into decline, and groups such as the Egyptian Islamic Jihad began to drift away from the Salafi cause in Europe. Al-Qaeda stepped in and assumed control of around 80% of non-state armed cells in Bosnia in late 1995. At the same time, Al-Qaeda ideologues instructed the network’s recruiters to look for Jihadi international Muslims who believed that extremist-jihad must be fought on a global level. Al-Qaeda also sought to open the «offensive phase» of the global Salafi jihad.[240] Bosnian Islamists in 2006 called for «solidarity with Islamic causes around the world», supporting the insurgents in Kashmir and Iraq as well as the groups fighting for a Palestinian state.[241]

Fatwas

In 1996, Al-Qaeda announced its jihad to expel foreign troops and interests from what they considered Islamic lands. Bin Laden issued a fatwa,[242] which amounted to a public declaration of war against the US and its allies, and began to refocus Al-Qaeda’s resources on large-scale, propagandist strikes.

On February 23, 1998, bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, a leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, along with three other Islamist leaders, co-signed and issued a fatwa calling on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies.[243] Under the banner of the World Islamic Front for Combat Against the Jews and Crusaders, they declared:

[T]he ruling to kill the Americans and their allies – civilians and military – is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque [in Jerusalem] and the holy mosque [in Mecca] from their grip, and in order for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim. This is in accordance with the words of Almighty Allah, ‘and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together [and] fight them until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail justice and faith in Allah.’[21]

Neither bin Laden nor al-Zawahiri possessed the traditional Islamic scholarly qualifications to issue a fatwa. However, they rejected the authority of the contemporary ulema (which they saw as the paid servants of jahiliyya rulers), and took it upon themselves.[244][unreliable source?]

Philippines

Al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist Ramzi Yousef operated in the Philippines in the mid-1990s and trained Abu Sayyaf soldiers.[245] The 2002 edition of the United States Department’s Patterns of Global Terrorism mention links of Abu Sayyaf to Al-Qaeda.[246] Abu Sayyaf is known for a series of kidnappings from tourists in both the Philippines and Malaysia that netted them large sums of money through ransoms. The leader of Abu Sayyaf, Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, was also a veteran fighting in the Soviet-Afghan War.[247] In 2014, Abu Sayyaf pledged allegiance to the Islamic State group.[248]

Iraq

Al-Qaeda has launched attacks against the Iraqi Shia majority in an attempt to incite sectarian violence.[249] Al-Zarqawi purportedly declared an all-out war on Shiites[250] while claiming responsibility for Shiite mosque bombings.[251] The same month, a statement claiming to be from Al-Qaeda in Iraq was rejected as a «fake».[252] In a December 2007 video, al-Zawahiri defended the Islamic State in Iraq, but distanced himself from the attacks against civilians, which he deemed to be perpetrated by «hypocrites and traitors existing among the ranks».[253]

US and Iraqi officials accused Al-Qaeda in Iraq of trying to slide Iraq into a full-scale civil war between Iraq’s Shiite population and Sunni Arabs. This was done through an orchestrated campaign of civilian massacres and a number of provocative attacks against high-profile religious targets.[254] With attacks including the 2003 Imam Ali Mosque bombing, the 2004 Day of Ashura and Karbala and Najaf bombings, the 2006 first al-Askari Mosque bombing in Samarra, the deadly single-day series of bombings in which at least 215 people were killed in Baghdad’s Shiite district of Sadr City, and the second al-Askari bombing in 2007, Al-Qaeda in Iraq provoked Shiite militias to unleash a wave of retaliatory attacks, resulting in death squad-style killings and further sectarian violence which escalated in 2006.[255] In 2008, sectarian bombings blamed on Al-Qaeda in Iraq killed at least 42 people at the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala in March, and at least 51 people at a bus stop in Baghdad in June.

In February 2014, after a prolonged dispute with Al-Qaeda in Iraq’s successor organisation, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), Al-Qaeda publicly announced it was cutting all ties with the group, reportedly for its brutality and «notorious intractability».[256]

Somalia and Yemen

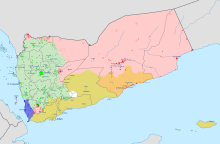

Current (December 2021) military situation in Somalia:

Current (November 2021) military situation in Yemen:

In Somalia, Al-Qaeda agents had been collaborating closely with its Somali wing, which was created from the al-Shabaab group. In February 2012, al-Shabaab officially joined Al-Qaeda, declaring loyalty in a video.[257] Somali Al-Qaeda recruited children for suicide-bomber training and recruited young people to participate in militant actions against Americans.[258]

The percentage of attacks in the First World originating from the Afghanistan–Pakistan (AfPak) border declined starting in 2007, as Al-Qaeda shifted to Somalia and Yemen.[259] While Al-Qaeda leaders were hiding in the tribal areas along the AfPak border, middle-tier leaders heightened activity in Somalia and Yemen.

In January 2009, Al-Qaeda’s division in Saudi Arabia merged with its Yemeni wing to form Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[260] Centered in Yemen, the group takes advantage of the country’s poor economy, demography and domestic security. In August 2009, the group made an assassination attempt against a member of the Saudi royal family. President Obama asked Ali Abdullah Saleh to ensure closer cooperation with the US in the struggle against the growing activity of Al-Qaeda in Yemen, and promised to send additional aid. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan drew US attention from Somalia and Yemen.[261] In December 2011, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta said the US operations against Al-Qaeda «are now concentrating on key groups in Yemen, Somalia and North Africa.»[262] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed responsibility for the 2009 bombing attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253 by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab.[263] The AQAP declared the Al-Qaeda Emirate in Yemen on March 31, 2011, after capturing the most of the Abyan Governorate.[264]

As the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen escalated in July 2015, fifty civilians had been killed and twenty million needed aid.[265] In February 2016, Al-Qaeda forces and Saudi Arabian-led coalition forces were both seen fighting Houthi rebels in the same battle.[266] In August 2018, Al Jazeera reported that «A military coalition battling Houthi rebels secured secret deals with Al-Qaeda in Yemen and recruited hundreds of the group’s fighters. … Key figures in the deal-making said the United States was aware of the arrangements and held off on drone attacks against the armed group, which was created by Osama bin Laden in 1988.»[267]

United States operations

In December 1998, the Director of the CIA Counterterrorism Center reported to President Bill Clinton that Al-Qaeda was preparing to launch attacks in the United States, and the group was training personnel to hijack aircraft.[268] On September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda attacked the United States, hijacking four airliners within the country and deliberately crashing two into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. The third plane crashed into the western side of the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia. The fourth plane was crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.[269] In total, the attackers killed 2,977 victims and injured more than 6,000 others.[270]

US officials noted that Anwar al-Awlaki had considerable reach within the US. A former FBI agent identified Awlaki as a known «senior recruiter for Al-Qaeda», and a spiritual motivator.[271] Awlaki’s sermons in the US were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers, and accused Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan. US intelligence intercepted emails from Hasan to Awlaki between December 2008 and early 2009. On his website, Awlaki has praised Hasan’s actions in the Fort Hood shooting.[272]

An unnamed official claimed there was good reason to believe Awlaki «has been involved in very serious terrorist activities since leaving the US [in 2002], including plotting attacks against America and our allies.»[273] US President Barack Obama approved the targeted killing of al-Awlaki by April 2010, making al-Awlaki the first US citizen ever placed on the CIA target list. That required the consent of the US National Security Council, and officials argued that the attack was appropriate because the individual posed an imminent danger to national security.[274][275][276] In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, who pleaded guilty to the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, told interrogators he was «inspired by» al-Awlaki, and sources said Shahzad had made contact with al-Awlaki over the Internet.[277][278][279] Representative Jane Harman called him «terrorist number one», and Investor’s Business Daily called him «the world’s most dangerous man».[280][281] In July 2010, the US Treasury Department added him to its list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists, and the UN added him to its list of individuals associated with Al-Qaeda.[282] In August 2010, al-Awlaki’s father initiated a lawsuit against the US government with the American Civil Liberties Union, challenging its order to kill al-Awlaki.[283] In October 2010, US and UK officials linked al-Awlaki to the 2010 cargo plane bomb plot.[284] In September 2011, al-Awlaki was killed in a targeted killing drone attack in Yemen.[285] On March 16, 2012, it was reported that Osama bin Laden plotted to kill US President Barack Obama.[286]

Killing of Osama bin Laden

View of Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, where he was killed on May 1, 2011

On May 1, 2011, US President Barack Obama announced that Osama bin Laden had been killed by «a small team of Americans» acting under direct orders, in a covert operation in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[287][288] The action took place 50 km (31 mi) north of Islamabad.[289] According to US officials, a team of 20–25 US Navy SEALs under the command of the Joint Special Operations Command stormed bin Laden’s compound with two helicopters. Bin Laden and those with him were killed during a firefight in which US forces experienced no casualties.[290] According to one US official the attack was carried out without the knowledge or consent of the Pakistani authorities.[291] In Pakistan some people were reported to be shocked at the unauthorized incursion by US armed forces.[292] The site is a few miles from the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul.[293] In his broadcast announcement President Obama said that US forces «took care to avoid civilian casualties».[294]

Details soon emerged that three men and a woman were killed along with bin Laden, the woman being killed when she was «used as a shield by a male combatant».[291] DNA from bin Laden’s body, compared with DNA samples on record from his dead sister,[295] confirmed bin Laden’s identity.[296] The body was recovered by the US military and was in its custody[288] until, according to one US official, his body was buried at sea according to Islamic traditions.[289][297] One US official said that «finding a country willing to accept the remains of the world’s most wanted terrorist would have been difficult.»[298] US State Department issued a «Worldwide caution» for Americans following bin Laden’s death and US diplomatic facilities everywhere were placed on high alert, a senior US official said.[299] Crowds gathered outside the White House and in New York City’s Times Square to celebrate bin Laden’s death.[300]

Syria

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (June 2020) |

Military situation in the Syrian Civil War as of April 9, 2019:

In 2003, President Bashar al-Assad revealed in an interview with a Kuwaiti newspaper that he doubted Al-Qaeda even existed. He was quoted as saying, «Is there really an entity called Al-Qaeda? Was it in Afghanistan? Does it exist now?» He went on further to remark about bin Laden, commenting «[he] cannot talk on the phone or use the Internet, but he can direct communications to the four corners of the world? This is illogical.»[302]

Following the mass protests that took place in 2011, which demanded the resignation of al-Assad, Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups and Sunni sympathizers soon began to constitute an effective fighting force against al-Assad.[303] Before the Syrian Civil War, Al-Qaeda’s presence in Syria was negligible, but its growth thereafter was rapid.[304] Groups such as the al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant have recruited many foreign Mujahideen to train and fight in what has gradually become a highly sectarian war.[305][306] Ideologically, the Syrian Civil War has served the interests of Al-Qaeda as it pits a mainly Sunni opposition against a secular government. Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalist Sunni militant groups have invested heavily in the civil conflict, at times actively backing and supporting the mainstream Syrian Opposition.[307][308]

On February 2, 2014, Al-Qaeda distanced itself from ISIS and its actions in Syria;[309] however, during 2014–15, ISIS and the Al-Qaeda-linked al-Nusra Front[310] were still able to occasionally cooperate in their fight against the Syrian government.[311][312][313] Al-Nusra (backed by Saudi Arabia and Turkey as part of the Army of Conquest during 2015–2017[314]) launched many attacks and bombings, mostly against targets affiliated with or supportive of the Syrian government.[315] From October 2015, Russian air strikes targeted positions held by al-Nusra Front, as well as other Islamist and non-Islamist rebels,[316][317][318] while the US also targeted al-Nusra with airstrikes.[318][319][320] In early 2016, a leading ISIL ideologue described Al-Qaeda as the «Jews of jihad».[321]

India

In September 2014, al-Zawahiri announced Al-Qaeda was establishing a front in India to «wage jihad against its enemies, to liberate its land, to restore its sovereignty, and to revive its Caliphate.» Al-Zawahiri nominated India as a beachhead for regional jihad taking in neighboring countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh. The motivation for the video was questioned, as it appeared the militant group was struggling to remain relevant in light of the emerging prominence of ISIS.[322] The new wing was to be known as «Qaedat al-Jihad fi’shibhi al-qarrat al-Hindiya» or al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). Leaders of several Indian Muslim organizations rejected al-Zawahiri’s pronouncement, saying they could see no good coming from it, and viewed it as a threat to Muslim youth in the country.[323]

In 2014, Zee News reported that Bruce Riedel, a former CIA analyst and National Security Council official for South Asia, had accused the Pakistani military intelligence and Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of organising and assisting Al-Qaeda to organise in India, that Pakistan ought to be warned that it will be placed on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism, and that «Zawahiri made the tape in his hideout in Pakistan, no doubt, and many Indians suspect the ISI is helping to protect him.»[324][325][326]

In September 2021, after the success of 2021 Taliban offensive, Al-Qaeda congratulated Taliban and called for liberation of Kashmir from the «clutches of the enemies of Islam».[327]

Attacks

Nairobi, Kenya: August 7, 1998

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: August 7, 1998

Aden, Yemen: October 12, 2000

World Trade Center, US: September 11, 2001

The Pentagon, US: September 11, 2001

Istanbul, Turkey: November 15 and 20, 2003

Al-Qaeda has carried out a total of six major attacks, four of them in its jihad against America. In each case the leadership planned the attack years in advance, arranging for the shipment of weapons and explosives and using its businesses to provide operatives with safehouses and false identities.[328]

1991

To prevent the former Afghan king Mohammed Zahir Shah from coming back from exile and possibly becoming head of a new government, bin Laden instructed a Portuguese convert to Islam, Paulo Jose de Almeida Santos, to assassinate Zahir Shah. On November 4, 1991, Santos entered the king’s villa in Rome posing as a journalist and tried to stab him with a dagger. A tin of cigarillos in the king’s breast pocket deflected the blade and saved Zahir Shah’s life. Santos was apprehended and jailed for 10 years in Italy.[329]

1992

On December 29, 1992, Al-Qaeda launched the 1992 Yemen hotel bombings. Two bombs were detonated in Aden, Yemen. The first target was the Movenpick Hotel and the second was the parking lot of the Goldmohur Hotel.[330]