Правители СССР

Ленин 1917–1922

Сталин 1922–1953

Маленков 1953–1955

Хрущев 1955–1964

Брежнев 1964–1982

На октябрьском пленуме ЦК в 1964 он был избран Первым секретарём ЦК КПСС. В 1966 г. 23-й съезд КПСС восстановил должность Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС, пленумом ЦК КПСС им был избран Леонид Ильич Брежнев. В 1977 г. вновь занял дожность председателя Президиума Верховного Совета СССР.

Правление Брежнева называют эпохой застоя. Подробнее »

Андропов 1982–1984

С 1973 по 1982 год — председатель Комитета государственной безопасности при Совете Министров СССР с 1967, генерал армии, Герой Социалистического Труда (1974).

В 1938–40 1-й секретарь Ярославского обкома ВЛКСМ, в 1940–1944 1-й секретарь ЦК ЛКСМ Карелии. В 1944–47 2-й секретарь Петрозаводского горкома, в 1947–51 2-й секретарь ЦК КП Карелии. В 1951–53 в аппарате ЦК КПСС. В 1953–57 посол СССР в ВНР. В 1957–1967 заведующий отделом ЦК КПСС. Член ЦК КПСС с 1961. В 1962–67 секретарь ЦК КПСС. Кандидат в члены Политбюро ЦК КПСС в 1967–73. Депутат Верховного Совета СССР 3-го, 6–10-го созывов. В 1983–1984 — Председатель Президиума Верховного Совета СССР. Подробнее »

Черненко 1984–1985

В 1941–43 секретарь Красноярского крайкома партии. В 1945–48 секретарь Пензенского обкома партии. В 1948–56 в аппарате ЦК КП Молдавии. В 1956–1960 работает в аппарате ЦК КПСС. В 1960–65 начальник Секретариата Президиума Верховного Совета СССР. С 1965 зав. отделом ЦК КПСС. Кандидат в члены ЦК КПСС в 1966–71. Член ЦК КПСС с 1971. В 1976–1984 секретарь ЦК КПСС. Депутат Верховного Совета СССР 7–11-го созывов. Подробнее »

Горбачев 1985–1991

С 1955 по 1966 занимается комсомольской деятельностью в Ставрополе. В 1966–1970 г.г. — Первый секретарь Ставропольского горкома, в 1970–78 — 1-й секретарь Ставропольского крайкома КПСС. В 1978 избирается секретарем ЦК КПСС. В 1979 году — кандидат в члены Политбюро, с 1980 по 1991 — член Политбюро ЦК КПСС. В марте 1990 г. на Третьем съезде народных депутатов СССР был избран Президентом СССР. 25 декабря 1991 г. после Беловежского Соглашения ушёл в отставку. Подробнее »

См. также:

- Биографии выдающихся деятелей

- Номинальные главы СССР

- Главы правительства СССР

Похожие статьи:

Просмотров 101к. Обновлено 21.09.2022

Содержание

- Высшая должность в государстве

- 1917. Ленин Владимир Ильич

- 1924. Сталин Иосиф Виссарионович

- 1953. Маленков Георгий Максимилианович

- 1953. Хрущёв Никита Сергеевич

- 1964. Брежнев Леонид Ильич

- 1982. Андропов Юрий Владимирович

- 1984. Черненко Константин Устинович

- 1985. Горбачёв Михаил Сергеевич

Высшая должность в государстве

За время существования Советского Союза было всего восемь руководителей СССР, являющихся одними из самых известных личностей не только в Советском государстве, но и за его пределами, это: Владимир Ленин, Иосиф Сталин, Георгий Маленков, Никита Хрущёв, Леонид Брежнев, Юрий Андропов, Константин Черненко, Михаил Горбачёв. После смерти создателя СССР Владимира Ленина, высшая должность в Коммунистической Партии стала фактически высшей руководящей государственной должностью в СССР. Формально высшим органом власти в СССР, начиная с 1938 года, был Верховный Совет, однако в действительности ни Президиум, ни его Председатель не имели той власти, какая была у главы коммунистической партии.

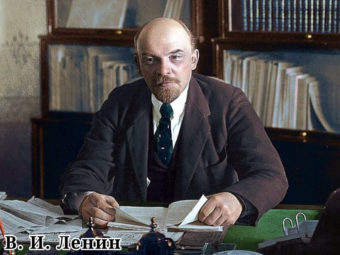

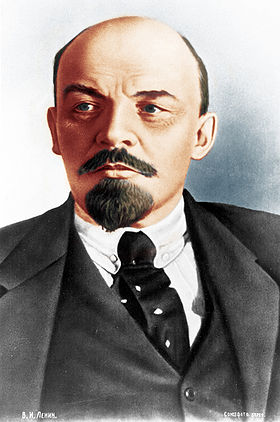

1917. Ленин Владимир Ильич

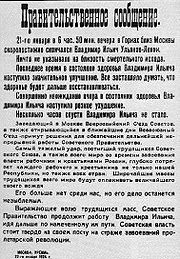

22 апреля 1870 — 21 января 1924

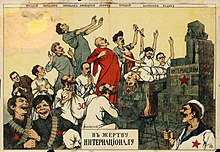

Ленин Владимир Ильич (22 апреля 1870 – 21 января 1924) – руководитель РСФСР и СССР в должности Председателя Совета народных комиссаров РСФСР и СССР. Российский революционер, создатель РСДРП(б), организатор и руководитель Октябрьской революции 1917 года, основатель и первый руководитель СССР. Именно Ленин провозгласил курс на свержение буржуазии и переход власти к Советам. По его инициативе в 1918 году был заключён Брестский мир с Германией. Ленин был инициатором и одним из главных организаторов политики красного террора. Ленин запустил процесс реорганизации промышленности и социальной сферы России, способствовал развитию науки.

1924. Сталин Иосиф Виссарионович

18 декабря 1878 – 5 марта 1953

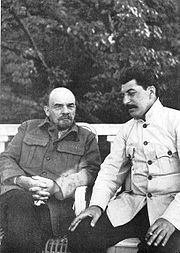

Сталин Иосиф Виссарионович (18 декабря 1878 – 5 марта 1953) – руководитель СССР в 1924-1953 гг. в должности Генерального секретаря ЦК ВКП(б) (КПСС). Российский революционер, участник Гражданской войны, председатель Государственного комитета обороны в 1941-1945 гг. В конце 20-х годов взял курс на форсированную индустриализацию, коллективизацию и построение плановой экономики, что обеспечило рост национального дохода. В период правления Сталина имели место массовые политические репрессии, некоторые народы подверглись тотальной депортации. Правление Сталина ознаменовано победой в Великой Отечественной войне. В 1949 году СССР стал ядерной сверхдержавой.

1953. Маленков Георгий Максимилианович

8 января 1902 — 14 января 1988

Маленков Георгий Максимилианович (8 января 1902 – 14 января 1988) – фактический руководитель СССР в 1953-1955 гг. в должности Председателя Совета Министров СССР (возглавив КПСС 7 сентября 1953 года реальным руководителем СССР стал Н. С. Хрущёв). Будучи соратником И. В. Сталина, Маленков принимал активное участие в репрессиях 30-х годов, имел прямое отношение к следствию по “Ленинградскому” и подобным делам, однако первым заговорил о культе личности Сталина. Способствовал устранению Берии и Ежова. Выступал за борьбу с привилегиями и бюрократизмом партийного и государственного аппарата. В 1957 году предпринял попытку смещения Хрущёва, в 1961 году исключён из КПСС.

1953. Хрущёв Никита Сергеевич

15 апреля 1894 — 11 сентября 1971

Хрущёв Никита Сергеевич (15 апреля 1894 — 11 сентября 1971) — руководитель СССР в 1953-1964 гг. в должности Первого секретаря ЦК КПСС. Участник Гражданской войны, участник Великой Отечественной войны, Первый секретарь ЦК КП(б) Украины в 1938-1947 гг. Инициатор ареста Берии, на XX съезде осудил культ личности Сталина. С именем Н.С. Хрущёва связывают период “оттепели” во внутренней и внешней политике. В период его руководства было подавлено Венгерское восстание (1956), разразился Карибский кризис (1962), СССР первым отправил человека в космос, началось массовое жилищное строительство. Отстранён от должности Первого секретаря ЦК КПСС 14 октября 1964 года на Пленуме ЦК.

1964. Брежнев Леонид Ильич

19 декабря 1906 — 10 ноября 1982

Брежнев Леонид Ильич (19 декабря 1906 — 10 ноября 1982) — руководитель СССР в 1964-1982 гг. в должности Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС. Участник Великой Отечественной войны и Парада Победы. Период руководства Брежнева в СССР признан самым стабильным в социальном плане. Советский народ получал бесплатное образование и медицинское обслуживание, обеспечивался жильём. Однако зависимость от экспорта ресурсов, военные расходы и коррупция привели к застою в экономике. При Брежневе решительно подавлялось инакомыслие, были введены войска ОВД в Чехословакию (1968), началась Афганская война (1979). Во внешней политике Брежнев стремился к разрядке международной напряжённости.

1982. Андропов Юрий Владимирович

15 июня 1914 — 9 февраля 1984

Андропов Юрий Владимирович (15 июня 1914 — 9 февраля 1984) — руководитель СССР в 1982-1984 гг. в должности Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС. Участник Великой Отечественной войны, председатель КГБ СССР в 1967-1982 гг. Под руководством Андропова КГБ существенно расширил свой контроль над обществом, усилились репрессии в отношении диссидентов. Во главе СССР Андропов начал борьбу за повышение экономической эффективности социалистической системы: принял жёсткие меры по укреплению трудовой дисциплины, провёл чистку партийного и государственного аппарата. В 1983 году началась подготовка «долгосрочной программы кардинальной перестройки управления народным хозяйством».

1984. Черненко Константин Устинович

24 сентября 1911 — 10 марта 1985

Черненко Константин Устинович (24 сентября 1911 — 10 марта 1985) — руководитель СССР в 1984-1985 гг. в должности Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС. Черненко заявлял о необходимости модернизации экономики, однако уделял больше внимания организационно-пропагандистским мероприятиям, чем экономической ситуации в стране. При Черненко партийно-бюрократический аппарат был раздут до невероятных размеров. Экономика страны замедлилась, было закуплено колоссальное количество продовольствия и промышленных товаров. Наметилось потепление отношений с КНР, однако отношения с США оставались напряжёнными, в 1984 году СССР бойкотировал Олимпийские игры в Лос-Анджелесе.

1985. Горбачёв Михаил Сергеевич

2 марта 1931 — 30 августа 2022

Горбачёв Михаил Сергеевич (2 марта 1931 — 30 августа 2022) — руководитель СССР в 1985-1991 гг. в должности Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС и президента СССР (1990-1991). Первый и последний президент СССР. В январе 1987 г. на пленуме ЦК КПСС дал старт политике «перестройки», которая в дальнейшем привела к рыночной экономике, свободным выборам, утрате монополии КПСС на власть и распаду СССР. Многочисленные реформы, призванные изменить советскую экономику в направлении рыночной модели хозяйствования, привели к глубокому экономическому кризису. Политика Горбачёва способствовала прекращению холодной войны, снятию «железного занавеса» и ослаблению ядерной угрозы. Были выведены советские войска из Афганистана. Лауреат нобелевской премия мира 1990 г.

https://ria.ru/20170414/1491767713.html

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина) — РИА Новости, 03.03.2020

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Советский государственный и политический деятель, теоретик марксизма, основатель Коммунистической партии и Советского социалистического государства в России… РИА Новости, 14.04.2017

2017-04-14T10:30

2017-04-14T10:30

2020-03-03T03:49

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/147870/22/1478702220_0:0:1742:980_1920x0_80_0_0_14ff7d913a53cb5196df4abbfc68367e.jpg

россия

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2017

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

Новости

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/147870/22/1478702220_0:0:1742:1308_1920x0_80_0_0_cb774298bf79e5f60b05e4d3fd3b02c2.jpg

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

картотека — великая русская революция, владимир ленин (владимир ульянов), россия

Картотека — Великая русская революция, Владимир Ленин (Владимир Ульянов), Россия

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Советский государственный и политический деятель, теоретик марксизма, основатель Коммунистической партии и Советского социалистического государства в России Владимир Ильич Ульянов (Ленин) родился 22 апреля (10 апреля по старому стилю) 1870 года в Симбирске (ныне Ульяновск) в семье инспектора народных училищ, ставшего потомственным дворянином.

Его старший брат Александр — революционер-народоволец, в мае 1887 года был казнен за подготовку покушения на царя.

В том же году Владимир Ульянов окончил Симбирскую гимназию с золотой медалью, был принят в Казанский университет, но через три месяца после поступления был исключен за участие в студенческих беспорядках. В 1891 году Ульянов экстерном окончил юридический факультет Петербургского университета, после чего работал в Самаре в должности помощника присяжного поверенного.

В августе 1893 года он переехал в Санкт-Петербург, где вступил в марксистский кружок студентов Технологического института. В апреле 1895 года Владимир Ульянов выехал за границу и познакомился с группой «Освобождение труда», созданной в Женеве русскими эмигрантами во главе с Георгием Плехановым. Осенью того же года по его инициативе и под его руководством марксистские кружки Петербурга объединились в единый «Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса». В декабре 1895 года Ульянов был арестован полицией. Провел более года в тюрьме, затем выслан на три года в село Шушенское Минусинского уезда Красноярского края под гласный надзор полиции.

Участниками «Союза» в 1898 году в Минске был проведен первый съезд Российской социал-демократической рабочей партии (РСДРП).

Находясь в ссылке, Владимир Ульянов продолжал теоретическую и организационную революционную деятельность. В 1897 году издал работу «Развитие капитализма в России», где пытался оспорить взгляды народников на социально-экономические отношения в стране и доказать, что в России назревает буржуазная революция. Познакомился с работами ведущего теоретика немецкой социал-демократии Карла Каутского, у которого заимствовал идею организации русского марксистского движения в виде централизованной партии «нового типа».

После окончания срока ссылки в январе 1900 года выехал за границу (последующие пять лет жил в Мюнхене, Лондоне и Женеве). Там, вместе с Георгием Плехановым, его соратниками Верой Засулич и Павлом Аксельродом, а также своим другом Юлием Мартовым, Владимир Ульянов начал издавать социал-демократическую газету «Искра». С 1901 года он стал использовать псевдоним «Ленин» и с тех пор был известен в партии под этим именем.

В 1903 году на II съезде российских социал-демократов в результате раскола на меньшевиков и большевиков Ленин возглавил «большинство», создав затем большевистскую партию.

С 1905 года по 1907 год Ленин нелегально жил в Петербурге, осуществляя руководство левыми силами. С 1907 года по 1917 год находился в эмиграции, где отстаивал свои политические взгляды во II Интернационале.

В начале Первой мировой войны, находясь на территории Австро-Венгрии, Ленин был арестован по подозрению в шпионаже в пользу Российского правительства, но благодаря участию австрийских социал-демократов был освобожден. После освобождения уехал в Швейцарию, где выдвинул лозунг о превращении империалистической войны в войну гражданскую.

Весной 1917 года Ленин вернулся в Россию. 17 апреля (4 апреля по старому стилю) 1917 года, на следующий день после прибытия в Петроград, он выступил с так называемыми «Апрельскими тезисами», где изложил программу перехода от буржуазно-демократической революции к социалистической, а также начал подготовку вооруженного восстания и свержения Временного правительства.

С апреля 1917 года Ленин становится одним из главных организаторов и руководителей Октябрьского вооруженного восстания и установления власти Советов.

В начале октября 1917 года он нелегально переехал из Выборга в Петроград. 23 октября (10 октября по старому стилю) на заседании Центрального Комитета РСДРП(б) по его предложению была принята резолюция о вооруженном восстании. 6 ноября (24 октября по старому стилю) в письме к ЦК Ленин потребовал немедленного перехода в наступление, ареста Временного правительства и захвата власти. Для непосредственного руководства вооруженным восстанием вечером он нелегально прибыл в Смольный. На следующий день, 7 ноября (25 октября по старому стилю) 1917 года в Петрограде произошло восстание и захват государственной власти большевиками. На открывшемся вечером заседании второго Всероссийского съезда Советов было провозглашено советское правительство — Совет Народных Комиссаров (СНК), председателем которого стал Владимир Ленин. Съездом были приняты первые декреты, подготовленные Лениным: о прекращении войны и о передаче частной земли в пользование трудящихся.

По инициативе Ленина в 1918 году был заключен Брестский мир с Германией.

После переноса столицы из Петрограда в Москву с марта 1918 года Ленин жил и работал в Москве. Его личная квартира и рабочий кабинет размещались в Кремле, на третьем этаже бывшего здания Сената. Ленин избирался депутатом Моссовета.

Весной 1918 года правительство Ленина начало борьбу против оппозиции закрытием анархистских и социалистических рабочих организаций, в июле 1918 года Ленин руководил подавлением вооруженного выступления левых эсеров. Противостояние ужесточилось в период Гражданской войны, эсеры, левые эсеры и анархисты, в свою очередь, наносили удары по деятелям большевистского режима; 30 августа 1918 года было совершено покушение на Ленина.

Во время Гражданской войны Ленин стал инициатором и идеологом политики «военного коммунизма». Он одобрил создание Всероссийской чрезвычайной комиссии по борьбе с контрреволюцией и саботажем (ВЧК), широко и бесконтрольно применявшей методы насилия и репрессий.

С окончанием Гражданской войны и прекращением военной интервенции в 1922 году начался процесс восстановления народного хозяйства страны. С этой целью по настоянию Ленина был отменен «военный коммунизм», продовольственная разверстка была заменена продовольственным налогом. Ленин ввел так называемую новую экономическую политику (НЭП), разрешившую частную свободную торговлю. В то же время он настаивал на развитии предприятий государственного типа, на электрификации, на развитии кооперации.

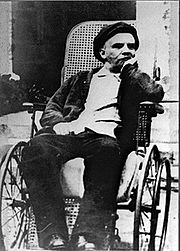

В мае и декабре 1922 года Ленин перенес два инсульта, однако продолжал диктовать заметки и статьи, посвященные партийным и государственным делам. Третий инсульт, последовавший в марте 1923 года, сделал его практически недееспособным.

21 января 1924 года Владимир Ленин скончался в подмосковном поселке Горки. 23 января гроб с его телом был перевезен в Москву и установлен в Колонном зале Дома Союзов. Официальное прощание проходило в течение пяти дней.

27 января 1924 года гроб с забальзамированным телом Ленина был помещен в специально построенном на Красной площади Мавзолее по проекту архитектора Алексея Щусева.

В годы советской власти на различных зданиях, связанных с деятельностью Ленина, были установлены мемориальные доски, в городах установлены памятники вождю. Были учреждены: орден Ленина (1930), премия имени Ленина (1925), Ленинские премии за достижения в области науки, техники, литературы, искусства, архитектуры (1957). В 1924-1991 годах в Москве работал Центральный музей Ленина. Именем Ленина был назван ряд предприятий, учреждений и учебных заведений.

В 1923 году ЦК РКП(б) создал Институт В И. Ленина, а в 1932 году в результате его объединения с Институтом Маркса и Энгельса был образован единый Институт Маркса — Энгельса — Ленина при ЦК ВКП(б) (позднее он стал называться Институтом марксизма-ленинизма при ЦК КПСС). В Центральном партийном архиве этого института (ныне — Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории) хранится более 30 тысяч документов, автором которых является Владимир Ленин.

Ленин был женат на Надежде Крупской, которую знал еще по петербургскому революционному подполью. Они обвенчались 22 июля 1898 года во время ссылки Владимира Ульянова в село Шушенское.

Материал подготовлен на основе информации РИА Новости и открытых источников

|

Vladimir Lenin |

|

|---|---|

|

Владимир Ленин |

|

Lenin in 1920 |

|

| Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 6 July 1923 – 21 January 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Rykov |

| Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 21 January 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Rykov |

| Member of the Russian Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 November 1917 – 20 January 1918[a] Serving with Pavel Dybenko |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Constituency | Baltic Fleet |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov 22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1870 |

| Died | 21 January 1924 (aged 53) Gorki, Moscow Governorate, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Lenin’s Mausoleum, Moscow |

| Political party |

|

| Other political affiliations |

League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class (1895–1898) |

| Spouse |

Nadezhda Krupskaya (m. 1898) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

4 siblings

|

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University |

| Signature | |

|

Recorded 1919 |

|

|

Central institution membership

Military offices held

Leader of the Soviet Union

|

|

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov[b] (22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,[c] was a Russian lawyer, revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1924 and of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1924. Under his administration, Russia, and later the Soviet Union, became a one-party socialist state governed by the Communist Party. Ideologically a Marxist, his development of the ideology is known as Leninism.

Born to an upper-middle-class family in Simbirsk, Lenin embraced revolutionary socialist politics following his brother’s 1887 execution. Expelled from Kazan Imperial University for participating in protests against the Russian Empire’s Tsarist government, he devoted the following years to a law degree. He moved to Saint Petersburg in 1893 and became a senior Marxist activist. In 1897, he was arrested for sedition and exiled to Shushenskoye in Siberia for three years, where he married Nadezhda Krupskaya. After his exile, he moved to Western Europe, where he became a prominent theorist in the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). In 1903, he took a key role in the RSDLP ideological split, leading the Bolshevik faction against Julius Martov’s Mensheviks. Following Russia’s failed Revolution of 1905, he campaigned for the First World War to be transformed into a Europe-wide proletarian revolution, which, as a Marxist, he believed would cause the overthrow of capitalism and its replacement with socialism. After the 1917 February Revolution ousted the Tsar and established a Provisional Government, he returned to Russia to play a leading role in the October Revolution in which the Bolsheviks overthrew the new regime.

Lenin’s Bolshevik government initially shared power with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, elected soviets, and a multi-party Constituent Assembly, although by 1918 it had centralised power in the new Communist Party. Lenin’s administration redistributed land among the peasantry and nationalised banks and large-scale industry. It withdrew from the First World War by signing a treaty conceding territory to the Central Powers, and promoted world revolution through the Communist International. Opponents were suppressed in the Red Terror, a violent campaign administered by the state security services; tens of thousands were killed or interned in concentration camps. His administration defeated right and left-wing anti-Bolshevik armies in the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1922 and oversaw the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1921. Responding to wartime devastation, famine, and popular uprisings, in 1921 Lenin encouraged economic growth through the New Economic Policy. Several non-Russian nations had secured independence from the Russian Republic after 1917, but five were forcibly re-united into the new Soviet Union in 1922, while others repelled Soviet invasions. In 1922, Lenin formed a bloc alliance with Leon Trosky to counter the bureaucratisation of the party and the growing influence of Stalin [2]. His health failing, Lenin died in Gorki, with Joseph Stalin succeeding him as the pre-eminent figure in the Soviet government.

Widely considered one of the most significant and influential figures of the 20th century, Lenin was the posthumous subject of a pervasive personality cult within the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. He became an ideological figurehead behind Marxism–Leninism and a prominent influence over the international communist movement. A controversial and highly divisive historical figure, Lenin is viewed by his supporters as a champion of socialism and the working class with progressive policies that institutionalised universal literacy, universal healthcare and equal rights for women.[3][4] Meanwhile, Lenin’s critics accuse him of establishing a totalitarian dictatorship which oversaw mass killings and political repression.

Early life

Childhood: 1870–1887

Lenin’s childhood home in Simbirsk (pictured in 2009)

Going back to his great-grandparents, Russian, German, Swedish, Jewish and reportedly some distant Kalmyk ancestry has been discovered.[5] His father Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov was from a family of former serfs; Ilya’s father’s ethnicity remains unclear,[d] while Ilya’s mother, Anna Alexeyevna Smirnova, was half-Kalmyk and half-Russian.[7] Despite a lower-class background, Ilya had risen to middle-class status, studying physics and mathematics at Kazan University before teaching at the Penza Institute for the Nobility.[8] Ilya married Maria Alexandrovna Blank in mid-1863.[9] Well educated, she was the daughter of a wealthy German–Swedish Lutheran mother, and a Russian Jewish father who had converted to Christianity and worked as a physician.[10] According to historian Petrovsky-Shtern, it is likely that Lenin was unaware of his mother’s half-Jewish ancestry, which was only discovered by his sister Anna after his death.[11] According to another version, Maria’s father came from a family of German colonists invited to Russia by Catherine the Great.[12]

Soon after their wedding, Ilya obtained a job in Nizhny Novgorod, rising to become Director of Primary Schools in the Simbirsk district six years later. Five years after that, he was promoted to Director of Public Schools for the province, overseeing the foundation of over 450 schools as a part of the government’s plans for modernisation. In January 1882, his dedication to education earned him the Order of Saint Vladimir, which bestowed on him the status of hereditary nobleman.[13]

An image of Lenin (left) at the age of three with his sister, Olga

Lenin was born in Streletskaya Ulitsa, Simbirsk, now Ulyanovsk, on 22 April 1870, and baptised six days later;[14] as a child, he was known as Volodya, a diminutive of Vladimir.[15] He was the third of eight children, having two older siblings, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1866). They were followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874), and Maria (born 1878). Two later siblings died in infancy.[16] Ilya was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church and baptised his children into it, although Maria, a Lutheran by upbringing, was largely indifferent to Christianity, a view that influenced her children.[17]

Both of his parents were monarchists and liberal conservatives, being committed to the emancipation reform of 1861 introduced by the reformist Tsar Alexander II; they avoided political radicals and there is no evidence that the police ever put them under surveillance for subversive thought.[18] Every summer they holidayed at a rural manor in Kokushkino.[19] Among his siblings, Lenin was closest to his sister Olga, whom he often bossed around; he had an extremely competitive nature and could be destructive, but usually admitted his misbehaviour.[20] A keen sportsman, he spent much of his free time outdoors or playing chess, and excelled at school, the disciplinarian and conservative Simbirsk Classical Gymnasium.[21]

In January 1886, when Lenin was 15, his father died of a brain haemorrhage.[22] Subsequently, his behaviour became erratic and confrontational and he renounced his belief in God.[23] At the time, Lenin’s elder brother Alexander, whom he affectionately knew as Sasha, was studying at Saint Petersburg University. Involved in political agitation against the absolute monarchy of the reactionary Tsar Alexander III, Alexander studied the writings of banned leftists and organised anti-government protests. He joined a revolutionary cell bent on assassinating the Tsar and was selected to construct a bomb. Before the attack could take place, the conspirators were arrested and tried, and Alexander was executed by hanging in May.[24] Despite the emotional trauma of his father’s and brother’s deaths, Lenin continued studying, graduated from school at the top of his class with a gold medal for exceptional performance, and decided to study law at Kazan University.[25]

University and political radicalisation: 1887–1893

Upon entering Kazan University in August 1887, Lenin moved into a nearby flat.[26] There, he joined a zemlyachestvo, a form of university society that represented the men of a particular region.[27] This group elected him as its representative to the university’s zemlyachestvo council, and he took part in a December demonstration against government restrictions that banned student societies. The police arrested Lenin and accused him of being a ringleader in the demonstration; he was expelled from the university, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs exiled him to his family’s Kokushkino estate.[28] There, he read voraciously, becoming enamoured with Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s 1863 pro-revolutionary novel What Is to Be Done?[29]

Lenin’s mother was concerned by her son’s radicalisation, and was instrumental in convincing the Interior Ministry to allow him to return to the city of Kazan, but not the university.[30] On his return, he joined Nikolai Fedoseev’s revolutionary circle, through which he discovered Karl Marx’s 1867 book Capital. This sparked his interest in Marxism, a socio-political theory that argued that society developed in stages, that this development resulted from class struggle, and that capitalist society would ultimately give way to socialist society and then communist society.[31] Wary of his political views, Lenin’s mother bought a country estate in Alakaevka village, Samara Oblast, in the hope that her son would turn his attention to agriculture. He had little interest in farm management, and his mother soon sold the land, keeping the house as a summer home.[32]

Lenin was influenced by the works of Karl Marx.

In September 1889, the Ulyanov family moved to the city of Samara, where Lenin joined Alexei Sklyarenko’s socialist discussion circle.[33] There, Lenin fully embraced Marxism and produced a Russian language translation of Marx and Friedrich Engels’s 1848 political pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto.[34] He began to read the works of the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, agreeing with Plekhanov’s argument that Russia was moving from feudalism to capitalism and so socialism would be implemented by the proletariat, or urban working class, rather than the peasantry.[35] This Marxist perspective contrasted with the view of the agrarian-socialist Narodnik movement, which held that the peasantry could establish socialism in Russia by forming peasant communes, thereby bypassing capitalism. This Narodnik view developed in the 1860s with the People’s Freedom Party and was then dominant within the Russian revolutionary movement.[36] Lenin rejected the premise of the agrarian-socialist argument, but was influenced by agrarian-socialists like Pyotr Tkachev and Sergei Nechaev, and befriended several Narodniks.[37]

In May 1890, Maria, who retained societal influence as the widow of a nobleman, persuaded the authorities to allow Lenin to take his exams externally at the University of St Petersburg, where he obtained the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours. The graduation celebrations were marred when his sister Olga died of typhoid.[38] Lenin remained in Samara for several years, working first as a legal assistant for a regional court and then for a local lawyer.[39] He devoted much time to radical politics, remaining active in Sklyarenko’s group and formulating ideas about how Marxism applied to Russia. Inspired by Plekhanov’s work, Lenin collected data on Russian society, using it to support a Marxist interpretation of societal development and counter the claims of the Narodniks.[40] He wrote a paper on peasant economics; it was rejected by the liberal journal Russian Thought.[41]

Revolutionary activity

Early activism and imprisonment: 1893–1900

In late 1893, Lenin moved to Saint Petersburg.[42] There, he worked as a barrister’s assistant and rose to a senior position in a Marxist revolutionary cell that called itself the Social-Democrats after the Marxist Social Democratic Party of Germany.[43] Publicly championing Marxism within the socialist movement, he encouraged the founding of revolutionary cells in Russia’s industrial centres.[44] By late 1894, he was leading a Marxist workers’ circle, and meticulously covered his tracks, knowing that police spies tried to infiltrate the movement.[45] He began a romantic relationship with Nadezhda «Nadya» Krupskaya, a Marxist schoolteacher.[46] He also authored the political tract What the «Friends of the People» Are and How They Fight the Social-Democrats criticising the Narodnik agrarian-socialists, based largely on his experiences in Samara; around 200 copies were illegally printed in 1894.[47]

Lenin hoped to cement connections between his Social-Democrats and Emancipation of Labour, a group of Russian Marxist émigrés based in Switzerland; he visited the country to meet group members Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod.[48] He proceeded to Paris to meet Marx’s son-in-law Paul Lafargue and to research the Paris Commune of 1871, which he considered an early prototype for a proletarian government.[49] Financed by his mother, he stayed in a Swiss health spa before travelling to Berlin, where he studied for six weeks at the Staatsbibliothek and met the Marxist activist Wilhelm Liebknecht.[50] Returning to Russia with a stash of illegal revolutionary publications, he travelled to various cities distributing literature to striking workers.[51] While involved in producing a news sheet, Rabochee delo (Workers’ Cause), he was among 40 activists arrested in St. Petersburg and charged with sedition.[52]

Refused legal representation or bail, Lenin denied all charges against him but remained imprisoned for a year before sentencing.[53] He spent this time theorising and writing. In this work he noted that the rise of industrial capitalism in Russia had caused large numbers of peasants to move to the cities, where they formed a proletariat. From his Marxist perspective, Lenin argued that this Russian proletariat would develop class consciousness, which would in turn lead them to violently overthrow tsarism, the aristocracy, and the bourgeoisie and to establish a proletariat state that would move toward socialism.[54]

In February 1897, Lenin was sentenced without trial to three years’ exile in eastern Siberia. He was granted a few days in Saint Petersburg to put his affairs in order and used this time to meet with the Social-Democrats, who had renamed themselves the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.[55] His journey to eastern Siberia took 11 weeks, for much of which he was accompanied by his mother and sisters. Deemed only a minor threat to the government, he was exiled to a peasant’s hut in Shushenskoye, Minusinsky District, where he was kept under police surveillance; he was nevertheless able to correspond with other revolutionaries, many of whom visited him, and permitted to go on trips to swim in the Yenisei River and to hunt duck and snipe.[56]

In May 1898, Nadya joined him in exile, having been arrested in August 1896 for organising a strike. She was initially posted to Ufa, but persuaded the authorities to move her to Shushenskoye, claiming that she and Lenin were engaged; they married in a church on 10 July 1898.[57] Settling into a family life with Nadya’s mother Elizaveta Vasilyevna, in Shushenskoye the couple translated English socialist literature into Russian.[58] Keen to keep up with developments in German Marxism, where there had been an ideological split, with revisionists like Eduard Bernstein advocating a peaceful, electoral path to socialism, Lenin remained devoted to violent revolution, attacking revisionist arguments in A Protest by Russian Social-Democrats.[59] He also finished The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899), his longest book to date, which criticised the agrarian-socialists and promoted a Marxist analysis of Russian economic development. Published under the pseudonym of Vladimir Ilin, upon publication it received predominantly poor reviews.[60]

Munich, London, and Geneva: 1900–1905

Lenin in 1916, while in Switzerland

After his exile, Lenin settled in Pskov in early 1900.[61] There, he began raising funds for a newspaper, Iskra (Spark), a new organ of the Russian Marxist party, now calling itself the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).[62] In July 1900, Lenin left Russia for Western Europe; in Switzerland he met other Russian Marxists, and at a Corsier conference they agreed to launch the paper from Munich, where Lenin relocated in September.[63] Containing contributions from prominent European Marxists, Iskra was smuggled into Russia,[64] becoming the country’s most successful underground publication for 50 years.[65] He first adopted the pseudonym Lenin in December 1901, possibly based on the Siberian River Lena;[66] he often used the fuller pseudonym of N. Lenin, and while the N did not stand for anything, a popular misconception later arose that it represented Nikolai.[67] Under this pseudonym, he published the political pamphlet What Is to Be Done? in 1902; his most influential publication to date, it dealt with Lenin’s thoughts on the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat to revolution.[68]

His wife Nadya joined Lenin in Munich and became his personal secretary.[69] They continued their political agitation, as Lenin wrote for Iskra and drafted the RSDLP programme, attacking ideological dissenters and external critics, particularly the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR),[70] a Narodnik agrarian-socialist group founded in 1901.[71] Despite remaining a Marxist, he accepted the Narodnik view on the revolutionary power of the Russian peasantry, accordingly penning the 1903 pamphlet To the Village Poor.[72] To evade Bavarian police, Lenin moved to London with Iskra in April 1902.[73] He became friends with fellow Russian-Ukrainian Marxist Leon Trotsky.[74] Lenin fell ill with erysipelas and was unable to take such a leading role on the Iskra editorial board; in his absence, the board moved its base of operations to Geneva.[75]

The second RSDLP Congress was held in London in July 1903.[76] At the conference, a schism emerged between Lenin’s supporters and those of Julius Martov. Martov argued that party members should be able to express themselves independently of the party leadership; Lenin disagreed, emphasising the need for a strong leadership with complete control over the party.[77] Lenin’s supporters were in the majority, and he termed them the «majoritarians» (bol’sheviki in Russian; Bolsheviks); in response, Martov termed his followers the «minoritarians» (men’sheviki in Russian; Mensheviks).[78] Arguments between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks continued after the conference; the Bolsheviks accused their rivals of being opportunists and reformists who lacked discipline, while the Mensheviks accused Lenin of being a despot and autocrat.[79] Enraged at the Mensheviks, Lenin resigned from the Iskra editorial board and in May 1904 published the anti-Menshevik tract One Step Forward, Two Steps Back.[80] The stress made Lenin ill, and to recuperate he went on a hiking holiday in rural Switzerland.[81] The Bolshevik faction grew in strength; by spring 1905, the whole RSDLP Central Committee was Bolshevik,[82] and in December they founded the newspaper Vpered (Forward).[83]

Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath: 1905–1914

In January 1905, the Bloody Sunday massacre of protesters in St. Petersburg sparked a spate of civil unrest in the Russian Empire known as the Revolution of 1905.[84] Lenin urged Bolsheviks to take a greater role in the events, encouraging violent insurrection.[85] In doing so, he adopted SR slogans regarding «armed insurrection», «mass terror», and «the expropriation of gentry land», resulting in Menshevik accusations that he had deviated from orthodox Marxism.[86] In turn, he insisted that the Bolsheviks split completely with the Mensheviks; many Bolsheviks refused, and both groups attended the Third RSDLP Congress, held in London in April 1905 at the Brotherhood Church.[87] Lenin presented many of his ideas in the pamphlet Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, published in August 1905. Here, he predicted that Russia’s liberal bourgeoisie would be sated by a transition to constitutional monarchy and thus betray the revolution; instead he argued that the proletariat would have to build an alliance with the peasantry to overthrow the Tsarist regime and establish the «provisional revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.»[88]

The uprising has begun. Force against Force. Street fighting is raging, barricades are being thrown up, rifles are cracking, guns are booming. Rivers of blood are flowing, the civil war for freedom is blazing up. Moscow and the South, the Caucasus and Poland are ready to join the proletariat of St. Petersburg. The slogan of the workers has become: Death or Freedom!

—Lenin on the Revolution of 1905[89]

In response to the revolution of 1905, which had failed to overthrow the government, Tsar Nicholas II accepted a series of liberal reforms in his October Manifesto. In this climate, Lenin felt it safe to return to St. Petersburg.[90] Joining the editorial board of Novaya Zhizn (New Life), a radical legal newspaper run by Maria Andreyeva, he used it to discuss issues facing the RSDLP.[91] He encouraged the party to seek out a much wider membership, and advocated the continual escalation of violent confrontation, believing both to be necessary for a successful revolution.[92] Recognising that membership fees and donations from a few wealthy sympathisers were insufficient to finance the Bolsheviks’ activities, Lenin endorsed the idea of robbing post offices, railway stations, trains, and banks. Under the lead of Leonid Krasin, a group of Bolsheviks began carrying out such criminal actions, the best known taking place in June 1907, when a group of Bolsheviks acting under the leadership of Joseph Stalin committed an armed robbery of the State Bank in Tiflis, Georgia.[93]

Although he briefly supported the idea of reconciliation between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks,[94] Lenin’s advocacy of violence and robbery was condemned by the Mensheviks at the Fourth RSDLP Congress, held in Stockholm in April 1906.[95] Lenin was involved in setting up a Bolshevik Centre in Kuokkala, Grand Duchy of Finland, which was at the time a semi-autonomous part of the Russian Empire, before the Bolsheviks regained dominance of the RSDLP at its Fifth Congress, held in London in May 1907.[96] As the Tsarist government cracked down on opposition, both by disbanding Russia’s legislative assembly, the Second Duma, and by ordering its secret police, the Okhrana, to arrest revolutionaries, Lenin fled Finland for Switzerland.[97] There, he tried to exchange those banknotes stolen in Tiflis that had identifiable serial numbers on them.[98]

Alexander Bogdanov and other prominent Bolsheviks decided to relocate the Bolshevik Centre to Paris; although Lenin disagreed, he moved to the city in December 1908.[99] Lenin disliked Paris, lambasting it as «a foul hole», and while there he sued a motorist who knocked him off his bike.[100] Lenin became very critical of Bogdanov’s view that Russia’s proletariat had to develop a socialist culture in order to become a successful revolutionary vehicle. Instead, Lenin favoured a vanguard of socialist intelligentsia who would lead the working-classes in revolution. Furthermore, Bogdanov, influenced by Ernest Mach, believed that all concepts of the world were relative, whereas Lenin stuck to the orthodox Marxist view that there was an objective reality independent of human observation.[101] Bogdanov and Lenin holidayed together at Maxim Gorky’s villa in Capri in April 1908;[102] on returning to Paris, Lenin encouraged a split within the Bolshevik faction between his and Bogdanov’s followers, accusing the latter of deviating from Marxism.[103]

In May 1908, Lenin lived briefly in London, where he used the British Museum Reading Room to write Materialism and Empirio-criticism, an attack on what he described as the «bourgeois-reactionary falsehood» of Bogdanov’s relativism.[104] Lenin’s factionalism began to alienate increasing numbers of Bolsheviks, including his former close supporters Alexei Rykov and Lev Kamenev.[105] The Okhrana exploited his factionalist attitude by sending a spy, Roman Malinovsky, to act as a vocal Lenin supporter within the party. Various Bolsheviks expressed their suspicions about Malinovsky to Lenin, although it is unclear if the latter was aware of the spy’s duplicity; it is possible that he used Malinovsky to feed false information to the Okhrana.[106]

In August 1910, Lenin attended the Eighth Congress of the Second International, an international meeting of socialists, in Copenhagen as the RSDLP’s representative, following this with a holiday in Stockholm with his mother.[107] With his wife and sisters he then moved to France, settling first in Bombon and then Paris.[108] Here, he became a close friend to the French Bolshevik Inessa Armand; some biographers suggest that they had an extra-marital affair from 1910 to 1912.[109] Meanwhile, at a Paris meeting in June 1911, the RSDLP Central Committee decided to move their focus of operations back to Russia, ordering the closure of the Bolshevik Centre and its newspaper, Proletari.[110] Seeking to rebuild his influence in the party, Lenin arranged for a party conference to be held in Prague in January 1912, and although 16 of the 18 attendants were Bolsheviks, he was heavily criticised for his factionalist tendencies and failed to boost his status within the party.[111]

Moving to Kraków in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, a culturally Polish part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he used Jagiellonian University’s library to conduct research.[112] He stayed in close contact with the RSDLP, which was operating in the Russian Empire, convincing the Duma’s Bolshevik members to split from their parliamentary alliance with the Mensheviks.[113] In January 1913, Stalin, whom Lenin referred to as the «wonderful Georgian», visited him, and they discussed the future of non-Russian ethnic groups in the Empire.[114] Due to the ailing health of both Lenin and his wife, they moved to the rural town of Biały Dunajec,[115] before heading to Bern for Nadya to have surgery on her goitre.[116]

First World War: 1914–1917

The [First World] war is being waged for the division of colonies and the robbery of foreign territory; thieves have fallen out–and to refer to the defeats at a given moment of one of the thieves in order to identify the interests of all thieves with the interests of the nation or the fatherland is an unconscionable bourgeois lie.

—Lenin on his interpretation of the First World War[117]

Lenin was in Galicia when the First World War broke out.[118] The war pitted the Russian Empire against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and due to his Russian citizenship, Lenin was arrested and briefly imprisoned until his anti-Tsarist credentials were explained.[119] Lenin and his wife returned to Bern,[120] before relocating to Zürich in February 1916.[121] Lenin was angry that the German Social-Democratic Party was supporting the German war effort, which was a direct contravention of the Second International’s Stuttgart resolution that socialist parties would oppose the conflict, and saw the Second International as defunct.[122] He attended the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915 and the Kienthal Conference in April 1916,[123] urging socialists across the continent to convert the «imperialist war» into a continent-wide «civil war» with the proletariat pitted against the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.[124] In July 1916, Lenin’s mother died, but he was unable to attend her funeral.[125] Her death deeply affected him, and he became depressed, fearing that he too would die before seeing the proletarian revolution.[126]

In September 1917, Lenin published Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, which argued that imperialism was a product of monopoly capitalism, as capitalists sought to increase their profits by extending into new territories where wages were lower and raw materials cheaper. He believed that competition and conflict would increase and that war between the imperialist powers would continue until they were overthrown by proletariat revolution and socialism established.[127] He spent much of this time reading the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Aristotle, all of whom had been key influences on Marx.[128] This changed Lenin’s interpretation of Marxism; whereas he once believed that policies could be developed based on predetermined scientific principles, he concluded that the only test of whether a policy was correct was its practice.[129] He still perceived himself as an orthodox Marxist, but he began to diverge from some of Marx’s predictions about societal development; whereas Marx had believed that a «bourgeoisie-democratic revolution» of the middle-classes had to take place before a «socialist revolution» of the proletariat, Lenin believed that in Russia the proletariat could overthrow the Tsarist regime without an intermediate revolution.[130]

February Revolution and the July Days: 1917

In February 1917, the February Revolution broke out in St. Petersburg, renamed Petrograd at the beginning of the First World War, as industrial workers went on strike over food shortages and deteriorating factory conditions. The unrest spread to other parts of Russia, and fearing that he would be violently overthrown, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated. The State Duma took over control of the country, establishing the Russian Provisional Government and converting the Empire into a new Russian Republic.[131] When Lenin learned of this from his base in Switzerland, he celebrated with other dissidents.[132] He decided to return to Russia to take charge of the Bolsheviks but found that most passages into the country were blocked due to the ongoing conflict. He organised a plan with other dissidents to negotiate a passage for them through Germany, with which Russia was then at war. Recognising that these dissidents could cause problems for their Russian enemies, the German government agreed to permit 32 Russian citizens to travel by train through their territory, among them Lenin and his wife.[133] For political reasons, Lenin and the Germans agreed to a cover story that Lenin had travelled by sealed train carriage through German territory, but in fact the train was not truly sealed, and the passengers were allowed to disembark to, for example, spend the night in Frankfurt.[134] The group travelled by train from Zürich to Sassnitz, proceeding by ferry to Trelleborg, Sweden, and from there to the Haparanda–Tornio border crossing and then to Helsinki before taking the final train to Petrograd in disguise.[135]

Lenin’s travel route from Zurich to St. Petersburg, named Petrograd at the time, in April 1917, including the ride in a so-called «sealed train» through German territory

The engine that pulled the train on which Lenin arrived at Petrograd’s Finland Station in April 1917 was not preserved. So Engine #293, by which Lenin escaped to Finland and then returned to Russia later in the year, serves as the permanent exhibit, installed at a platform on the station.[136]

Arriving at Petrograd’s Finland Station in April, Lenin gave a speech to Bolshevik supporters condemning the Provisional Government and again calling for a continent-wide European proletarian revolution.[137] Over the following days, he spoke at Bolshevik meetings, lambasting those who wanted reconciliation with the Mensheviks and revealing his «April Theses», an outline of his plans for the Bolsheviks, which he had written on the journey from Switzerland.[138] He publicly condemned both the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries, who dominated the influential Petrograd Soviet, for supporting the Provisional Government, denouncing them as traitors to socialism. Considering the government to be just as imperialist as the Tsarist regime, he advocated immediate peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary, rule by soviets, the nationalisation of industry and banks, and the state expropriation of land, all with the intention of establishing a proletariat government and pushing toward a socialist society. By contrast, the Mensheviks believed that Russia was insufficiently developed to transition to socialism, and accused Lenin of trying to plunge the new Republic into civil war.[139] Over the coming months Lenin campaigned for his policies, attending the meetings of the Bolshevik Central Committee, prolifically writing for the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda, and giving public speeches in Petrograd aimed at converting workers, soldiers, sailors, and peasants to his cause.[140]

Sensing growing frustration among Bolshevik supporters, Lenin suggested an armed political demonstration in Petrograd to test the government’s response.[141] Amid deteriorating health, he left the city to recuperate in the Finnish village of Neivola.[142] The Bolsheviks’ armed demonstration, the July Days, took place while Lenin was away, but upon learning that demonstrators had violently clashed with government forces, he returned to Petrograd and called for calm.[143] Responding to the violence, the government ordered the arrest of Lenin and other prominent Bolsheviks, raiding their offices, and publicly alleging that he was a German agent provocateur.[144] Evading arrest, Lenin hid in a series of Petrograd safe houses.[145] Fearing that he would be killed, Lenin and fellow senior Bolshevik Grigory Zinoviev escaped Petrograd in disguise, relocating to Razliv.[146] There, Lenin began work on the book that became The State and Revolution, an exposition on how he believed the socialist state would develop after the proletariat revolution, and how from then on the state would gradually wither away, leaving a pure communist society.[147] He began arguing for a Bolshevik-led armed insurrection to topple the government, but at a clandestine meeting of the party’s central committee this idea was rejected.[148] Lenin then headed by train and by foot to Finland, arriving at Helsinki on 10 August, where he hid away in safe houses belonging to Bolshevik sympathisers.[149]

October Revolution: 1917

In August 1917, while Lenin was in Finland, General Lavr Kornilov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, sent troops to Petrograd in what appeared to be a military coup attempt against the Provisional Government. Premier Alexander Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet, including its Bolshevik members, for help, allowing the revolutionaries to organise workers as Red Guards to defend the city. The coup petered out before it reached Petrograd, but the events had allowed the Bolsheviks to return to the open political arena.[150] Fearing a counter-revolution from right-wing forces hostile to socialism, the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries who dominated the Petrograd Soviet had been instrumental in pressuring the government to normalise relations with the Bolsheviks.[151] Both the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries had lost much popular support because of their affiliation with the Provisional Government and its unpopular continuation of the war. The Bolsheviks capitalised on this, and soon the pro-Bolshevik Marxist Trotsky was elected leader of the Petrograd Soviet.[152] In September, the Bolsheviks gained a majority in the workers’ sections of both the Moscow and Petrograd Soviets.[153]

Recognising that the situation was safer for him, Lenin returned to Petrograd.[154] There he attended a meeting of the Bolshevik Central Committee on 10 October, where he again argued that the party should lead an armed insurrection to topple the Provisional Government. This time the argument won with ten votes against two.[155] Critics of the plan, Zinoviev and Kamenev, argued that Russian workers would not support a violent coup against the regime and that there was no clear evidence for Lenin’s assertion that all of Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.[156] The party began plans to organise the offensive, holding a final meeting at the Smolny Institute on 24 October.[157] This was the base of the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC), an armed militia largely loyal to the Bolsheviks that had been established by the Petrograd Soviet during Kornilov’s alleged coup.[158]

In October, the MRC was ordered to take control of Petrograd’s key transport, communication, printing and utilities hubs, and did so without bloodshed.[159] Bolsheviks besieged the government in the Winter Palace, and overcame it and arrested its ministers after the cruiser Aurora, controlled by Bolshevik seamen, fired a blank shot to signal the start of the revolution.[160] During the insurrection, Lenin gave a speech to the Petrograd Soviet announcing that the Provisional Government had been overthrown.[161] The Bolsheviks declared the formation of a new government, the Council of People’s Commissars, or Sovnarkom. Lenin initially turned down the leading position of Chairman, suggesting Trotsky for the job, but other Bolsheviks insisted and ultimately Lenin relented.[162] Lenin and other Bolsheviks then attended the Second Congress of Soviets on 26 and 27 October, and announced the creation of the new government. Menshevik attendees condemned the illegitimate seizure of power and the risk of civil war.[163] In these early days of the new regime, Lenin avoided talking in Marxist and socialist terms so as not to alienate Russia’s population, and instead spoke about having a country controlled by the workers.[164][dubious – discuss] Lenin and many other Bolsheviks expected proletariat revolution to sweep across Europe in days or months.[165]

Lenin’s government

Organising the Soviet government: 1917–1918

The Provisional Government had planned for a Constituent Assembly to be elected in November 1917; against Lenin’s objections, Sovnarkom agreed for the vote to take place as scheduled.[166] In the constitutional election, the Bolsheviks gained approximately a quarter of the vote, being defeated by the agrarian-focused Socialist-Revolutionaries.[167] Lenin argued that the election was not a fair reflection of the people’s will, that the electorate had not had time to learn the Bolsheviks’ political programme, and that the candidacy lists had been drawn up before the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries split from the Socialist-Revolutionaries.[168] Nevertheless, the newly elected Russian Constituent Assembly convened in Petrograd in January 1918.[169] Sovnarkom argued that it was counter-revolutionary because it sought to remove power from the soviets, but the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks denied this.[170] The Bolsheviks presented the Assembly with a motion that would strip it of most of its legal powers; when the Assembly rejected the motion, Sovnarkom declared this as evidence of its counter-revolutionary nature and forcibly disbanded it.[171]

Lenin rejected repeated calls, including from some Bolsheviks, to establish a coalition government with other socialist parties.[172] Although refusing a coalition with the Mensheviks or Socialist-Revolutionaries, Sovnarkom partially relented; they allowed the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries five posts in the cabinet in December 1917. This coalition only lasted four months until March 1918, when the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries pulled out of the government over a disagreement about the Bolsheviks’ approach to ending the First World War.[173] At their 7th Congress in March 1918, the Bolsheviks changed their official name from the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party to the Russian Communist Party, as Lenin wanted to both distance his group from the increasingly reformist German Social Democratic Party and to emphasise its ultimate goal, that of a communist society.[174]

The Moscow Kremlin, which Lenin moved into in 1918 (pictured in 1987)

Although ultimate power officially rested with the country’s government in the form of Sovnarkom and the Executive Committee (VTSIK) elected by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets (ARCS), the Communist Party was de facto in control in Russia, as acknowledged by its members at the time.[175] By 1918, Sovnarkom began acting unilaterally, claiming a need for expediency, with the ARCS and VTSIK becoming increasingly marginalised,[176] so the soviets no longer had a role in governing Russia.[177] During 1918 and 1919, the government expelled Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries from the soviets.[178] Russia had become a one-party state.[179]

Within the party was established a Political Bureau (Politburo) and Organisation Bureau (Orgburo) to accompany the existing Central Committee; the decisions of these party bodies had to be adopted by Sovnarkom and the Council of Labour and Defence.[180] Lenin was the most significant figure in this governance structure as well as being the Chairman of Sovnarkom and sitting on the Council of Labour and Defence, and on the Central Committee and Politburo of the Communist Party.[181] The only individual to have anywhere near this influence was Lenin’s right-hand man, Yakov Sverdlov, who died in March 1919 during a flu pandemic.[182] In November 1917, Lenin and his wife took a two-room flat within the Smolny Institute; the following month they left for a brief holiday in Halila, Finland.[183] In January 1918, he survived an assassination attempt in Petrograd; Fritz Platten, who was with Lenin at the time, shielded him and was injured by a bullet.[184]

Concerned that the German Army posed a threat to Petrograd, in March 1918 Sovnarkom relocated to Moscow, initially as a temporary measure.[185] There, Lenin, Trotsky, and other Bolshevik leaders moved into the Kremlin, where Lenin lived with his wife and sister Maria in a first floor apartment adjacent to the room in which the Sovnarkom meetings were held.[186] Lenin disliked Moscow,[187] but rarely left the city centre during the rest of his life.[188] He survived a second assassination attempt, in Moscow in August 1918; he was shot following a public speech and injured badly.[189] A Socialist-Revolutionary, Fanny Kaplan, was arrested and executed.[190] The attack was widely covered in the Russian press, generating much sympathy for Lenin and boosting his popularity.[191] As a respite, he was driven in September 1918 to the luxurious Gorki estate, just outside Moscow, recently nationalized for him by the government.[192]

Social, legal, and economic reform: 1917–1918

To All Workers, Soldiers and Peasants. The Soviet authority will at once propose a democratic peace to all nations and an immediate armistice on all fronts. It will safeguard the transfer without compensation of all land—landlord, imperial, and monastery—to the peasants’ committees; it will defend the soldiers’ rights, introducing a complete democratisation of the army; it will establish workers’ control over industry; it will ensure the convocation of the Constituent Assembly on the date set; it will supply the cities with bread and the villages with articles of first necessity; and it will secure to all nationalities inhabiting Russia the right of self-determination … Long live the revolution!

—Lenin’s political programme, October 1917[193]

Upon taking power, Lenin’s regime issued a series of decrees. The first was a Decree on Land, which declared that the landed estates of the aristocracy and the Orthodox Church should be nationalised and redistributed to peasants by local governments. This contrasted with Lenin’s desire for agricultural collectivisation but provided governmental recognition of the widespread peasant land seizures that had already occurred.[194] In November 1917, the government issued the Decree on the Press that closed many opposition media outlets deemed counter-revolutionary. They claimed the measure would be temporary; the decree was widely criticised, including by many Bolsheviks, for compromising freedom of the press.[195]

In November 1917, Lenin issued the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, which stated that non-Russian ethnic groups living inside the Republic had the right to secede from Russian authority and establish their own independent nation-states.[196] Many nations declared independence (Finland and Lithuania in December 1917, Latvia and Ukraine in January 1918, Estonia in February 1918, Transcaucasia in April 1918, and Poland in November 1918).[197] Soon, the Bolsheviks actively promoted communist parties in these independent nation-states,[198] while at the Fifth All-Russian Congress of the Soviets in July 1918 a constitution was approved that reformed the Russian Republic into the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[199] Seeking to modernise the country, the government officially converted Russia from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar used in Europe.[200]

In November 1917, Sovnarkom issued a decree abolishing Russia’s legal system, calling on the use of «revolutionary conscience» to replace the abolished laws.[201] The courts were replaced by a two-tier system, namely the Revolutionary Tribunals to deal with counter-revolutionary crimes,[202] and the People’s Courts to deal with civil and other criminal offences. They were instructed to ignore pre-existing laws, and base their rulings on the Sovnarkom decrees and a «socialist sense of justice.»[203] November also saw an overhaul of the armed forces; Sovnarkom implemented egalitarian measures, abolished previous ranks, titles, and medals, and called on soldiers to establish committees to elect their commanders.[204]

Bolshevik political cartoon poster from 1920, showing Lenin sweeping away monarchs, clergy, and capitalists; the caption reads, «Comrade Lenin Cleanses the Earth of Filth»

In October 1917, Lenin issued a decree limiting work for everyone in Russia to eight hours per day.[205] He also issued the Decree on Popular Education that stipulated that the government would guarantee free, secular education for all children in Russia,[205] and a decree establishing a system of state orphanages.[206] To combat mass illiteracy, a literacy campaign was initiated; an estimated 5 million people enrolled in crash courses of basic literacy from 1920 to 1926.[207] Embracing the equality of the sexes, laws were introduced that helped to emancipate women, by giving them economic autonomy from their husbands and removing restrictions on divorce.[208] Zhenotdel, a Bolshevik women’s organisation, was established to further these aims. [209] Under Lenin, Russia became the first country to legalize abortion on demand in the first trimester.[210] Militantly atheist, Lenin and the Communist Party wanted to demolish organised religion.[211] In January 1918, the government decreed the separation of church and state, and prohibited religious instruction in schools.[212]

In November 1917, Lenin issued the Decree on Workers’ Control, which called on the workers of each enterprise to establish an elected committee to monitor their enterprise’s management.[213] That month they also issued an order requisitioning the country’s gold,[214] and nationalised the banks, which Lenin saw as a major step toward socialism.[215] In December, Sovnarkom established a Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh), which had authority over industry, banking, agriculture, and trade.[216] The factory committees were subordinate to the trade unions, which were subordinate to VSNKh; the state’s centralised economic plan was prioritised over the workers’ local economic interests.[217] In early 1918, Sovnarkom cancelled all foreign debts and refused to pay interest owed on them.[218] In April 1918, it nationalised foreign trade, establishing a state monopoly on imports and exports.[219] In June 1918, it decreed nationalisation of public utilities, railways, engineering, textiles, metallurgy, and mining, although often these were state-owned in name only.[220] Full-scale nationalisation did not take place until November 1920, when small-scale industrial enterprises were brought under state control.[221]

A faction of the Bolsheviks known as the «Left Communists» criticised Sovnarkom’s economic policy as too moderate; they wanted nationalisation of all industry, agriculture, trade, finance, transport, and communication.[222] Lenin believed that this was impractical at that stage and that the government should only nationalise Russia’s large-scale capitalist enterprises, such as the banks, railways, larger landed estates, and larger factories and mines, allowing smaller businesses to operate privately until they grew large enough to be successfully nationalised.[222] Lenin also disagreed with the Left Communists about the economic organisation; in June 1918, he argued that centralised economic control of industry was needed, whereas Left Communists wanted each factory to be controlled by its workers, a syndicalist approach that Lenin considered detrimental to the cause of socialism.[223]

Adopting a left-libertarian perspective, both the Left Communists and other factions in the Communist Party critiqued the decline of democratic institutions in Russia.[224] Internationally, many socialists decried Lenin’s regime and denied that he was establishing socialism; in particular, they highlighted the lack of widespread political participation, popular consultation, and industrial democracy.[225] In late 1918, the Czech-Austrian Marxist Karl Kautsky authored an anti-Leninist pamphlet condemning the anti-democratic nature of Soviet Russia, to which Lenin published a vociferous reply.[226] German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg echoed Kautsky’s views,[227] while Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin described the Bolshevik seizure of power as «the burial of the Russian Revolution.»[228]

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk: 1917–1918

[By prolonging the war] we unusually strengthen German imperialism, and the peace will have to be concluded anyway, but then the peace will be worse because it will be concluded by someone other than ourselves. No doubt the peace which we are now being forced to conclude is an indecent peace, but if war commences our government will be swept away and the peace will be concluded by another government.

—Lenin on peace with the Central Powers[229]

Upon taking power, Lenin believed that a key policy of his government must be to withdraw from the First World War by establishing an armistice with the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary.[230] He believed that ongoing war would create resentment among war-weary Russian troops, to whom he had promised peace, and that these troops and the advancing German Army threatened both his own government and the cause of international socialism.[231] By contrast, other Bolsheviks, in particular Nikolai Bukharin and the Left Communists, believed that peace with the Central Powers would be a betrayal of international socialism and that Russia should instead wage «a war of revolutionary defence» that would provoke an uprising of the German proletariat against their own government.[232]

Lenin proposed a three-month armistice in his Decree on Peace of November 1917, which was approved by the Second Congress of Soviets and presented to the German and Austro-Hungarian governments.[233] The Germans responded positively, viewing this as an opportunity to focus on the Western Front and stave off looming defeat.[234] In November, armistice talks began at Brest-Litovsk, the headquarters of the German high command on the Eastern Front, with the Russian delegation being led by Trotsky and Adolph Joffe.[235] Meanwhile, a ceasefire until January was agreed.[236] During negotiations, the Germans insisted on keeping their wartime conquests, which included Poland, Lithuania, and Courland, whereas the Russians countered that this was a violation of these nations’ rights to self-determination.[237] Some Bolsheviks had expressed hopes of dragging out negotiations until proletarian revolution broke out throughout Europe.[238] On 7 January 1918, Trotsky returned from Brest-Litovsk to St. Petersburg with an ultimatum from the Central Powers: either Russia accept Germany’s territorial demands or the war would resume.[239]

Signing of the armistice between Russia and Germany on 15 December 1917

In January and again in February, Lenin urged the Bolsheviks to accept Germany’s proposals. He argued that the territorial losses were acceptable if it ensured the survival of the Bolshevik-led government. The majority of Bolsheviks rejected his position, hoping to prolong the armistice and call Germany’s bluff.[240] On 18 February, the German Army launched Operation Faustschlag, advancing further into Russian-controlled territory and conquering Dvinsk within a day.[241] At this point, Lenin finally convinced a small majority of the Bolshevik Central Committee to accept the Central Powers’ demands.[242] On 23 February, the Central Powers issued a new ultimatum: Russia had to recognise German control not only of Poland and the Baltic states but also of Ukraine, or face a full-scale invasion.[243]

On 3 March, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed.[244] It resulted in massive territorial losses for Russia, with 26% of the former Empire’s population, 37% of its agricultural harvest area, 28% of its industry, 26% of its railway tracks, and three-quarters of its coal and iron deposits being transferred to German control.[245] Accordingly, the Treaty was deeply unpopular across Russia’s political spectrum,[246] and several Bolsheviks and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries resigned from Sovnarkom in protest.[247] After the Treaty, Sovnarkom focused on trying to foment proletarian revolution in Germany, issuing an array of anti-war and anti-government publications in the country; the German government retaliated by expelling Russia’s diplomats.[248] The Treaty nevertheless failed to stop the Central Powers’ defeat; in November 1918, the German Emperor Wilhelm II abdicated and the country’s new administration signed the Armistice with the Allies. As a result, Sovnarkom proclaimed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk void.[249]

Anti-Kulak campaigns, Cheka, and Red Terror: 1918–1922

[The bourgeoisie] practised terror against the workers, soldiers and peasants in the interests of a small group of landowners and bankers, whereas the Soviet regime applies decisive measures against landowners, plunderers and their accomplices in the interests of the workers, soldiers and peasants.

—Lenin on the Red Terror[250]

By early 1918, many cities in western Russia faced famine as a result of chronic food shortages.[251] Lenin blamed this on the kulaks, or wealthier peasants, who allegedly hoarded the grain that they had produced to increase its financial value. In May 1918, he issued a requisitioning order that established armed detachments to confiscate grain from kulaks for distribution in the cities, and in June called for the formation of Committees of Poor Peasants to aid in requisitioning.[252] This policy resulted in vast social disorder and violence, as armed detachments often clashed with peasant groups, helping to set the stage for the civil war.[253] A prominent example of Lenin’s views was his August 1918 telegram to the Bolsheviks of Penza, which called upon them to suppress a peasant insurrection by publicly hanging at least 100 «known kulaks, rich men, [and] bloodsuckers.»[254]

The requisitions disincentivised peasants from producing more grain than they could personally consume, and thus production slumped.[255] A booming black market supplemented the official state-sanctioned economy,[256] and Lenin called on speculators, black marketeers and looters to be shot.[257] Both the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries condemned the armed appropriations of grain at the Fifth All-Russian Congress of Soviets in July 1918.[258] Realising that the Committees of the Poor Peasants were also persecuting peasants who were not kulaks and thus contributing to anti-government feeling among the peasantry, in December 1918 Lenin abolished them.[259]

Lenin repeatedly emphasised the need for terror and violence in overthrowing the old order and ensuring the success of the revolution.[260] Speaking to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets in November 1917, he declared that «the state is an institution built up for the sake of exercising violence. Previously, this violence was exercised by a handful of moneybags over the entire people; now we want […] to organise violence in the interests of the people.»[261] He strongly opposed suggestions to abolish capital punishment.[262] Fearing anti-Bolshevik forces would overthrow his administration, in December 1917 Lenin ordered the establishment of the Emergency Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, or Cheka, a political police force led by Felix Dzerzhinsky.[263]

Lenin with his wife and sister in a car after watching a Red Army parade at Khodynka Field in Moscow, May Day 1918

In September 1918, Sovnarkom passed a decree that inaugurated the Red Terror, a system of repression orchestrated by the Cheka secret police.[264] Although sometimes described as an attempt to eliminate the entire bourgeoisie,[265] Lenin did not want to exterminate all members of this class, merely those who sought to reinstate their rule.[266] The majority of the Terror’s victims were well-to-do citizens or former members of the Tsarist administration;[267] others were non-bourgeois anti-Bolsheviks and perceived social undesirables such as prostitutes.[268] The Cheka claimed the right to both sentence and execute anyone whom it deemed to be an enemy of the government, without recourse to the Revolutionary Tribunals.[269] Accordingly, throughout Soviet Russia the Cheka carried out killings, often in large numbers.[270] For example, the Petrograd Cheka executed 512 people in a few days.[271] There are no surviving records to provide an accurate figure of how many perished in the Red Terror;[272] later estimates of historians have ranged between 10,000 and 15,000,[273] and 50,000 to 140,000.[274]