Время на прочтение

14 мин

Количество просмотров 45K

В этой статье:

-

Узнаем, что такое логическое программирование (ЛП), и его области применения

-

Установим самый популярный язык ЛП — Prolog

-

Научимся писать простые программы на Prolog

-

Научимся спискам в Prolog

-

Разберем преимущества и недостатки Prolog.

Эта статья будет полезна для тех, кто:

-

Интересуется необычными подходами и расширяет свой кругозор

-

Начинает изучать Prolog (например, в институте)

Меня зовут Михаил Горохов, и эта статья написана в рамках вузовского курсового проекта. В первую очередь эта статья ориентирована на студентов ПМ и ПМИ, на долю которых выпало изучение прекрасного мощного языка Prolog, и которым приходится изучать совершенно новый и непривычный для них подход. Первое время он даже голову ломает. Особенно любителям оптимизации.

В конце статьи я оставлю полезные ссылки. Если у вас останутся вопросы — пишите в комментариях!

Начнем туториал: Пролог для чайников!

Логическое программирование

Существуют разные подходы к программированию. Часто выделяют такие парадигмы программирования:

-

Императивное (оно же алгоритмическое или процедурное). Самая известная парадигма. Программист четко прописывает последовательность команд, которые должен выполнить процессор. Примеры: C/C++, Java, C#, Python, Golang, машина Тюрьнга, алгоритмы Маркова. Все четко, последовательно

как надо. Синоним императивного — приказательное. -

Аппликативное (Функциональное). Менее известная, но тоже широко используемая. Примеры языков: Haskell, F#, Лисп. Основывается на математической абстракции лямбда вычислениях. Благодаря чистым функциям очень удобно параллелить такие программы. Чистые функции — функции без побочных эффектов. Если такой функции передавать одни и те же аргументы, то результат всегда будет один и тот же. Такие языки обладают высокой надежностью кода.

-

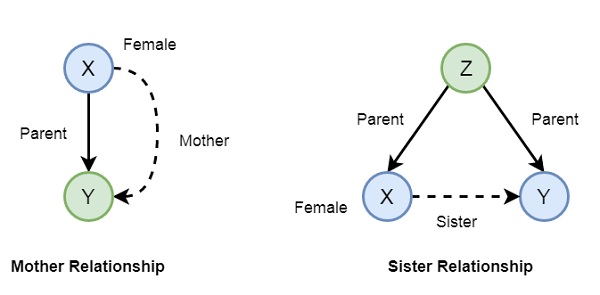

И наконец — Декларативное (Логическое). Основывается на автоматическом доказательстве теорем на основе фактов и правил. Примеры языков: Prolog и его диалекты, Mercury. В таких языках мы описываем пространство состояний, в которых сам язык ищет решение к задаче. Мы просто даем ему правила, факты, а потом говорим, что «сочини все возможные стихи из этих слов», «реши логическую задачу», «найди всех братьев, сестер, золовок, свояков в генеалогическом древе», или «раскрась граф наименьшим кол-вом цветов так, что смежные ребра были разного цвета».

Что такое ЛП я обозначил. Предлагаю сразу перейти к практике, к основам Prolog (PROgramming in LOGic). На практике все становится понятнее. Практику и теорию я буду чередовать. Не беспокойтесь, если сразу будет что-то не понятно. Повторяйте за мной, и вы разберетесь.

Установка Prolog

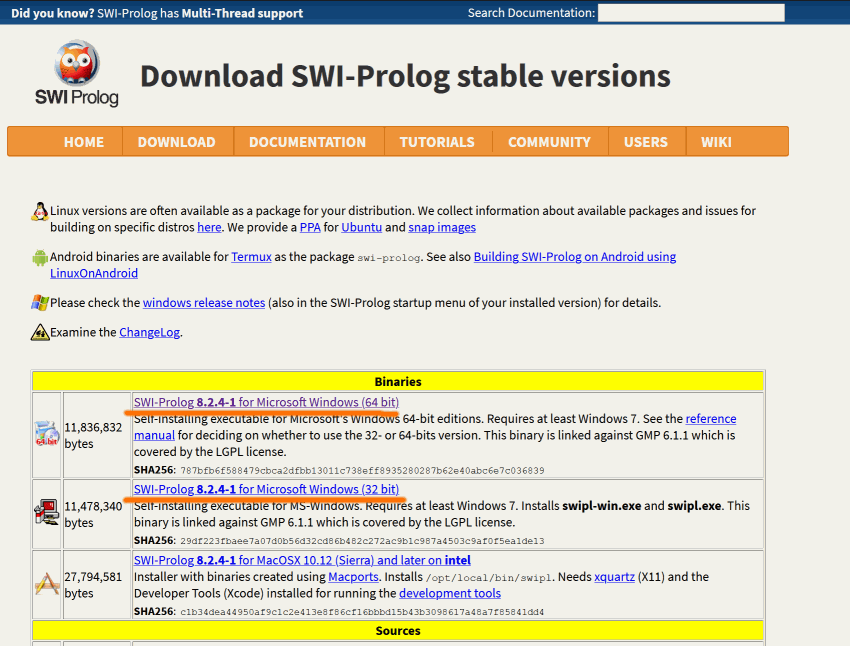

Существую разные реализации (имплементации) Пролога: SWI Prolog, Visual Prolog, GNU Prolog. Мы установим SWI Prolog.

Установка на Arch Linux:

sudo pacman -S swi-prologУстановка на Ubuntu:

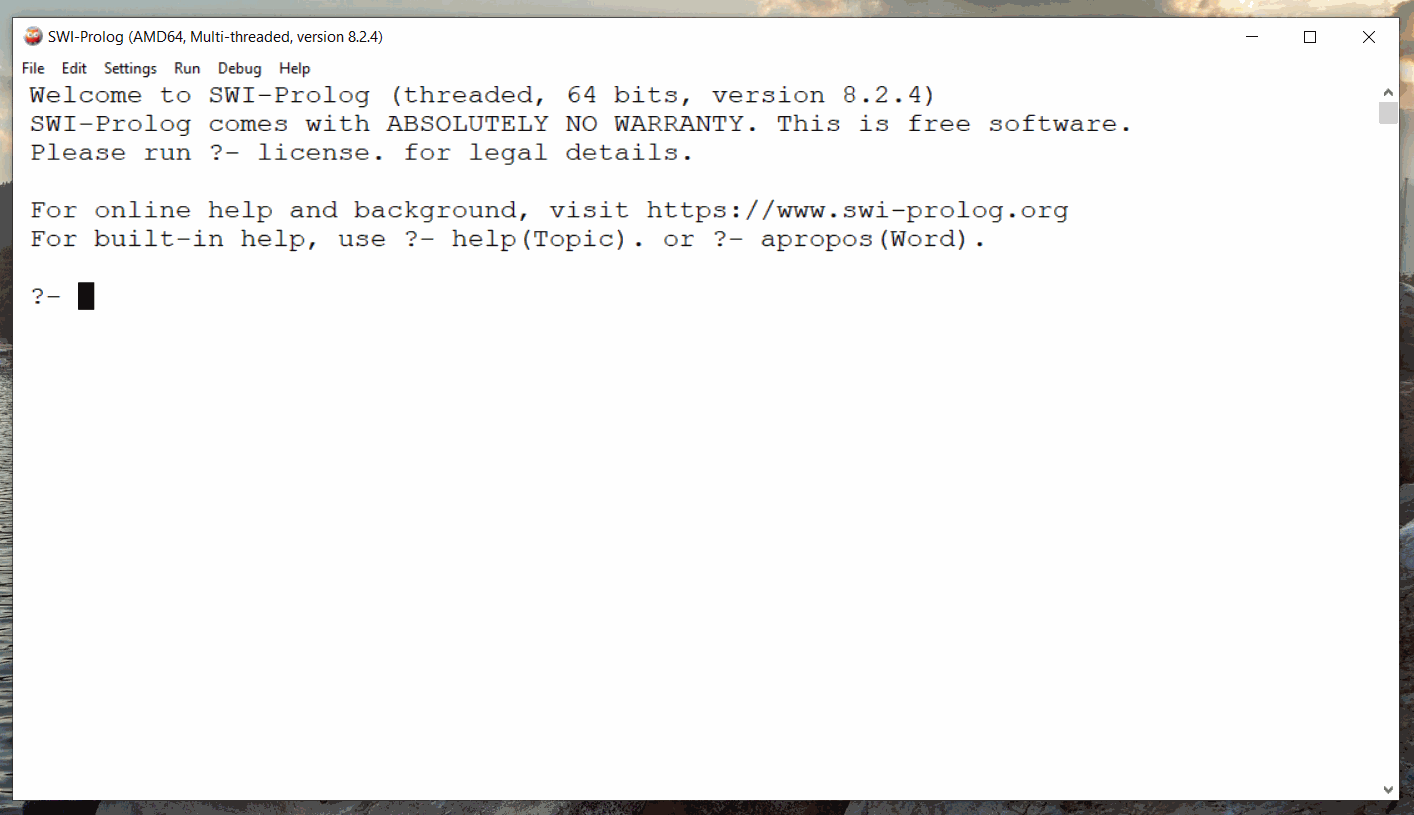

sudo apt install swi-prologProlog работает в режиме интерпретатора. Теперь можем запустить SWI Prolog. Запускать не через swi-prolog, а через swipl:

[user@Raft ~]$ swipl

Welcome to SWI-Prolog (threaded, 64 bits, version 8.2.3)

SWI-Prolog comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY. This is free software.

Please run ?- license. for legal details.

For online help and background, visit https://www.swi-prolog.org

For built-in help, use ?- help(Topic). or ?- apropos(Word).

?- Ура! Оно работает!

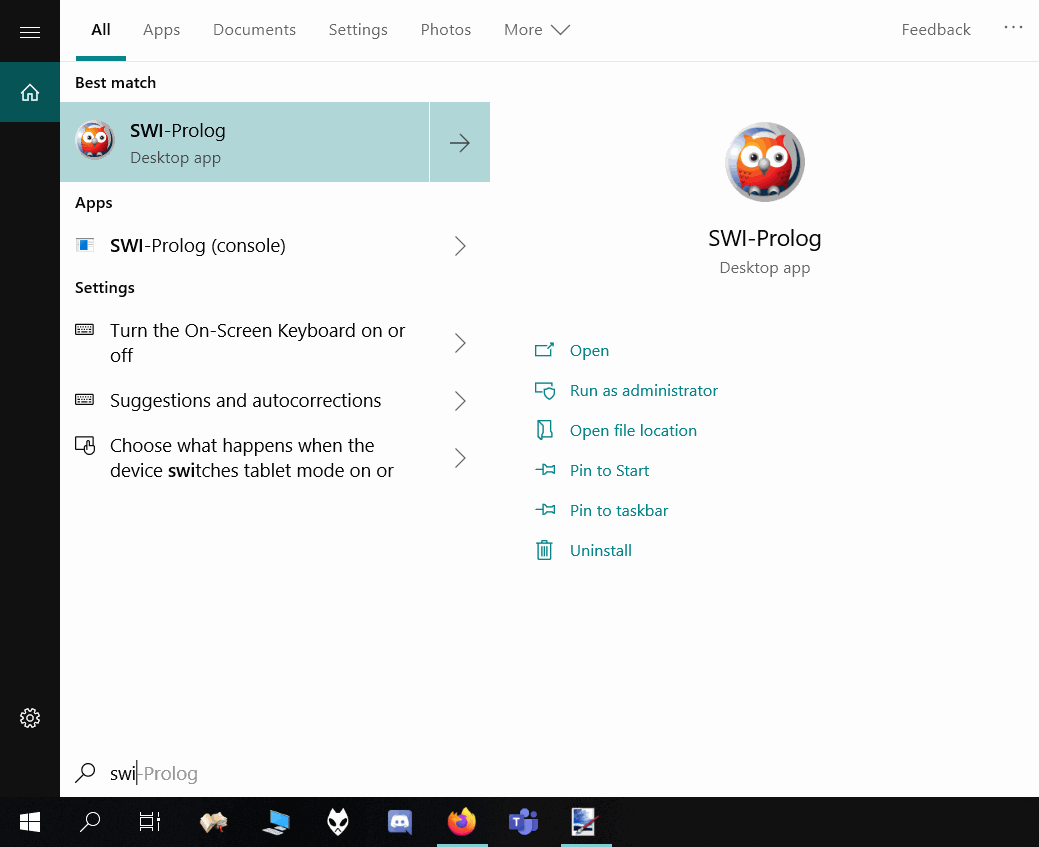

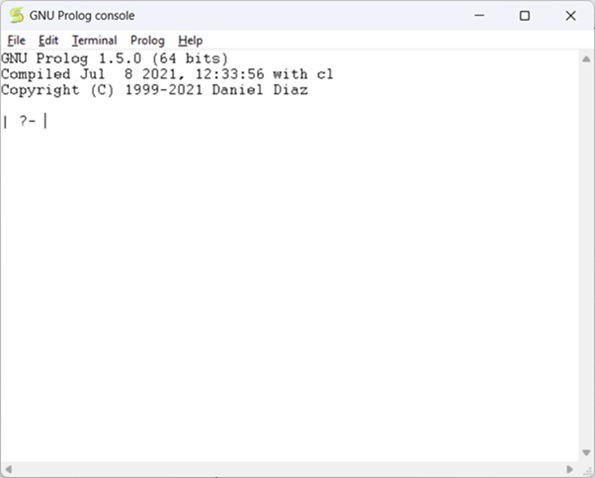

Теперь поставим на Windows.

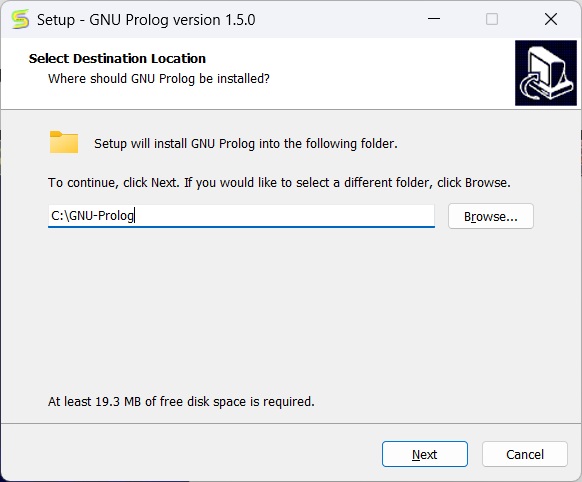

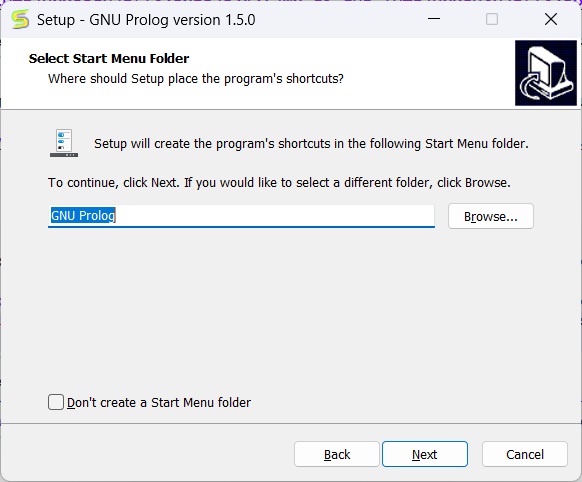

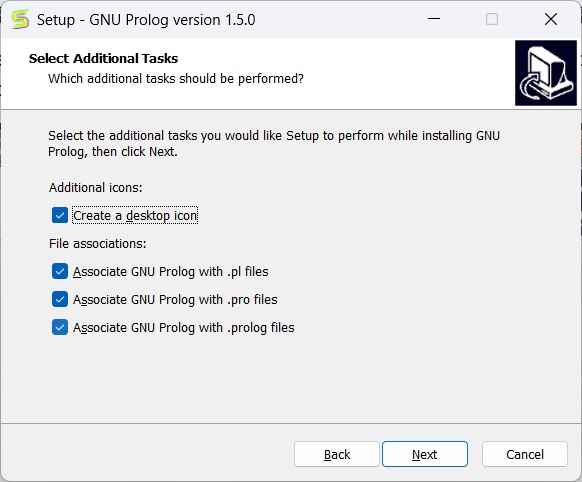

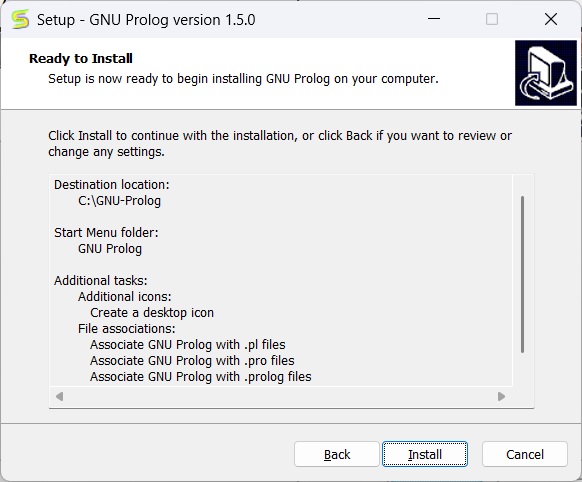

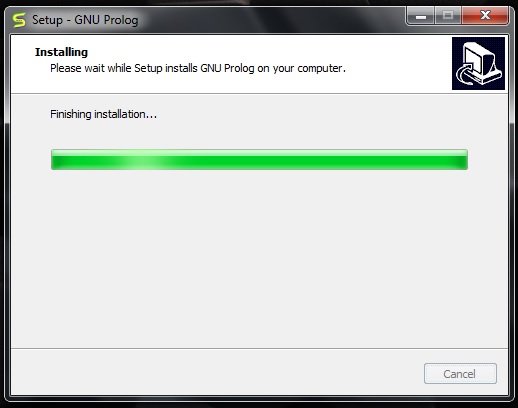

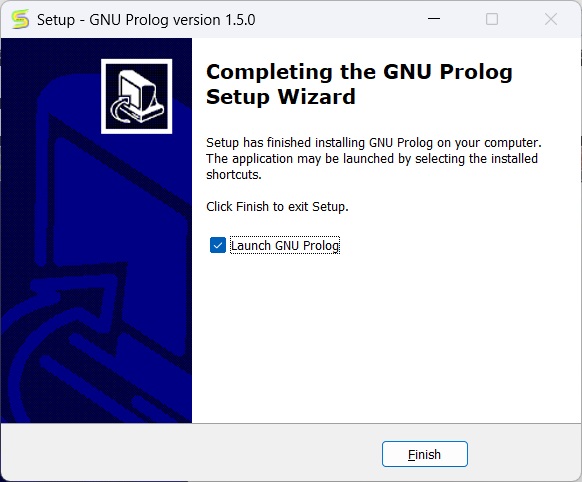

Перейдем на официальный сайт на страницу скачивания стабильной версии. Ссылка на скачивание. Клик. Скачаем 64х битную версию. Установка стандартная. Чтобы ничего не сломать, я решил галочки не снимать. Ради приличия я оставлю скрины установки.

Основы Prolog. Факты, правила, предикаты

Есть утверждения, предикаты:

-

Марк изучает книгу (учебник, документацию)

-

Маша видит клавиатуру (мышку, книгу, тетрадь, Марка)

-

Миша изучает математику (ЛП, документацию, учебник)

-

Саша старше Лёши

С английского «predicate» означает «логическое утверждение».

Есть объекты: книга, клавиатура, мышка, учебник, документация, тетрадь, математика, ЛП, Марк, Маша, Саша, Даша, Лёша, Миша, да что угодно может быть объектом.

Есть отношения между объектами, т.е то, что связывает объекты. Связь объектов можно выразить через глаголы, например: читать, видеть, изучать. Связь можно выразить через прилагательное. Миша старше Даши. Даша старше Лёши. Получается.. связью может быть любая часть речь? Получается так.

Прекрасно! Давайте попробуем запрограммировать эти утверждения на Прологе. Для этого нам нужно:

-

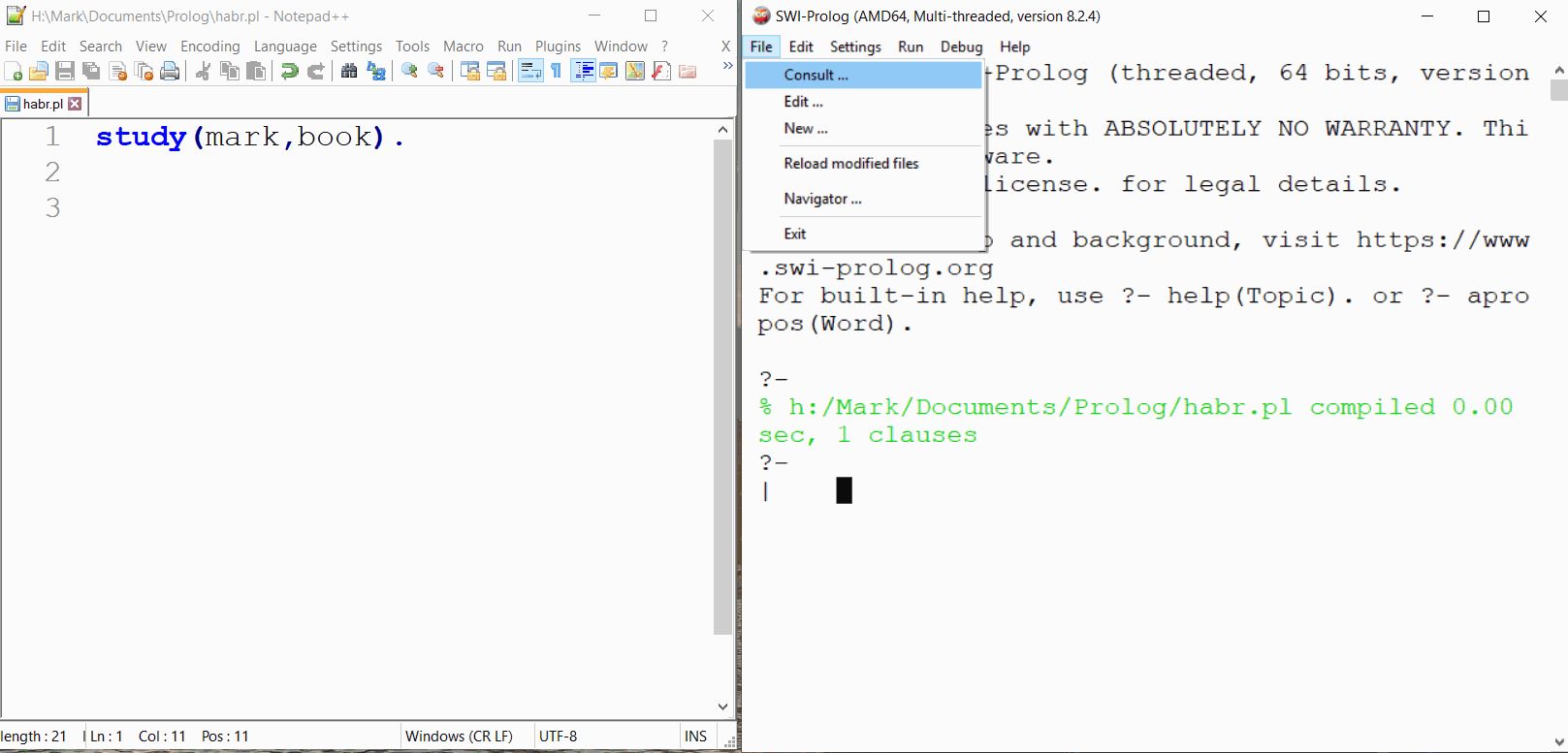

Создать новый текстовый файл, который я назову simple.pl (.pl — расширение Пролога)

-

В нем написать простой однострочный код на Прологе

-

Запустить код с помощью SWI Prolog

-

Спросить у Пролога этот факт

Файл simple.pl:

study(mark, book).Запустим. На линуксе это делается таким образом:

[user@Raft referat]$ swipl simple.pl

Welcome to SWI-Prolog (threaded, 64 bits, version 8.2.3)

SWI-Prolog comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY. This is free software.

Please run ?- license. for legal details.

For online help and background, visit https://www.swi-prolog.org

For built-in help, use ?- help(Topic). or ?- apropos(Word).

?- На Windows я использую notepad++ для написания кода на Прологе. Я запущу SWI-Prolog и открою файл через consult.

Что мы сделали? Мы загрузили базу знаний (те, которые мы описали в простом однострочном файле simple.pl) и теперь можем задавать вопросы Прологу. То есть система такая: пишем знания в файле, загружаем эти знания в SWI Prolog и задаем вопросы интерпретатору. Так мы будем решать поставленную задачу. (Даже видно, в начале интерпретатор пишет «?- «. Это означает, что он ждет нашего вопроса, как великий мистик)

Давайте спросим «Марк изучает книгу?» На Прологе это выглядит так:

?- study(mark, book).

true.

?- По сути мы спросили «есть ли факт study(mark, study) в твоей базе?», на что нам Пролог лаконично ответил «true.» и продолжает ждать следующего вопроса. А давайте спросим, «изучает ли Марк документацию?»

?- study(mark, book).

true.

?- study(mark, docs).

false.

?- Интерпретатор сказал «false.». Это означает, что он не нашел этот факт в своей базе фактов.

Расширим базу фактов. После я определю более строгую терминологию и опишу, что происходит в этом коде.

Сделаю важное замечание для начинающих. Сложность Пролога состоит в специфичной терминологии и в непривычном синтаксисе, в отсутствии императивных фич, вроде привычного присвоения переменных.

% Код на прологе. Я описал 11 фактов.

% Каждый факт оканчивается точкой ".", как в русском языке, как любое утверждение.

% Комментарии начинаются с "%".

% Интерпретатор пролога игнорирует такие комментарии.

/* А это

многострочный

комментарий

*/

% Факты. 11 штук

study(mark, book). % Марк изучает книгу

study(mark, studentbook). % Марк изучает учебник

study(mark, docs). % Марк изучает доки

see(masha, mouse). % Маша видит мышь

see(masha, book). % Маша видит книгу

see(masha, notebook). % Маша видит тетрадь

see(masha, mark). % Маша видит Марка

study(misha, math). % Миша изучает матешу

study(misha, lp). % Миша изучает пролог

study(misha, docs). % Миша изучает доки

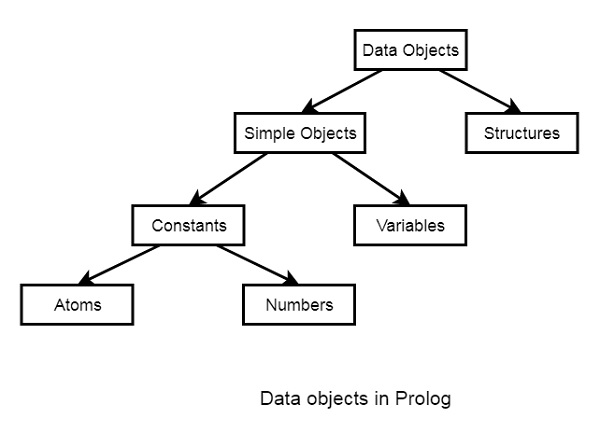

study(misha, studentbook). % Миша изучает учебникТерминология. Объекты данных в Прологе называются термами (предполагаю, от слова «термин»). Термы бывают следующих видов:

-

Константами. Делятся на числа и атомы. Начинаются с маленькой буквы. Числа: 1,36, 0, -1, 123.4, 0.23E-5. Атомы — это просто символы и строки: a, abc, neOdinSimvol, sTROKa. Если атом состоит из пробела, запятых и тд, то нужно их обрамлять в одинарные кавычки. Пример атома: ‘строка с пробелами, запятыми. Eto kirilicca’.

-

Переменными. Начинаются с заглавной буквы: X, Y, Z, Peremennaya, Var.

-

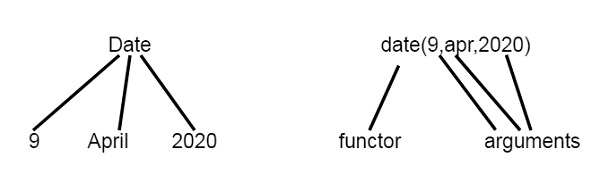

Структурами (сложные термы). Например, study(misha, lp).

-

Списками. Пример: [X1], [Head|Tail]. Мы разберем их позже в этой статье.

Есть хорошая статья, которая подробно рассказывает про синтаксис и терминологию Пролога. Рекомендую её, чтобы лучше понять понятия Пролог.

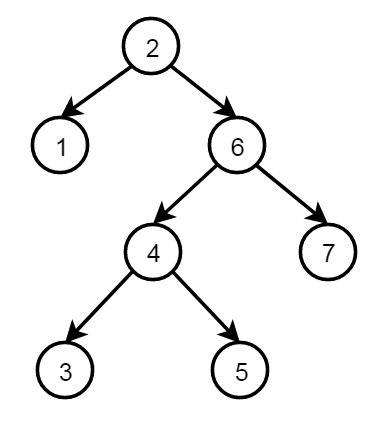

Пролог использует методы полного перебора и обход дерева. Во время проверки условий (доказательства утверждений) Пролог заменяет переменные на конкретные значения. Через пару абзацев будут примеры.

study(mark, book). — такие конструкции называются фактами. Они всегда истинны. Если факта в базе знаний нету, то такой факт ложный. Факты нужно оканчивать точкой, так же как утверждения в русском языке.

«Задавать вопросы Прологу» означает попросить Пролог доказать наше утверждение. Пример: ?- study(mark, book). Если наше утверждение всегда истинно, то Пролог напечатает true, если всегда ложно, то false. Если наше утверждение верно при некоторых значениях переменных, то Пролог выведет значения переменных, при которых наше утверждение верно.

Давайте загрузим факты в Пролог и будем задавать вопросы. Давайте узнаем, что изучал mark. Для этого нам нужно написать «study(mark, X).» Если мы прожмем «Enter«, то Пролог нам выдаст первое попавшееся решение

?- study(mark, X).

X = book .Чтобы получить все возможные решения, нужно прожимать точку с запятой «;«.

?- study(mark, X).

X = book ;

X = studentbook ;

X = docs.Можем узнать, кто изучал документацию.

?- study(Who, docs).

Who = mark ;

Who = misha.Можно узнать, кто и что изучал!

?- study(Who, Object).

Who = mark,

Object = book ;

Who = mark,

Object = studentbook ;

Who = mark,

Object = docs ;

Who = misha,

Object = math ;

Who = misha,

Object = lp ;

Who = misha,

Object = docs ;

Who = misha,

Object = studentbook.Пролог проходится по всей базе фактов и находит все такие переменные Who и Object, что предикат study(Who, Object) будет истинным. Пролог перебирает факты и заменяет переменные на конкретные значения. Пролог выведет такие значения переменных, при которых утверждения будут истинными. У нас задача состояла только из фактов, и решение получилось очевидным.

Переменная Who перебирается среди имен mark, misha, а переменная Object среди book, studentbook, docs, lp, math.

Who не может равняться masha, потому что masha ничего не узнала согласно нашей базе фактов. Аналогично Object не может равняться tomuChevoNetuVBaze, так как такого значения не было в базе фактов. Для study на втором месте были только book, studentbook, docs, lp, math.

Короче, я старался понятным языком объяснить метод полного перебора, и что Пролог тупо все перебирает, пока что-то не подойдет. Все просто.

А теперь разберем правила в Прологе. Напишем ещё одну программу old.pl.

% Это факты

older(sasha, lesha). % Саша старше Лёши

older(misha, sasha). % Миша старше Саши

older(misha, dasha). % Миша старше Даши

older(masha, misha). % Маша старше Миши

% Это правило

older(X,Y) :- older(X, Z), older(Z,Y).

% X старше Y, если X старше Z и Z старше Y

% Проще: X > Y, если X > Z и Z > Y

%

% X, Y, Z - это переменные.

% Вместо X, Y, Z подставляются конкретные значения: misha, dasha, sasha, lesha

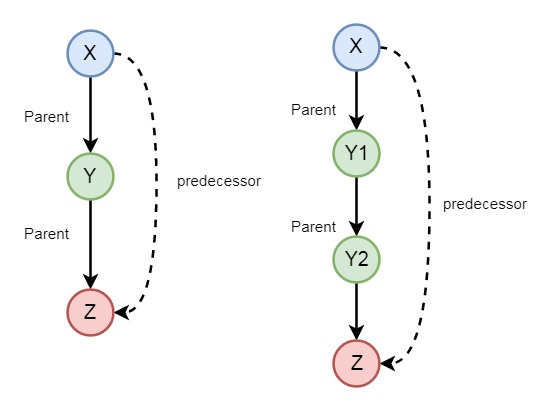

% Main idea: если Пролог найдет среднего Z, который между X и Y, то X старше Y.older(X,Y) :- older(X, Z), older(Z,Y) — такие конструкции называются правилами. Чтобы из факта получить правило, нужно заменить точку «.» на двоеточие дефис «:-» и написать условие, когда правило будет истинным. Правила истинны только при определенных условиях. Например, это правило будет истинно в случае, когда факты older(X,Z) и older(Z,Y) истинны. Если переформулировать, то получается «X старше Y, если X старше Z и Z старше Y». Если математически: «X > Y, если X > Z и Z > Y».

Запятая «,» в Прологе играет роль логического «И». Пример: «0 < X, X < 5». X меньше 5 И больше 0.

Точка с запятой «;» играет роль логического «ИЛИ». «X < 0; X > 5». X меньше 0 ИЛИ больше 5.

Отрицание «not(Какой-нибудь предикат)» играет роль логического «НЕ». «not(X==5)». X НЕ равен 5.

Факты и правила образуют утверждения, предикаты. (хорошая статья про предикаты)

Сперва закомментируйте правило и поспрашивайте Пролог, кто старше кого.

?- older(masha, X).

X = misha.Маша старше Миши. Пролог просто прошелся по фактам и нашел единственное верный факт. Но.. мы хотели узнать «Кого старше Маша?». Логично же, что если Миша старше Саши И Маша старше Миши, то Маша также старше Саши. И Пролог должен решать такие логические задачи. Поэтому нужно добавить правило older(X,Y) :- older(X, Z), older(Z,Y).

Повторим вопрос.

?- older(masha, X).

X = misha ;

X = sasha ;

X = dasha ;

X = lesha ;

ERROR: Stack limit (1.0Gb) exceeded

ERROR: Stack sizes: local: 1.0Gb, global: 21Kb, trail: 1Kb

ERROR: Stack depth: 12,200,525, last-call: 0%, Choice points: 6

ERROR: Probable infinite recursion (cycle):

ERROR: [12,200,525] user:older(lesha, _5658)

ERROR: [12,200,524] user:older(lesha, _5678)

?- Программа смогла найти все решения. Но что это такое? Ошибка! Стек переполнен! Как вы думаете, с чем это может быть связано? Попробуйте подумать, почему это происходит. Хорошее упражнение — расписать на бумаге алгоритм older(masha,X) так, как будто вы — Пролог. Видите причину ошибки?

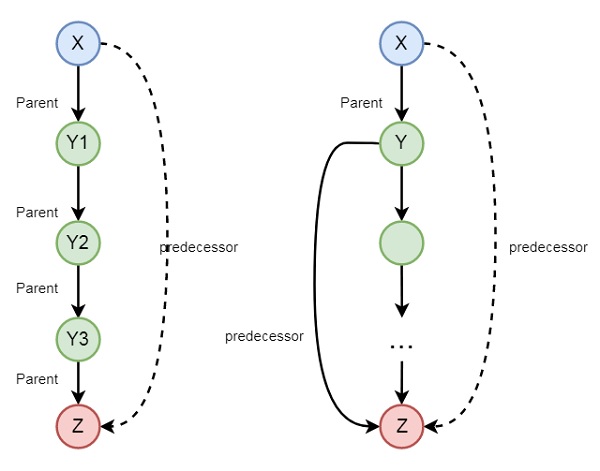

Это связано с бесконечной рекурсией. Это частая ошибка, которая возникает в программировании, в частности, на Прологе. older(X, Y) вызывает новый предикат older(X,Z), который в свою очередь вызывает следующий предикат older и так далее…

Нужно как-то остановить зацикливание. Если подумать, зачем нам проверять первый предикат «older(X, Z)» через правила? Если не нашел факт, то значит весь предикат older(X, Y) ложный (подумайте, почему).

Нужно объяснить Прологу, что факты и правила нужно проверять во второй части older(Z, Y), а в первой older(X, Y) — только факты

Нужно объяснить Прологу, что если он в первый раз не смог найти нужный факт, то ему не нужно приступать к правилу. Нам нужно как-то объяснить Прологу, где факт, а где правило.

Это задачу можно решить, добавив к предикатам ещё один аргумент, который будет показывать — это правило или факт.

% Это факты

older(sasha, lesha, fact). % Саша старше Лёши

older(misha, sasha, fact). % Миша старше Саши

older(misha, dasha, fact). % Миша старше Даши

older(masha, misha, fact). % Маша старше Миши

% Это правило

older(X,Y, rule) :- older(X, Z, fact), older(Z,Y, _).

% X старше Y, если X старше Z и Z старше Y

% Проще: X > Y, если X > Z и Z > Y

%

% X, Y, Z - это переменные.

% Пролог перебирает все возможные X, Y, Z.

% Вместо X, Y, Z подставляются misha, dasha, sasha, lesha

% Например: Миша старше Лёши, если Миша старше Саши и Саша старше ЛёшиНижнее подчеркивание «_» — это анонимная переменная. Её используют, когда нам не важно, какое значение будет на её месте. Нам важно, чтобы первая часть правила была фактом. А вторая часть может быть любой.

Запустим код.

?- older(masha, X, _).

X = misha ;

X = sasha ;

X = dasha ;

X = lesha ;

false.Наша программа вывела все верные ответы.

Возможно, возникает вопрос: откуда Пролог знает, что изучает Марк и что Миша старше Даши? Как он понимает такие человеческие понятия? Почему ассоциируется study(mark, math) с фразой «Марк изучает математику»? Почему не с «математика изучает Марка»?. Это наше представление. Мы договорились, что пусть первый терм будет обозначать «субъект», сам предикат «взаимосвязь», а второй терм «объект». Мы могли бы воспринимать по-другому. Это просто договеренность о том, как воспринимать предикаты. Пролог позволяет нам абстрактно описать взаимоотношения между термами.

Напишем предикат для нахождения факториала от N.

factorial(1, 1).

factorial(N, F):-

N1 is N-1,

factorial(N1, F1),

F is F1*N.

% В Прологе пробелы, табуляция и новые строки работают также, как C/C++.

% Главное в конце закончить предикат точкой.«is» означает присвоить, т.е N1 будет равняться N-1. Присвоение значений переменным Пролога называется унификацией. «is» работает только для чисел. Чтобы можно было присваивать атомы, нужно вместо «is» использовать «=».

Зададим запросы. Здесь стоит прожимать Enter, чтобы получить первое решение и не попасть в бесконечный цикл.

?- factorial(1,F).

F = 1 .

?- factorial(2,F).

F = 2 .

?- factorial(3,F).

F = 6 .

?- factorial(4,F).

F = 24 .

?- factorial(5,F).

F = 120 .

?- factorial(10,F).

F = 3628800 .Можно улучшить, добавив дополнительное условие, что N должно быть больше или равно 0. Тогда наше решение точно не попадет в бесконечный цикл.

factorial(1, 1).

factorial(N, F):-

N >= 0,

N1 is N-1,

factorial(N1, F1),

F is F1*N.В качестве упражнения я предлагаю вам решить такие задачи:

-

Описать свое генеалогическое древо на предикатах female(X), male(X) и parent(X,Y).

-

Написать предикат нахождения N числа ряда Фибоначчи.

-

Описать дерево (граф без циклов) и найти, с какими вершинами связанная заданная вершина.

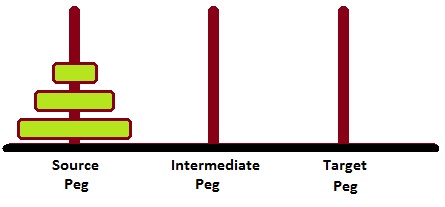

Списки в Prolog

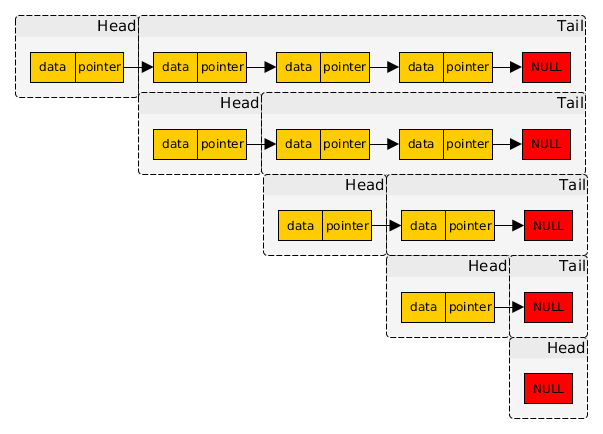

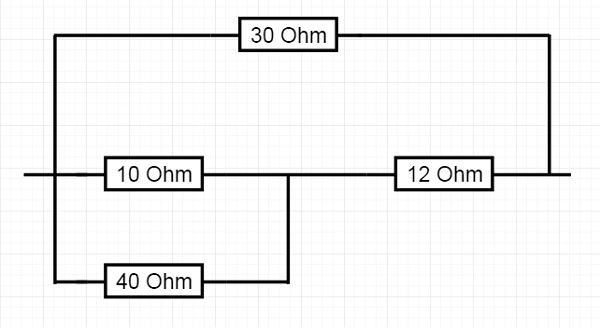

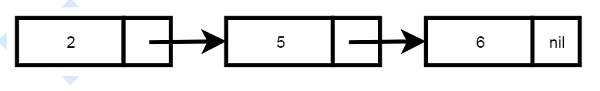

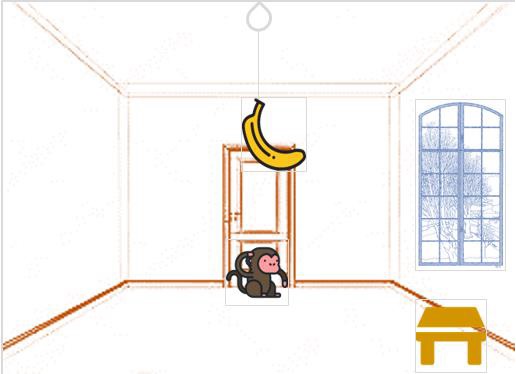

Списки — важная структура в Прологе. Списки позволяют хранить произвольное количество данных. Связный список — структура данных, состоящая из узлов. Узел содержит данные и ссылку (указатель, связку) на один или два соседних узла. Списки языка Prolog являются односвязными, т.е. каждый узел содержит лишь одну ссылку. Приложу наглядную картинку.

Кстати, ещё одна хорошая статья про списки в Прологе.

Списки в Прологе отличаются от списков в C/C++, Python и других процедурных языков. Здесь список — это либо пустой элемент; либо один элемент, называемый головой, и присоединенный список — хвост. Список — это рекурсивная структура данных с последовательным доступом.

Списки выглядят так: [],[a], [abc, bc], [‘Слово 1’, ‘Слово 2’, 1234], [X], [Head|Tail].

Рассмотрим [Head|Tail]. Это всё список, в котором мы выделяем первый элемент, голову списка, и остальную часть, хвост списка. Чтобы отделить первые элементы от остальной части списка, используется прямая черта «|».

Можно было написать такой список [X1,X2,X3|Tail]. Тогда мы выделим первые три элемента списка и положим их в X1, X2, X3, а остальная часть списка будет в Tail.

В списках хранятся данные, и нам нужно с ними работать. Например, находить минимум, максимум, медиану, среднее, дисперсию. Может нужно найти длину списка, длину самого длинного атома, получить средний балл по N предмету среди студентов группы G. Может нужно проверить, есть ли элемент Elem в списке List. И так далее. Короче, нужно как-то работать со списками. Только предикаты могут обрабатывать списки (да и в целом в Прологе все обрабатывается предикатами).

Напишем предикат для перебора элементов списка, чтобы понять принцип работы списка.

% element(Список, Элемент)

element([Head|Tail], Element) :- Element = Head; element(Tail, Element).

?- element([1,2,3,4,5,6, 'abc', 'prolog'], Elem).

Elem = 1 ;

Elem = 2 ;

Elem = 3 ;

Elem = 4 ;

Elem = 5 ;

Elem = 6 ;

Elem = abc ;

Elem = prolog ;

false.element([Head|Tail],Element) будет истинным, если Element равен Head (первому элементу списка) ИЛИ если предикат element(Tail, Element) истинный. В какой-то момент эта рекурсия окончится. (Вопрос читателю: когда кончится рекурсия? Какое условие будет терминирующим?) Таким образом, предикат будет истинным, если Element будет равен каждому элементу списка [Head|Tail]. Пролог найдет все решения, и мы переберем все элементы списка.

Часто бывает нужным знать длину списка. Напишем предикат для нахождения длины списка. Протестим.

% list_length(Список, Длина списка)

list_length([], 0).

list_length([H|T], L) :- list_length(T, L1), L is L1+1.

?- list_length([123446,232,2332,23], L).

L = 4.

?- list_length([123446,232,2332,23,sdfds,sdfsf,sdfa,asd], L).

L = 8.

?- list_length([], L).

L = 0.

?- list_length([1], L).

L = 1.

?- list_length([1,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2], L).

L = 9.

Мой Пролог предупреждает, что была не использована переменная H. Код будет работать, но лучше использовать анонимную переменную _, вместо singleton переменной.

В SWI Prolog имеется встроенный предикат length. Я реализовал аналогичный предикат list_length. Если встречается пустой список, то его длина равна нулю. Иначе отсекается голова списка, рекурсивно определяется длина нового получившегося списка и к результату прибавляется единица.

Чтобы лучше понять алгоритм, пропишите его на бумаге. Последовательно, так, как делает Пролог.

Последняя задача про списки в этой статье, это определить, принадлежит ли элемент списку. Например, 1, 2, 3 и 4 являются элементами списка [1,2,3,4]. Этот предикат мы назовем list_member.

mymember(Elem, [Elem|_]).

mymember(Elem, [_|Tail]) :- mymember(Elem, Tail).Очевидно, что если список начинается с искомого элемента, то элемент принадлежит списку. В противном случае необходимо отсечь голову списка и рекурсивно проверить наличие элемента в новом получившемся списке.

Преимущества и недостатки Prolog

Пролог удобен в решении задач, в которых мы знаем начальное состояние (объекты и отношения между ними) и в которых нам трудно задать четкий алгоритм поиска решений. То есть чтобы Пролог сам нашел ответ.

Список задач, в которых Пролог удобен:

-

Искусственный интеллект

-

Компьютерная лингвистика. Написание стихов, анализ речи

-

Поиск пути в графе. Работа с графами

-

Логические задачи

-

Нечисловое программирование

Знаменитую логическую задачу Эйнштейна можно гораздо легче решить на Прологе, чем на любом другом императивном языке. Одна из вариаций такой задачи:

Задача Эйнштейна

На улице стоят пять домов. Каждый из пяти домов окрашен в свой цвет, а их жители — разных национальностей, владеют разными животными, пьют разные напитки и имеют разные профессии.

-

Англичанин живёт в красном доме.

-

У испанца есть собака.

-

В зелёном доме пьют кофе.

-

Украинец пьёт чай.

-

Зелёный дом стоит сразу справа от белого дома.

-

Скульптор разводит улиток.

-

В жёлтом доме живет математик.

-

В центральном доме пьют молоко.

-

Норвежец живёт в первом доме.

-

Сосед поэта держит лису.

-

В доме по соседству с тем, в котором держат лошадь, живет математик.

-

Музыкант пьёт апельсиновый сок.

-

Японец программист.

-

Норвежец живёт рядом с синим домом.

Кто пьёт воду? Кто держит зебру?

Замечание: в утверждении 6 справа означает справа относительно вас.

Научиться решать логические задачи на Пролог, можно по этой статье.

Ещё одна интересная статья. В ней автор пишет программу сочинитель стихов на Prolog.

Интересная задача, которую вы можете решить на Прологе: раскрасить граф наименьшим количеством цветов так, чтобы смежные вершины были разного цвета.

Пролог такой замечательный язык! Но почему его крайне редко используют?

Я вижу две причины:

-

Производительность

-

Альтернативы (например, нейросетей на Python)

Пролог решает задачи методом полного перебора. Следовательно, его сложность растет как O(n!). Конечно, можно использовать отсечения, например, с помощью «!». Но все равно сложность останется факториальной. Простые задачи не так интересны, а сложные лучше реализовать жадным алгоритмом на императивном языке.

Области, для которых предназначен Пролог, могут также успешно решаться с помощью Python, C/C++, C#, Java, нейросетей. Например, сочинение стихов, анализ речи, поиск пути в графе и так далее.

Я не могу сказать, что логическое программирование не нужно. Оно действительно развивает логическое мышление. Элементы логического программирования можно встретить на практике. И в принципе, логическое программирование — интересная парадагима, которую полезно знать, например, специалистам ИИ.

Что дальше?

Я понимаю, что статью я написал суховато и слишком «логично» (вероятно, влияние Пролога). Я надеюсь, статья вам помогла в изучении основ Логического Программирования на примере Пролога.

(Мои мысли: я часто использую повторения в статье. Это не сочинение, это туториал. Лучше не плодить ненужные синонимы и чаще использовать термины. По крайней мере, в туториалах. Так лучше запоминается. Повторение — мать учения. А как вы считаете?).

Это моя дебютная статья, и я буду очень рад конструктивной критике. Задавайте вопросы, пишите комментарии, я постараюсь отвечать на них. В конце статьи я приведу все ссылки, которые я упоминал и которые мне показались полезными.

Статью написал Горохов Михаил, успехов в обучении и в работе!

Ссылки

-

Ссылка на скачивание SWI Prolog

-

Синтаксис Пролога и его терминология

-

Предикаты в Пролог

-

Списки в Пролог

-

Логические задачи

-

Сочинение стихов с помощью Пролог

-

И конечно же ссылка на Википедию

-

Слышали о Пролог?

-

Примеры использования Пролог

Содержание

Друзья! В связи с большим количеством писем по данному разделу, хочу сообщить, что в настоящее время (апрель 2020 года) планирую активно развивать раздел, посвящённый SWI–Prolog-у. Данный Prolog может показать кому-то не очень удобным в освоении и использовании, но это только на первый взгляд. Это достаточно мощная и активно развивающаяся реализация Prolog и к тому же — бесплатная. Конечно, это только моё мнение

Если вас интересуют другие реализации Prolog-а, то пишите об этом в комментариях или мне ok@verim.org

Буду думать и в этом направлении…

Пролог (Prolog) для начинающих, для «чайников», для Dummies — это руководство для начинающих, которые хотели бы изучить язык программирования Пролог (Prolog). В данном руководстве собран богатый теоретический и практический материал. Все статьи проиллюстрированы работающими программами на Пролог (Prolog). Большинство программ протестированы в среде SWI–Prolog, Turbo Prolog 2.0, а также в EZY Prolog. Описание синтаксиса дано для Turbo Prolog 2.0.

Реализации Пролога

-

Visual Prolog

-

C&M Prolog

-

EZY Prolog

Пример HTML-страницы

Учебный курс (уроки) Пролога

-

-

Ввод:

-

Вывод:

-

Учебный курс (уроки) Visual Prolog

Листинги программ на Прологе

-

Предикаты:

-

Предикаты нулевой арности:

-

Отрицание:

-

Составные объекты:

-

Программа «Библиотека-2» — использование трехуровневой доменной структуры и четырехуровневой предикатной.

-

Арифметические операции:

-

Повторение, рекурсия и откат:

-

Программа «Служащие» — метод отката после неудачи с предикатом fail. Программа: выводит полный список служащих; выводит список мужчин; расчитывает почасовую оплату.

-

Списки:

-

Программа «Списки» — работа со списками, вывод содержимого списка, вывод отдельных элементов списка.

-

компоновка данных в список с целью вычисления среднего значения с помощью предиката findall.

-

-

Ввод-вывод:

-

Программа «Ввод слова с клавиатуры» — ввод слова с клавиатуры — демонстрация метода повтора с помощью простой рекурсии repeat. Программа считывает строку введенную с клавиатуры, и дублирует ее на экран. Если пользователь введет stop, то программа завершается.

-

Что ещё почитать?

| Fundamental Prolog |

|---|

|

В этом руководстве по языку Prolog мы ознакомимся с фундаментальными идеями языка программирования Prolog.

Язык системы программирования Visual Prolog является объектно-ориентированным, строго типизированным и с контролируемым режимов предикатов.

Естественно, это все необходимо освоить для написания программ в системе Visual Prolog.

Однако, в этом руководстве мы сосредоточимся на ядре программных текстов, то есть на текстах Пролога безотносительно классов, типов и режимов.

С этой целью мы будем использовать пример приложения PIE (Prolog Inference Engine — Машина Вывода Пролога), который включен в комплект системы программирования Visual Prolog. PIE можно также сгрузить в виде исполняемого приложения с сайта.

PIE является «классическим» интерпретатором, используя который можно изучать и экспериментировать с Прологом безо всего, что касается классов, типов и т.д.

Логика Хороновских клаузов

Visual Prolog, как и другие диалекты языка Пролог, базируется на логике хороновских клаузов.

Логика Хорновских Клаузов является формальной системой для заключений относительно сущностей и для установления отношений между ними.

В естественном языка мы можем сформулировать предложение вроде:

John is the father of Bill. (Джон является отцом Билла)

Здесь мы имеем две сущности: Джон (John) и Билл (Bill). Кроме того мы здесь имеем отношение между ними, а именно то, что один является отцом другому.

В логике хорновских клаузов мы пожем формализовать это утверждение следующим образом:

father("Bill", "John"). или отец("Билл","Джон").

father (отец) является предикатом или отношением с двумя аргументами, где второй является отцом первого.

Заметьте что мы выбрали так, что именно второй человек является отцом первого.

Мы могли бы выбрать и другой способ, поскольку порядок аргументов является прерогативой разработчика формальной системы.

Однако, сделав однажды выбор, следует в дальнейшем его придерживаться.

Итак в нашей формализации отец всегда должен быть вторым.

I have chosen to represent the persons by their names (which are string literals).

In a more complex world this would not be sufficient because many people have same name.

But for now we will be content with this simple formalization.

With formalizations like the one above I can state any kind of family relation between any persons.

But for this to become really interesting I will also have to formalize rules like this:

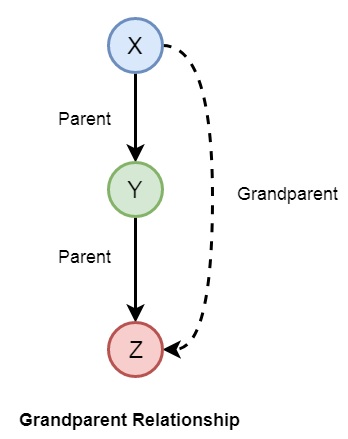

X is the grandfather of Z, if X is the father of Y and Y is the father of Z

where X, Y and Z are persons.

In Horn Clause Logic I can formalize this rule like this:

grandFather(Person, GrandFather) :- father(Person, Father), father(Father, GrandFather).

I have chosen to use variable names that help understanding better than X, Y and Z.

I have also introduced a predicate for the grandfather relation.

Again I have chosen that the grandfather should be the second argument.

It is wise to be consistent like that, i.e. that the arguments of the different predicates follow some common principle.

When reading rules you should interpret :- as if and the comma that separates the relations as and.

Statements like «John is the father of Bill» are called facts, while statements like «X is the grandfather of Z, if X is the father of Y and Y is the father of Z» are called rules.

With facts and rules we are ready to formulate theories.

A theory is a collection of facts and rules.

Let me state a little theory:

father("Bill", "John"). father("Pam", "Bill"). grandFather(Person, GrandFather) :- father(Person, Father), father(Father, GrandFather).

The purpose of the theory is to answer questions like these:

Is John the father of Sue? Who is the father of Pam? Is John the grandfather of Pam? ...

Such questions are called goals.

And they can be formalized like this (respectively):

?- father("Sue", "John"). ?- father("Pam", X). ?- grandFather("Pam", "John").

Such questions are called goal clauses or simply goals.

Together facts, rules and goals are called Horn clauses, hence the name Horn Clause Logic.

Some goals like the first and last are answered with a simple yes or no.

For other goals like the second we seek a solution, like X = «Bill».

Some goals may even have many solutions.

For example:

has two solutions:

X = "Bill", Y = "John". X = "Pam", Y = "Bill".

A Prolog program is a theory and a goal.

When the program starts it tries to find a solution to the goal in the theory.

PIE: Prolog Inference Engine

Now we will try the little example above in PIE, the Prolog Inference Engine that comes with Visual Prolog.

You can also download it from the web.

Before we start you should install and build the PIE example.

- Select «Install Examples» in the Windows start menu (Start -> Visual Prolog -> Install Examples).

- Open the PIE project in the VDE and run the program, as it is described in <a href=»../tut01/default.htm»>Tutorial 01: Environment Overview</a>.

When the program starts it will look like this:

Select File -> New and enter the father and grandFather clauses above:

While the editor window is active choose Engine -> Reconsult.

This will load the file into the engine.

In the Dialog window you should receive a message like this:

Reconsulted from: ....pieExeFILE4.PRO

Reconsult loads whatever is in the editor, without saving the contents to the file, if you want to save the contents use File -> Save.

File -> Consult will load the disc contents of the file regardless of whether the file is opened for editing or not.

Once you have «consulted» the theory, you can use it to answer goals.

On a blank line in the Dialog window type a goal (without the ?- in front).

For example:

When the caret is placed at the end of the line, press the Enter key on your keyboard.

PIE will now consider the text from the beginning of the line to the caret as a goal to execute.

You should see a result like this:

Extending the family theory

It is straight forward to extend the family theory above with predicates like mother and grandMother.

You should try that yourself.

You should also add more persons.

I suggest that you use persons from your own family, because that makes it lot easier to validate, whether some person is indeed the grandMother of some other person, etc.

Given mother and father we can also define a parent predicate.

You are a parent if you are a mother; you are also a parent if you are a father.

Therefore we can define parent using two clauses like this:

parent(Person, Parent) :- mother(Person, Parent). parent(Person, Parent) :- father(Person, Parent).

The first rule reads (recall that the second argument corresponds to the predicate name):

Parent is the parent of Person, if Parent is the mother of Person

You can also define the parent relation using semicolon «;» which means or, like this:

parent(Person, Parent) :- mother(Person, Parent); father(Person, Parent).

This rule reads:

Parent is the parent of Person, if Parent is the mother of Person or Parent is the father of Person

I will however advise you to use semicolon as little as possible (or actually not at all).

There are several reasons for this:

- The typographical difference «,» and «;» is very small, but the semantic difference is rather big. «;» is often a source of confusion, since it is easily misinterpreted as «,», especially when it is on the end of a long line.

- Visual Prolog only allows to use semicolon on the outermost level (PIE will allow arbitrarily deep nesting).

Try creating a sibling predicate! Did that give problems?

You might find that siblings are found twice.

At least if you say: Two persons are siblings if they have same mother, two persons are also siblings if they have same father.

I.e. if you have rules like this:

sibling(Person, Sibling) :- mother(Person, Mother), mother(Sibling, Mother). sibling(Person, Sibling) :- father(Person, Father), father(Sibling, Father).

The first rule reads:

Sibling is the sibling of Person, if Mother is the mother of Person and Mother is the mother of Sibling

The reason that you receive siblings twice is that most siblings both have same father and mother, and therefore they fulfill both requirements above.

And therefore they are found twice.

We shall not deal with this problem now; currently we will just accept that some rules give too many results.

A fullBlodedSibling predicate does not have the same problem, because it will require that both the father and the mother are the same:

fullBlodedSibling(Person, Sibling) :- mother(Person, Mother), mother(Sibling, Mother), father(Person, Father), father(Sibling, Father).

Prolog is a Programming Language

From the description so far you might think that Prolog is an expert system, rather than a programming language.

And indeed Prolog can be used as an expert system, but it is designed to be a programming language.

We miss two important ingredients to turn Horn Clause logic into a programming language:

- Rigid search order/program control

- Side effects

Program Control

When you try to find a solution to a goal like:

You can do it in many ways.

For example, you might just consider at the second fact in the theory and then you have a solution.

But Prolog does not use a «random» search strategy, instead it always use the same strategy.

The system maintains a current goal, which is always solved from left to right.

I.e. if the current goal is:

?- grandFather(X, Y), mother(Y, Z).

Then the system will always try to solve the sub-goal grandFather(X, Y) before it solves mother(Y, Z), if the first (i.e. left-most) sub-goal cannot be solved then there is no solution to the overall problem and then the second sub-goal is not tried at all.

When solving a particular sub-goal, the facts and rules are always tried from top to bottom.

When a sub-goal is solved by using a rule, the right hand side replaces the sub-goal in the current goal.

I.e. if the current goal is:

?- grandFather(X, Y), mother(Y, Z).

And we are using the rule

grandFather(Person, GrandFather) :- father(Person, Father), father(Father, GrandFather).

to solve the first sub-goal, then the resulting current goal will be:

?- father(X, Father), father(Father, Y), mother(Y, Z).

Notice that some variables in the rule have been replaced by variables from the sub-goal.

I will explain this in details later.

Given this evaluation strategy you can interpret clauses much more procedural. Consider this rule:

grandFather(Person, GrandFather) :- father(Person, Father), father(Father, GrandFather).

Given the strict evaluation we can read this rule like this:

To solve grandFather(Person, GrandFather) first solve father(Person, Father) and then solve father(Father, GrandFather).

Or even like this:

When grandFather(Person, GrandFather) is called, first call father(Person, Father) and then call father(Father, GrandFather).

With this procedural reading you can see that predicates correspond to procedures/subroutines in other languages.

The main difference is that a Prolog predicate can return several solutions to a single invocation or even fail.

This will be discussed in details in the next sections.

Failing

A predicate invocation might not have any solution in the theory.

For example calling parent(«Hans», X) has no solution as there are no parent facts or rules that applies to «Hans».

We say that the predicate call fails.

If the goal fails then there is simply no solution to the goal in the theory.

The next section will explain how failing is treated in the general case, i.e. when it is not the goal that fails.

Backtracking

In the procedural interpretation of a Prolog program «or» is treated in a rather special way.

Consider the clause

parent(Person, Parent) :- mother(Person, Parent); father(Person, Parent).

In the logical reading we interpreted this clause as:

Parent

is the parent of Person if

Parent is the mother of

Person or

Parent is the father of Person.

The «or» introduces two possible solutions to an invocation of the parent predicate.

Prolog handles such multiple choices by first trying one choice and later (if necessary) backtracking to the next alternative choice, etc.

During the execution of a program a lot of alternative choices (known as backtrack points) might exist from earlier predicate calls.

If some predicate call fails, then we will backtrack to the last backtrack point we met and try the alternative solution instead.

If no further backtrack points exists then the overall goal has failed, meaning that there was no solution to it.

With this in mind we can interpret the clause above like this:

When parent(Person, Parent) is called first record a backtrack point to the second alternative solution (i.e. to the call to father(Person, Parent)) and then call mother(Person, Parent)

A predicate that has several classes behave in a similar fashion.

Consider the clauses:

father("Bill", "John"). father("Pam", "Bill").

When father is invoked we first record a backtrack point to the second clause, and then try the first clause.

If there are three or more choices we still only create one backtrack point, but that backtrack point will start by creating another backtrack point.

Consider the clauses:

father("Bill", "John"). father("Pam", "Bill"). father("Jack", "Bill").

When father is invoked, we first record a backtrack point.

And then we try the first clause.

The backtrack point we create points to some code, which will itself create a backtrack point (namely to the third clause) and then try the second clause.

Thus all choice points have only two choices, but one choice might itself involve a choice.

Example To illustrate how programs are executed I will go through an example in details.

Consider these clauses:

mother("Bill", "Lisa"). father("Bill", "John"). father("Pam", "Bill"). father("Jack", "Bill"). parent(Person, Parent) :- mother(Person, Parent); father(Person, Parent).

And then consider this goal:

?- father(AA, BB), parent(BB, CC).

This goal states that we want to find three persons AA, BB and CC, such that BB is the father of AA and CC is a parent of BB.

As mentioned we always solve the goals from left to right, so first we call the father predicate.

When executing the father predicate we first create a backtrack point to the second clause, and then use the first clause.

Using the first clause we find that AA is «Bill» and BB is «John».

So we now effectively have the goal:

So we call parent, which gives the following goal:

?- mother("John", CC); father("John", CC).

You will notice that the variables in the clause have been replaced with the actual parameters of the call (exactly like when you call subroutines in other languages).

The current goal is an «or» goal, so we create a backtrack point to the second alternative and pursuit the first.

We now have two active backtrack points, one to the second alternative in the parent clause, and one to the second clause in the father predicate.

After the creation of this backtrack point we are left with the following goal:

So we call the mother predicate.

The mother predicate fails when the first argument is «John» (because it has no clauses that match this value in the first argument).

In case of failure we backtrack to the last backtrack point we created.

So we will now pursuit the goal:

When calling father this time, we will again first create a backtrack point to the second father clause.

Recall that we also still have a backtrack point to the second clause of the father predicate, which corresponds to the first call in the original goal.

We now try to use the first father clause on the goal, but that fails, because the first arguments do not match (i.e. «John» does not match «Bill»).

Therefore we backtrack to the second clause, but before we use this clause we create a backtrack point to the third clause.

The second clause also fails, since «John» does not match «Pam», so we backtrack to the third clause.

This also fails, since «John» does not match «Jack».

Now we must backtrack all the way back to the first father call in the original goal; here we created a backtrack point to the second father clause.

Using the second clause we find that AA is «Pam» and BB is «Bill».

So we now effectively have the goal:

When calling parent we now get:

?- mother("Bill", CC); father("Bill", CC).

Again we create a backtrack point to the second alternative and pursuit the first:

This goal succeeds with CC being «Lisa».

So now we have found a solution to the goal:

AA = "Pam", BB = "Bill", CC = "Lisa".

When trying to find additional solutions we backtrack to the last backtrack point, which was the second alternative in the parent predicate:

This goal will also succeed with CC being «John».

So now we have found one more solution to the goal:

AA = "Pam", BB = "Bill", CC = "John".

If we try to find more solutions we will find:

AA = "Jack", BB = "Bill", CC = "John". AA = "Jack", BB = "Bill", CC = "Lisa".

After that we will experience that everything will eventually fail leaving no more backtrack points.

So all in all there are four solutions to the goal.

Improving the Family Theory

If you continue to work with the family relation above, you will probably find out that you have problems with relations like brother and sister, because it is rather difficult to determine the sex of a person (unless the person is a father or mother).

The problem is that we have chosen a bad way to formalize our theory.

The reason that we arrived at this theory is because we started by considering the relations between the entities.

If we instead first focus on the entities, then the result will naturally become different.

Our main entities are persons.

Persons have a name (in this simple context will still assume that the name identifies the person, in a real scale program this would not be true).

Persons also have a sex.

Persons have many other properties, but none of them have any interest in our context.

Therefore we define a person predicate, like this:

person("Bill", "male"). person("John", "male"). person("Pam", "female").

The first argument of the person predicate is the name and the second is the sex.

Instead of using mother and father as facts, I will choose to have parent as facts and mother and father as rules:

parent("Bill", "John"). parent("Pam", "Bill"). father(Person, Father) :- parent(Person, Father), person(Father, "male").

Notice that when father is a «derived» relation like this, it is impossible to state female fathers.

So this theory also has a built-in consistency on this point, which did not exist in the other formulation.

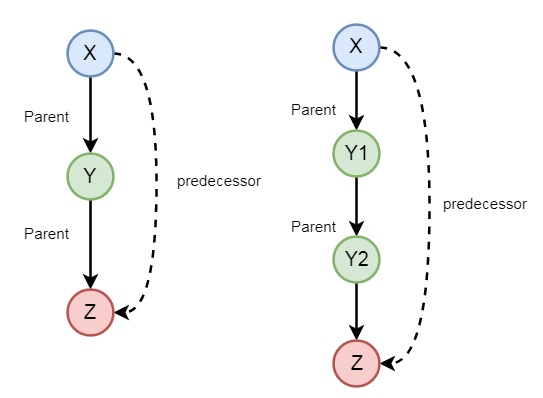

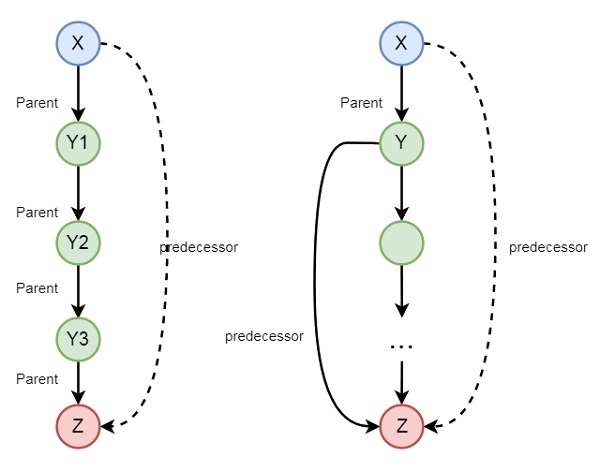

Recursion

Most family relations are easy to construct given the principles above.

But when it comes to «infinite» relations like ancestor we need something more.

If we follow the principle above, we should define ancestor like this:

ancestor(Person, Ancestor) :- parent(Person, Ancestor). ancestor(Person, Ancestor) :- parent(Person, P1), parent(P1, Ancestor). ancestor(Person, Ancestor) :- parent(Person, P1), parent(P1, P2), parent(P2, Ancestor). ...

The main problem is that this line of clauses never ends.

The way to overcome this problem is to use a recursive definition, i.e. a definition that is defined in terms of itself. like this:

ancestor(Person, Ancestor) :- parent(Person, Ancestor). ancestor(Person, Ancestor) :- parent(Person, P1), ancestor(P1, Ancestor).

This declaration states that a parent is an ancestor, and that an ancestor to a parent is also an ancestor.

If you are not already familiar with recursion you might find it tricky (in several senses).

Recursion is however fundamental to Prolog programming.

You will use it again and again, so eventually you will find it completely natural.

Let us try to execute an ancestor goal:

We create a backtrack point to the second ancestor clause, and then we use the first, finding the new goal:

This succeeds with the solution:

Then we try to find another solution by using our backtrack point to the second ancestor clause.

This gives the new

goal:

?- parent("Pam", P1), ancestor(P1, AA).

Again «Bill» is the

parent of «Pam»,

so we find P1=

«Bill», and then we have the goal:

To solve this goal we first create a backtrack point to the second ancestor clause and then we use the first one.

This gives the following goal:

This goal has the gives the solution:

So now we have found two ancestors of «Pam»:

- «Bill» and

- «John».

If we use the backtrack point to the second ancestor clause we get the following goal:

?- parent("Bill", P1), ancestor(P1, AA).

Here we will again find that

«John» is the parent of

«Bill», and thus that

P1 is

«John».

This gives the goal:

If you pursuit this goal you will find that it will not have any solution.

So all in all we can only find two ancestors of

«Pam».

Recursion is very powerful but it can also be a bit hard to control.

Two things are important to remember:

- the recursion must make progress

- the recursion must terminate

In the code above the first clause ensures that the recursion can terminate, because this clause is not recursive (i.e. it makes no calls to the predicate itself).

In the second clause (which is recursive) we have made sure, that we go one ancestor-step further back, before making the recursive call.

I.e. we have ensured that we make some progress in the problem.

Side Effects

Besides a strict evaluation order Prolog also has side effects.

For example Prolog has a number of predefined predicates for reading and writing.

The following goal will write the found ancestors of «Pam»:

?- ancestor("Pam", AA), write("Ancestor of Pam : ", AA), nl().

The ancestor call will find an ancestor of «Pam» in AA.

The write call will write the string literal «Ancestor of Pam : «, and then it will write the value of AA.

The nl call will shift to a new line in the output.

When running programs in PIE, PIE itself writes solutions, so the overall effect is that your output and PIE’s own output will be mixed.

This might of course not be desirable.

A very simple way to avoid PIE’s own output is to make sure that the goal has no solutions.

Consider the following goal:

?- ancestor("Pam", AA), write("Ancestor of Pam : ", AA), nl(), fail.

fail is a predefined call that always fails (i.e. it has no solutions).

The first three predicate calls have exactly the same effect as above: an ancestor is found (if such one exists, of course) and then it is written.

But then we call fail this will of course fail. Therefore we must pursuit a backtrack point if we have any.

When pursuing this backtrack point, we will find another ancestor (if such one exists) and write that, and then we will fail again.

And so forth.

So, we will find and write all ancestors. and eventually there will be no more backtrack points, and then the complete goal will fail.

There are a few important points to notice here:

- The goal itself did not have a single solution, but nevertheless all the solutions we wanted was given as side effects.

- Side effects in failing computations are not undone.

These points are two sides of the same thing.

But they represent different level of optimism.

The first optimistically states some possibilities that you can use, while the second is more pessimistic and states that you should be aware about using side effects, because they are not undone even if the current goal does not lead to any solution.

Anybody, who learns Prolog, will sooner or later experience unexpected output coming from failing parts of the program.

Perhaps, this little advice can help you: Separate the «calculating» code from the code that performs input/output.

In our examples above all the stated predicate are «calculating» predicates.

They all calculate some family relation.

If you need to write out, for example, «parents», create a separate predicate for writing parents and let that predicate call the «calculating» parent predicate.

Conclusion

In this tutorial we have looked at some of the basic features of Prolog.

You have seen facts, rules and goals.

You learned about the execution strategy for Prolog including the notion of failing and backtracking.

You have also seen that backtracking can give many results to a single question.

And finally you have been introduced to side effects.

See also

- Основы Пролога. Часть 2

Ссылки

Prolog — Introduction

Prolog as the name itself suggests, is the short form of LOGical PROgramming. It is a logical and declarative programming language. Before diving deep into the concepts of Prolog, let us first understand what exactly logical programming is.

Logic Programming is one of the Computer Programming Paradigm, in which the program statements express the facts and rules about different problems within a system of formal logic. Here, the rules are written in the form of logical clauses, where head and body are present. For example, H is head and B1, B2, B3 are the elements of the body. Now if we state that “H is true, when B1, B2, B3 all are true”, this is a rule. On the other hand, facts are like the rules, but without any body. So, an example of fact is “H is true”.

Some logic programming languages like Datalog or ASP (Answer Set Programming) are known as purely declarative languages. These languages allow statements about what the program should accomplish. There is no such step-by-step instruction on how to perform the task. However, other languages like Prolog, have declarative and also imperative properties. This may also include procedural statements like “To solve the problem H, perform B1, B2 and B3”.

Some logic programming languages are given below −

-

ALF (algebraic logic functional programming language).

-

ASP (Answer Set Programming)

-

CycL

-

Datalog

-

FuzzyCLIPS

-

Janus

-

Parlog

-

Prolog

-

Prolog++

-

ROOP

Logic and Functional Programming

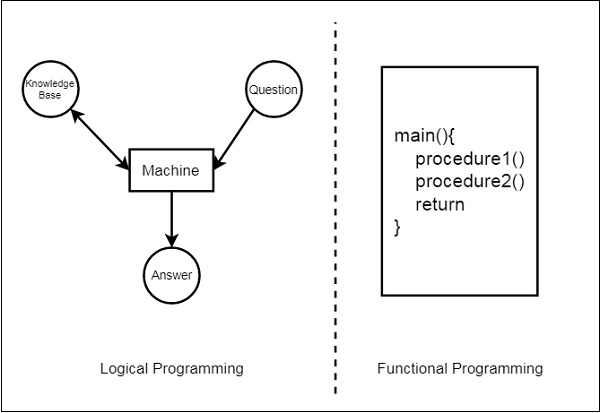

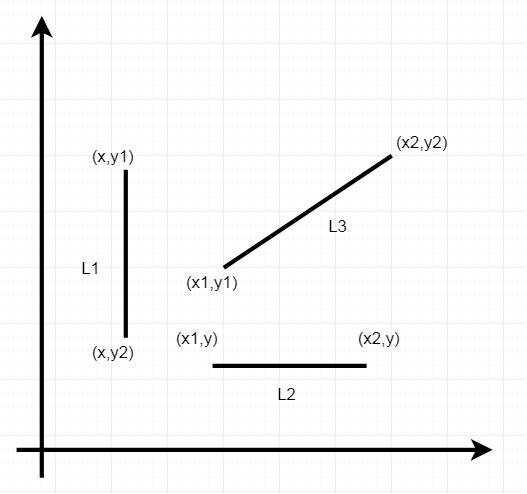

We will discuss about the differences between Logic programming and the traditional functional programming languages. We can illustrate these two using the below diagram −

From this illustration, we can see that in Functional Programming, we have to define the procedures, and the rule how the procedures work. These procedures work step by step to solve one specific problem based on the algorithm. On the other hand, for the Logic Programming, we will provide knowledge base. Using this knowledge base, the machine can find answers to the given questions, which is totally different from functional programming.

In functional programming, we have to mention how one problem can be solved, but in logic programming we have to specify for which problem we actually want the solution. Then the logic programming automatically finds a suitable solution that will help us solve that specific problem.

Now let us see some more differences below −

| Functional Programming | Logic Programming |

|---|---|

| Functional Programming follows the Von-Neumann Architecture, or uses the sequential steps. | Logic Programming uses abstract model, or deals with objects and their relationships. |

| The syntax is actually the sequence of statements like (a, s, I). | The syntax is basically the logic formulae (Horn Clauses). |

| The computation takes part by executing the statements sequentially. | It computes by deducting the clauses. |

| Logic and controls are mixed together. | Logics and controls can be separated. |

What is Prolog?

Prolog or PROgramming in LOGics is a logical and declarative programming language. It is one major example of the fourth generation language that supports the declarative programming paradigm. This is particularly suitable for programs that involve symbolic or non-numeric computation. This is the main reason to use Prolog as the programming language in Artificial Intelligence, where symbol manipulation and inference manipulation are the fundamental tasks.

In Prolog, we need not mention the way how one problem can be solved, we just need to mention what the problem is, so that Prolog automatically solves it. However, in Prolog we are supposed to give clues as the solution method.

Prolog language basically has three different elements −

Facts − The fact is predicate that is true, for example, if we say, “Tom is the son of Jack”, then this is a fact.

Rules − Rules are extinctions of facts that contain conditional clauses. To satisfy a rule these conditions should be met. For example, if we define a rule as −

grandfather(X, Y) :- father(X, Z), parent(Z, Y)

This implies that for X to be the grandfather of Y, Z should be a parent of Y and X should be father of Z.

Questions − And to run a prolog program, we need some questions, and those questions can be answered by the given facts and rules.

History of Prolog

The heritage of prolog includes the research on theorem provers and some other automated deduction system that were developed in 1960s and 1970s. The Inference mechanism of the Prolog is based on Robinson’s Resolution Principle, that was proposed in 1965, and Answer extracting mechanism by Green (1968). These ideas came together forcefully with the advent of linear resolution procedures.

The explicit goal-directed linear resolution procedures, gave impetus to the development of a general purpose logic programming system. The first Prolog was the Marseille Prolog based on the work by Colmerauer in the year 1970. The manual of this Marseille Prolog interpreter (Roussel, 1975) was the first detailed description of the Prolog language.

Prolog is also considered as a fourth generation programming language supporting the declarative programming paradigm. The well-known Japanese Fifth-Generation Computer Project, that was announced in 1981, adopted Prolog as a development language, and thereby grabbed considerable attention on the language and its capabilities.

Some Applications of Prolog

Prolog is used in various domains. It plays a vital role in automation system. Following are some other important fields where Prolog is used −

-

Intelligent Database Retrieval

-

Natural Language Understanding

-

Specification Language

-

Machine Learning

-

Robot Planning

-

Automation System

-

Problem Solving

Prolog — Environment Setup

In this chapter, we will discuss how to install Prolog in our system.

Prolog Version

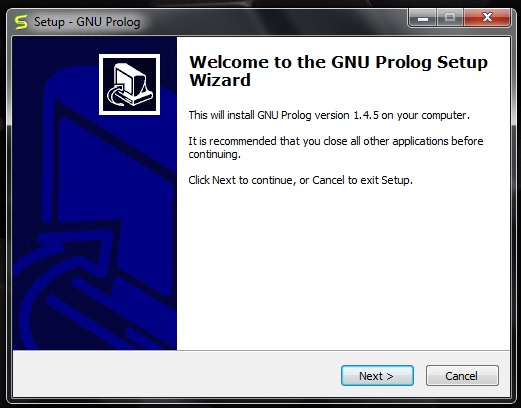

In this tutorial, we are using GNU Prolog, Version: 1.4.5

Official Website

This is the official GNU Prolog website where we can see all the necessary details about GNU Prolog, and also get the download link.

http://www.gprolog.org/

Direct Download Link

Given below are the direct download links of GNU Prolog for Windows. For other operating systems like Mac or Linux, you can get the download links by visiting the official website (Link is given above) −

http://www.gprolog.org/setup-gprolog-1.4.5-mingw-x86.exe (32 Bit System)

http://www.gprolog.org/setup-gprolog-1.4.5-mingw-x64.exe(64 Bit System)

Installation Guide

-

Download the exe file and run it.

-

You will see the window as shown below, then click on next −

Select proper directory where you want to install the software, otherwise let it be installed on the default directory. Then click on next.

You will get the below screen, simply go to next.

You can verify the below screen, and check/uncheck appropriate boxes, otherwise you can leave it as default. Then click on next.

In the next step, you will see the below screen, then click on Install.

Then wait for the installation process to finish.

Finally click on Finish to start GNU Prolog.

The GNU prolog is installed successfully as shown below −

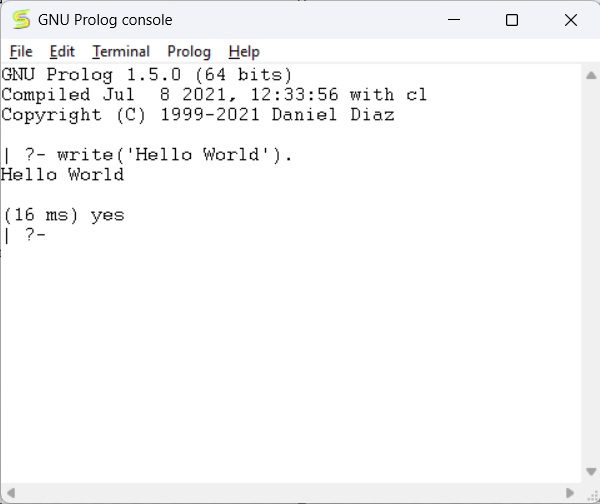

Prolog — Hello World

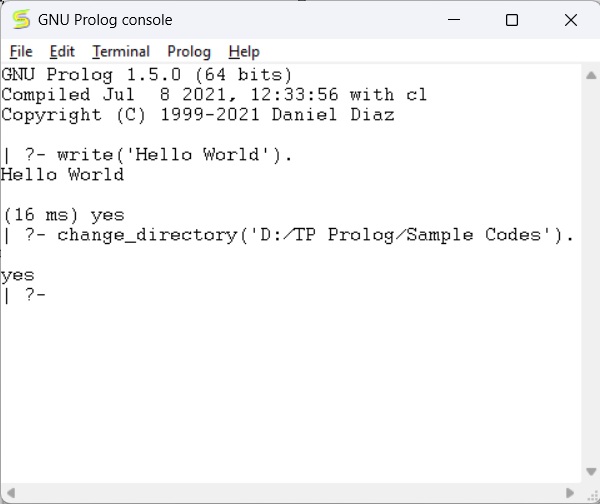

In the previous section, we have seen how to install GNU Prolog. Now, we will see how to write a simple Hello World program in our Prolog environment.

Hello World Program

After running the GNU prolog, we can write hello world program directly from the console. To do so, we have to write the command as follows −

write('Hello World').

Note − After each line, you have to use one period (.) symbol to show that the line has ended.

The corresponding output will be as shown below −

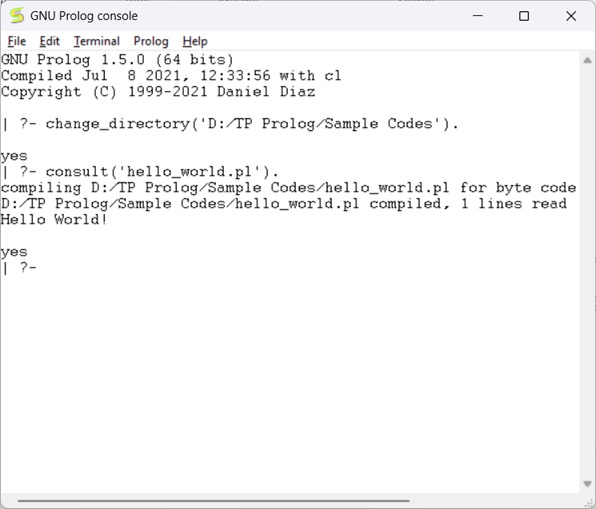

Now let us see how to run the Prolog script file (extension is *.pl) into the Prolog console.

Before running *.pl file, we must store the file into the directory where the GNU prolog console is pointing, otherwise just change the directory by the following steps −

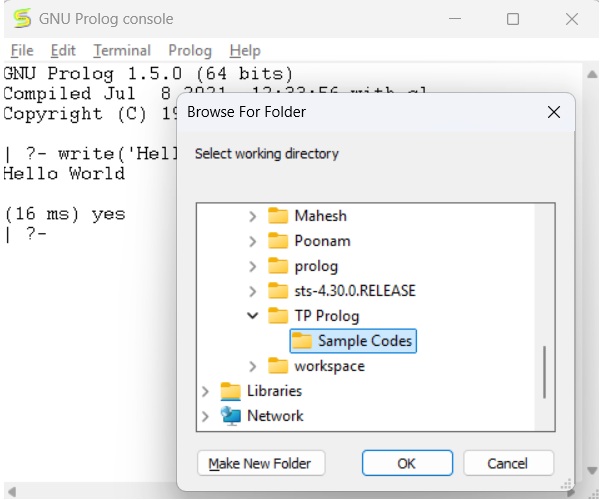

Step 1 − From the prolog console, go to File > Change Dir, then click on that menu.

Step 2 − Select the proper folder and press OK.

Now we can see in the prolog console, it shows that we have successfully changed the directory.

Step 3 − Now create one file (extension is *.pl) and write the code as follows −

main :- write('This is sample Prolog program'),

write(' This program is written into hello_world.pl file').

Now let’s run the code. To run it, we have to write the file name as follows −

[hello_world]

The output is as follows −

Prolog — Basics

In this chapter, we will gain some basic knowledge about Prolog. So we will move on to the first step of our Prolog Programming.

The different topics that will be covered in this chapter are −

Knowledge Base − This is one of the fundamental parts of Logic Programming. We will see in detail about the Knowledge Base, and how it helps in logic programming.

Facts, Rules and Queries − These are the building blocks of logic programming. We will get some detailed knowledge about facts and rules, and also see some kind of queries that will be used in logic programming.

Here, we will discuss about the essential building blocks of logic programming. These building blocks are Facts, Rules and the Queries.

Facts

We can define fact as an explicit relationship between objects, and properties these objects might have. So facts are unconditionally true in nature. Suppose we have some facts as given below −

-

Tom is a cat

-

Kunal loves to eat Pasta

-

Hair is black

-

Nawaz loves to play games

-

Pratyusha is lazy.

So these are some facts, that are unconditionally true. These are actually statements, that we have to consider as true.

Following are some guidelines to write facts −

-

Names of properties/relationships begin with lower case letters.

-

The relationship name appears as the first term.

-

Objects appear as comma-separated arguments within parentheses.

-

A period «.» must end a fact.

-

Objects also begin with lower case letters. They also can begin with digits (like 1234), and can be strings of characters enclosed in quotes e.g. color(penink, ‘red’).

-

phoneno(agnibha, 1122334455). is also called a predicate or clause.

Syntax

The syntax for facts is as follows −

relation(object1,object2...).

Example

Following is an example of the above concept −

cat(tom). loves_to_eat(kunal,pasta). of_color(hair,black). loves_to_play_games(nawaz). lazy(pratyusha).

Rules

We can define rule as an implicit relationship between objects. So facts are conditionally true. So when one associated condition is true, then the predicate is also true. Suppose we have some rules as given below −

-

Lili is happy if she dances.

-

Tom is hungry if he is searching for food.

-

Jack and Bili are friends if both of them love to play cricket.

-

will go to play if school is closed, and he is free.

So these are some rules that are conditionally true, so when the right hand side is true, then the left hand side is also true.

Here the symbol ( :- ) will be pronounced as “If”, or “is implied by”. This is also known as neck symbol, the LHS of this symbol is called the Head, and right hand side is called Body. Here we can use comma (,) which is known as conjunction, and we can also use semicolon, that is known as disjunction.

Syntax

rule_name(object1, object2, ...) :- fact/rule(object1, object2, ...) Suppose a clause is like : P :- Q;R. This can also be written as P :- Q. P :- R. If one clause is like : P :- Q,R;S,T,U. Is understood as P :- (Q,R);(S,T,U). Or can also be written as: P :- Q,R. P :- S,T,U.

Example

happy(lili) :- dances(lili). hungry(tom) :- search_for_food(tom). friends(jack, bili) :- lovesCricket(jack), lovesCricket(bili). goToPlay(ryan) :- isClosed(school), free(ryan).

Queries

Queries are some questions on the relationships between objects and object properties. So question can be anything, as given below −

-

Is tom a cat?

-

Does Kunal love to eat pasta?

-

Is Lili happy?

-

Will Ryan go to play?

So according to these queries, Logic programming language can find the answer and return them.

Knowledge Base in Logic Programming

In this section, we will see what knowledge base in logic programming is.

Well, as we know there are three main components in logic programming − Facts, Rules and Queries. Among these three if we collect the facts and rules as a whole then that forms a Knowledge Base. So we can say that the knowledge base is a collection of facts and rules.

Now, we will see how to write some knowledge bases. Suppose we have our very first knowledge base called KB1. Here in the KB1, we have some facts. The facts are used to state things, that are unconditionally true of the domain of interest.

Knowledge Base 1

Suppose we have some knowledge, that Priya, Tiyasha, and Jaya are three girls, among them, Priya can cook. Let’s try to write these facts in a more generic way as shown below −

girl(priya). girl(tiyasha). girl(jaya). can_cook(priya).

Note − Here we have written the name in lowercase letters, because in Prolog, a string starting with uppercase letter indicates a variable.

Now we can use this knowledge base by posing some queries. “Is priya a girl?”, it will reply “yes”, “is jamini a girl?” then it will answer “No”, because it does not know who jamini is. Our next question is “Can Priya cook?”, it will say “yes”, but if we ask the same question for Jaya, it will say “No”.

Output

GNU Prolog 1.4.5 (64 bits)

Compiled Jul 14 2018, 13:19:42 with x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc

By Daniel Diaz

Copyright (C) 1999-2018 Daniel Diaz

| ?- change_directory('D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes').

yes

| ?- [kb1]

.

compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb1.pl for byte code...

D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb1.pl compiled, 3 lines read - 489 bytes written, 10 ms

yes

| ?- girl(priya)

.

yes

| ?- girl(jamini).

no

| ?- can_cook(priya).

yes

| ?- can_cook(jaya).

no

| ?-

Let us see another knowledge base, where we have some rules. Rules contain some information that are conditionally true about the domain of interest. Suppose our knowledge base is as follows −

sing_a_song(ananya). listens_to_music(rohit). listens_to_music(ananya) :- sing_a_song(ananya). happy(ananya) :- sing_a_song(ananya). happy(rohit) :- listens_to_music(rohit). playes_guitar(rohit) :- listens_to_music(rohit).

So there are some facts and rules given above. The first two are facts, but the rest are rules. As we know that Ananya sings a song, this implies she also listens to music. So if we ask “Does Ananya listen to music?”, the answer will be true. Similarly, “is Rohit happy?”, this will also be true because he listens to music. But if our question is “does Ananya play guitar?”, then according to the knowledge base, it will say “No”. So these are some examples of queries based on this Knowledge base.

Output

| ?- [kb2]. compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb2.pl for byte code... D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb2.pl compiled, 6 lines read - 1066 bytes written, 15 ms yes | ?- happy(rohit). yes | ?- sing_a_song(rohit). no | ?- sing_a_song(ananya). yes | ?- playes_guitar(rohit). yes | ?- playes_guitar(ananya). no | ?- listens_to_music(ananya). yes | ?-

Knowledge Base 3

The facts and rules of Knowledge Base 3 are as follows −

can_cook(priya). can_cook(jaya). can_cook(tiyasha). likes(priya,jaya) :- can_cook(jaya). likes(priya,tiyasha) :- can_cook(tiyasha).

Suppose we want to see the members who can cook, we can use one variable in our query. The variables should start with uppercase letters. In the result, it will show one by one. If we press enter, then it will come out, otherwise if we press semicolon (;), then it will show the next result.

Let us see one practical demonstration output to understand how it works.

Output

| ?- [kb3].

compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb3.pl for byte code...

D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb3.pl compiled, 5 lines read - 737 bytes written, 22 ms

warning: D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb3.pl:1: redefining procedure can_cook/1

D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/kb1.pl:4: previous definition

yes

| ?- can_cook(X).

X = priya ? ;

X = jaya ? ;

X = tiyasha

yes

| ?- likes(priya,X).

X = jaya ? ;

X = tiyasha

yes

| ?-

Prolog — Relations

Relationship is one of the main features that we have to properly mention in Prolog. These relationships can be expressed as facts and rules. After that we will see about the family relationships, how we can express family based relationships in Prolog, and also see the recursive relationships of the family.

We will create the knowledge base by creating facts and rules, and play query on them.

Relations in Prolog

In Prolog programs, it specifies relationship between objects and properties of the objects.

Suppose, there’s a statement, “Amit has a bike”, then we are actually declaring the ownership relationship between two objects — one is Amit and the other is bike.

If we ask a question, “Does Amit own a bike?”, we are actually trying to find out about one relationship.

There are various kinds of relationships, of which some can be rules as well. A rule can find out about a relationship even if the relationship is not defined explicitly as a fact.

We can define a brother relationship as follows −

Two person are brothers, if,

-

They both are male.

-

They have the same parent.

Now consider we have the below phrases −

-

parent(sudip, piyus).

-

parent(sudip, raj).

-

male(piyus).

-

male(raj).

-

brother(X,Y) :- parent(Z,X), parent(Z,Y),male(X), male(Y)

These clauses can give us the answer that piyus and raj are brothers, but we will get three pairs of output here. They are: (piyus, piyus), (piyus, raj), (raj, raj). For these pairs, given conditions are true, but for the pairs (piyus, piyus), (raj, raj), they are not actually brothers, they are the same persons. So we have to create the clauses properly to form a relationship.

The revised relationship can be as follows −

A and B are brothers if −

-

A and B, both are male

-

They have same father

-

They have same mother

-

A and B are not same

Family Relationship in Prolog

Here we will see the family relationship. This is an example of complex relationship that can be formed using Prolog. We want to make a family tree, and that will be mapped into facts and rules, then we can run some queries on them.

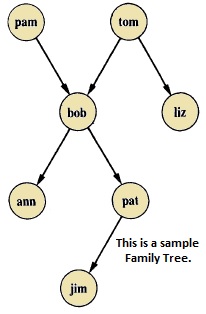

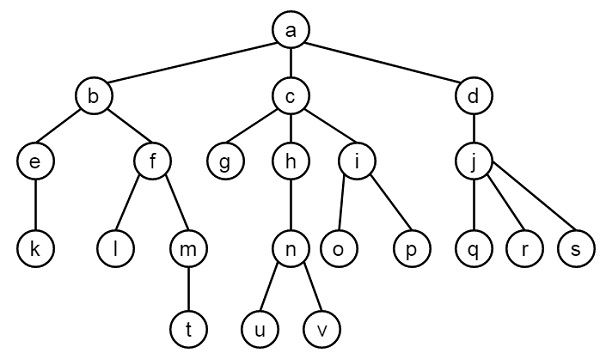

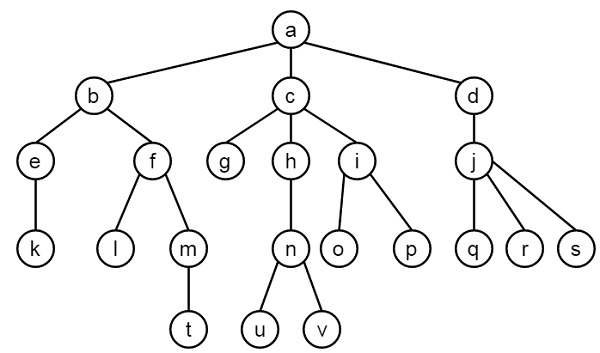

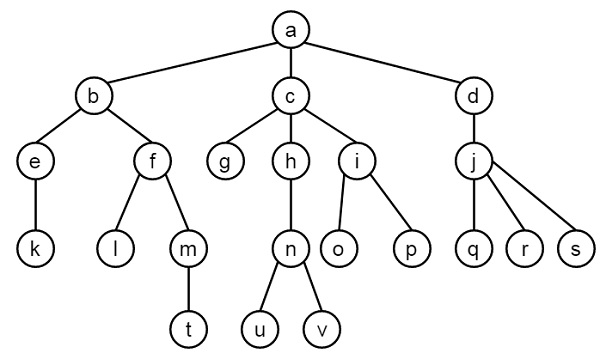

Suppose the family tree is as follows −

Here from this tree, we can understand that there are few relationships. Here bob is a child of pam and tom, and bob also has two children — ann and pat. Bob has one brother liz, whose parent is also tom. So we want to make predicates as follows −

Predicates

-

parent(pam, bob).

-

parent(tom, bob).

-

parent(tom, liz).

-

parent(bob, ann).

-

parent(bob, pat).

-

parent(pat, jim).

-

parent(bob, peter).

-

parent(peter, jim).

From our example, it has helped to illustrate some important points −

-

We have defined parent relation by stating the n-tuples of objects based on the given info in the family tree.

-

The user can easily query the Prolog system about relations defined in the program.

-

A Prolog program consists of clauses terminated by a full stop.

-

The arguments of relations can (among other things) be: concrete objects, or constants (such as pat and jim), or general objects such as X and Y. Objects of the first kind in our program are called atoms. Objects of the second kind are called variables.

-

Questions to the system consist of one or more goals.

Some facts can be written in two different ways, like sex of family members can be written in either of the forms −

-

female(pam).

-

male(tom).

-

male(bob).

-

female(liz).

-

female(pat).

-

female(ann).

-

male(jim).

Or in the below form −

-

sex( pam, feminine).

-

sex( tom, masculine).

-

sex( bob, masculine).

-

… and so on.

Now if we want to make mother and sister relationship, then we can write as given below −

In Prolog syntax, we can write −

-

mother(X,Y) :- parent(X,Y), female(X).

-

sister(X,Y) :- parent(Z,X), parent(Z,Y), female(X), X == Y.

Now let us see the practical demonstration −

Knowledge Base (family.pl)

female(pam). female(liz). female(pat). female(ann). male(jim). male(bob). male(tom). male(peter). parent(pam,bob). parent(tom,bob). parent(tom,liz). parent(bob,ann). parent(bob,pat). parent(pat,jim). parent(bob,peter). parent(peter,jim). mother(X,Y):- parent(X,Y),female(X). father(X,Y):- parent(X,Y),male(X). haschild(X):- parent(X,_). sister(X,Y):- parent(Z,X),parent(Z,Y),female(X),X==Y. brother(X,Y):-parent(Z,X),parent(Z,Y),male(X),X==Y.

Output

| ?- [family]. compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family.pl for byte code... D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family.pl compiled, 23 lines read - 3088 bytes written, 9 ms yes | ?- parent(X,jim). X = pat ? ; X = peter yes | ?- mother(X,Y). X = pam Y = bob ? ; X = pat Y = jim ? ; no | ?- haschild(X). X = pam ? ; X = tom ? ; X = tom ? ; X = bob ? ; X = bob ? ; X = pat ? ; X = bob ? ; X = peter yes | ?- sister(X,Y). X = liz Y = bob ? ; X = ann Y = pat ? ; X = ann Y = peter ? ; X = pat Y = ann ? ; X = pat Y = peter ? ; (16 ms) no | ?-

Now let us see some more relationships that we can make from the previous relationships of a family. So if we want to make a grandparent relationship, that can be formed as follows −

We can also create some other relationships like wife, uncle, etc. We can write the relationships as given below −

-

grandparent(X,Y) :- parent(X,Z), parent(Z,Y).

-

grandmother(X,Z) :- mother(X,Y), parent(Y,Z).

-

grandfather(X,Z) :- father(X,Y), parent(Y,Z).

-

wife(X,Y) :- parent(X,Z),parent(Y,Z), female(X),male(Y).

-

uncle(X,Z) :- brother(X,Y), parent(Y,Z).

So let us write a prolog program to see this in action. Here we will also see the trace to trace-out the execution.

Knowledge Base (family_ext.pl)

female(pam). female(liz). female(pat). female(ann). male(jim). male(bob). male(tom). male(peter). parent(pam,bob). parent(tom,bob). parent(tom,liz). parent(bob,ann). parent(bob,pat). parent(pat,jim). parent(bob,peter). parent(peter,jim). mother(X,Y):- parent(X,Y),female(X). father(X,Y):-parent(X,Y),male(X). sister(X,Y):-parent(Z,X),parent(Z,Y),female(X),X==Y. brother(X,Y):-parent(Z,X),parent(Z,Y),male(X),X==Y. grandparent(X,Y):-parent(X,Z),parent(Z,Y). grandmother(X,Z):-mother(X,Y),parent(Y,Z). grandfather(X,Z):-father(X,Y),parent(Y,Z). wife(X,Y):-parent(X,Z),parent(Y,Z),female(X),male(Y). uncle(X,Z):-brother(X,Y),parent(Y,Z).

Output

| ?- [family_ext]. compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family_ext.pl for byte code... D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family_ext.pl compiled, 27 lines read - 4646 bytes written, 10 ms | ?- uncle(X,Y). X = peter Y = jim ? ; no | ?- grandparent(X,Y). X = pam Y = ann ? ; X = pam Y = pat ? ; X = pam Y = peter ? ; X = tom Y = ann ? ; X = tom Y = pat ? ; X = tom Y = peter ? ; X = bob Y = jim ? ; X = bob Y = jim ? ; no | ?- wife(X,Y). X = pam Y = tom ? ; X = pat Y = peter ? ; (15 ms) no | ?-

Tracing the output

In Prolog we can trace the execution. To trace the output, you have to enter into the trace mode by typing “trace.”. Then from the output we can see that we are just tracing “pam is mother of whom?”. See the tracing output by taking X = pam, and Y as variable, there Y will be bob as answer. To come out from the tracing mode press “notrace.”

Program

| ?- [family_ext].

compiling D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family_ext.pl for byte code...

D:/TP Prolog/Sample_Codes/family_ext.pl compiled, 27 lines read - 4646 bytes written, 10 ms

(16 ms) yes

| ?- mother(X,Y).

X = pam

Y = bob ? ;

X = pat

Y = jim ? ;

no

| ?- trace.

The debugger will first creep -- showing everything (trace)

yes

{trace}

| ?- mother(pam,Y).

1 1 Call: mother(pam,_23) ?

2 2 Call: parent(pam,_23) ?