Последнее обновление: 23.03.2023

-

Глава 1. Введение в Java

-

Язык программирования Java

-

Первая программа на Java в Windows

-

Первая программа в IntelliJ IDEA

-

Первая программа в NetBeans

-

Первая программа в Eclipse

-

-

Глава 2. Основы программирования на Java

-

Структура программы

-

Переменные и константы

-

Типы данных

-

Консольный ввод/вывод в Java

-

Арифметические операции

-

Поразрядные операции

-

Условные выражения

-

Операции присваивания и приоритет операций

-

Преобразования базовых типов данных

-

Условные конструкции

-

Циклы

-

Массивы

-

Методы

-

Параметры методов

-

Оператор return. Результат метода

-

Перегрузка методов

-

Рекурсивные функции

-

Введение в обработку исключений

-

-

Глава 3. Классы. Объектно-ориентированное программирование

-

Классы и объекты

-

Пакеты

-

Модификаторы доступа и инкапсуляция

-

Статические члены и модификатор static

-

Объекты как параметры методов

-

Внутренние и вложенные классы

-

Наследование

-

Абстрактные классы

-

Иерархия наследования и преобразование типов

-

Интерфейсы

-

Интерфейсы в механизме обратного вызова

-

Перечисления enum

-

Класс Object и его методы

-

Обобщения (Generics)

-

Ограничения обобщений

-

Наследование и обобщения

-

Ссылочные типы и клонирование объектов

-

Records

-

-

Глава 4. Обработка исключений

-

Оператор throws

-

Классы исключений

-

Создание своих классов исключений

-

-

Глава 5. Коллекции

-

Типы коллекций. Интерфейс Collection

-

Класс ArrayList и интерфейс List

-

Очереди и класс ArrayDeque

-

Класс LinkedList

-

Интерфейс Set и класс HashSet

-

SortedSet, NavigableSet, TreeSet

-

Интерфейсы Comparable и Comporator. Сортировка

-

Интерфейс Map и класс HashMap

-

Интерфейсы SortedMap и NavigableMap. Класс TreeMap

-

Итераторы

-

-

Глава 6. Потоки ввода-вывода. Работа с файлами

-

Потоки ввода-вывода

-

Чтение и запись файлов. FileInputStream и FileOutputStream

-

Закрытие потоков

-

Классы ByteArrayInputStream и ByteArrayOutputStream

-

Буферизованные потоки BufferedInputStream и BufferedOutputStream

-

Форматируемый вывод. PrintStream и PrintWriter

-

Классы DataOutputStream и DataInputStream

-

Чтение и запись текстовых файлов

-

Буферизация символьных потоков. BufferedReader и BufferedWriter

-

Сериализация объектов

-

Класс File. Работа с файлами и каталогами

-

Работа с ZIP-архивами

-

Класс Console

-

-

Глава 7. Работа со строками

-

Введение в строки. Класс String

-

Основные операции со строками

-

StringBuffer и StringBuilder

-

Регулярные выражения

-

-

Глава 8. Лямбда-выражения

-

Введение в лямбда-выражения

-

Лямбды как параметры и результаты методов

-

Встроенные функциональные интерфейсы

-

-

Глава 9. Многопоточное программирование

-

Класс Thread

-

Создание и выполнение потоков

-

Завершение и прерывание потока

-

Синхронизация потоков. Оператор synchronized

-

Взаимодействие потоков. Методы wait и notify

-

Семафоры

-

Обмен между потоками. Класс Exchanger

-

Класс Phaser

-

Блокировки. ReentrantLock

-

Условия в блокировках

-

-

Глава 10. Stream API

-

Введение в Stream API

-

Создание потока данных

-

Фильтрация, перебор элементов и отображение

-

Сортировка

-

Получение подпотока и объединение потоков

-

Методы skip и limit

-

Операции сведения

-

Метод reduce

-

Тип Optional

-

Метод collect

-

Группировка

-

Параллельные потоки

-

Параллельные операции над массивами

-

-

Глава 11. Модульность

-

Создание модуля

-

Зависимые модули

-

Взаимодействие между модулями

-

-

Глава 12. Дополнительные классы

-

Математические вычисления и класс Math

-

Большие числа BigInteger и BigDecimal

-

Работа с датами. LocalDate

-

- Глава 1. Введение в Java

- Язык программирования Java

- Первая программа на Java в Windows

- Первая программа в IntelliJ IDEA

- Первая программа в NetBeans

- Первая программа в Eclipse

- Глава 2. Основы программирования на Java

- Структура программы

- Переменные и константы

- Типы данных

- Консольный ввод/вывод в Java

- Арифметические операции

- Поразрядные операции

- Условные выражения

- Операции присваивания и приоритет операций

- Преобразования базовых типов данных

- Условные конструкции

- Циклы

- Массивы

- Методы

- Параметры методов

- Оператор return. Результат метода

- Перегрузка методов

- Рекурсивные функции

- Введение в обработку исключений

- Глава 3. Классы. Объектно-ориентированное программирование

- Классы и объекты

- Пакеты

- Модификаторы доступа и инкапсуляция

- Статические члены и модификатор static

- Объекты как параметры методов

- Внутренние и вложенные классы

- Наследование

- Абстрактные классы

- Иерархия наследования и преобразование типов

- Интерфейсы

- Интерфейсы в механизме обратного вызова

- Перечисления enum

- Класс Object и его методы

- Обобщения (Generics)

- Ограничения обобщений

- Наследование и обобщения

- Ссылочные типы и клонирование объектов

- Records

- Глава 4. Обработка исключений

- Оператор throws

- Классы исключений

- Создание своих классов исключений

- Глава 5. Коллекции

- Типы коллекций. Интерфейс Collection

- Класс ArrayList и интерфейс List

- Очереди и класс ArrayDeque

- Класс LinkedList

- Интерфейс Set и класс HashSet

- SortedSet, NavigableSet, TreeSet

- Интерфейсы Comparable и Comporator. Сортировка

- Интерфейс Map и класс HashMap

- Интерфейсы SortedMap и NavigableMap. Класс TreeMap

- Итераторы

- Глава 6. Потоки ввода-вывода. Работа с файлами

- Потоки ввода-вывода

- Чтение и запись файлов. FileInputStream и FileOutputStream

- Закрытие потоков

- Классы ByteArrayInputStream и ByteArrayOutputStream

- Буферизованные потоки BufferedInputStream и BufferedOutputStream

- Форматируемый вывод. PrintStream и PrintWriter

- Классы DataOutputStream и DataInputStream

- Чтение и запись текстовых файлов

- Буферизация символьных потоков. BufferedReader и BufferedWriter

- Сериализация объектов

- Класс File. Работа с файлами и каталогами

- Работа с ZIP-архивами

- Класс Console

- Глава 7. Работа со строками

- Введение в строки. Класс String

- Основные операции со строками

- StringBuffer и StringBuilder

- Регулярные выражения

- Глава 8. Лямбда-выражения

- Введение в лямбда-выражения

- Лямбды как параметры и результаты методов

- Встроенные функциональные интерфейсы

- Глава 9. Многопоточное программирование

- Класс Thread

- Создание и выполнение потоков

- Завершение и прерывание потока

- Синхронизация потоков. Оператор synchronized

- Взаимодействие потоков. Методы wait и notify

- Семафоры

- Обмен между потоками. Класс Exchanger

- Класс Phaser

- Блокировки. ReentrantLock

- Условия в блокировках

- Глава 10. Stream API

- Введение в Stream API

- Создание потока данных

- Фильтрация, перебор элементов и отображение

- Сортировка

- Получение подпотока и объединение потоков

- Методы skip и limit

- Операции сведения

- Метод reduce

- Тип Optional

- Метод collect

- Группировка

- Параллельные потоки

- Параллельные операции над массивами

- Глава 11. Модульность

- Создание модуля

- Зависимые модули

- Взаимодействие между модулями

- Глава 12. Дополнительные классы

- Математические вычисления и класс Math

- Большие числа BigInteger и BigDecimal

- Работа с датами. LocalDate

Помощь сайту

YooMoney:

410011174743222

Перевод на карту

Номер карты:

4048415020898850

Дисклаймер

Сразу хочу вас предупредить, чтобы стать настоящим java разработчиком с нуля вам нужно будет потратить в разы больше его времени. Как преподаватель java в Сбер Университете, по своему опыту могу сказать, чтобы точно получить хорошую работу на изучение языка и его инфраструктуры вы должны потратить 5-6 месяцев – при этом заниматься минимум 40 часов в неделю.

Начинаем!

История языка и предпосылки к лидерству

Почему Java так популярен? Во-первых это старый язык по меркам сферы ИТ. Ему уже более 25 лет. За это время было написано огромное количество приложений и библиотек, сформировано, наверное, самое многочисленное комьюнити программистов, которое поможет найти ответ на любой вопрос. Во-вторых java создавался с прицелом на высокую надежность: в то время доминировали языки C и C++, которые обладали высоким порогом входа – нужно было внимательно следить за за каждой строчкой. Легко можно было выстрелить себе в ногу, неправильно использовав множественное наследование, не почистив правильно память и т.д.

В Java учли эти ошибки. В нем сделали удобный автоматический сборщик мусора, добавили развитую систему исключений: появились исключения типа checked, которые существенно увеличили надежность кода. Были созданы более удобные механизмы работы с многопоточностью, а так же использована статическая типизация.

Все это позволило сделать Java в свое время самым надежным языком на рынке, поэтому многие компании выбрали его в качестве основного и не прогадали.

Одной из киллер-фич был подход к исполнению кода. Он не компилировался напрямую в бинарники. Компилятор создавал на основе исходного кода байт-код, который уже в свою очередь с помощью специального приложения – JAVA машины исполнялся на компьютере. Такой подход давал ряд существенных преимуществ: программист мог запустить один и тот же код по разными операционными системами, процессорами вообще без каких-либо изменений!

Не надо было перекомпилировать код под новую платформу, соответственно администратор без привлечения программистов мог осуществить перенос приложения на новый сервис с абсолютно другой архитектурой за пару часов.

Второе важное преимущество – с каждой новой версией Java-машина получала новые возможности, которые позволяли оптимизировать код на лету. Один и тот же код с каждой новой версией выполнялся все быстрее и быстрее вообще без вмешательства программистов!

Недавно java перешла на новый релизный цикл – каждая новая версия выходит через полгода. Это позволяет быстрее доставлять новые возможности в язык и практически полностью сократить отставание языка от других jvm языков.

Возможно, сейчас многие из преимуществ непонятны, но изучая java вы поймете, насколько они замечательные и как Java в свое время определила развитие ИТ.

Подготовка окружения

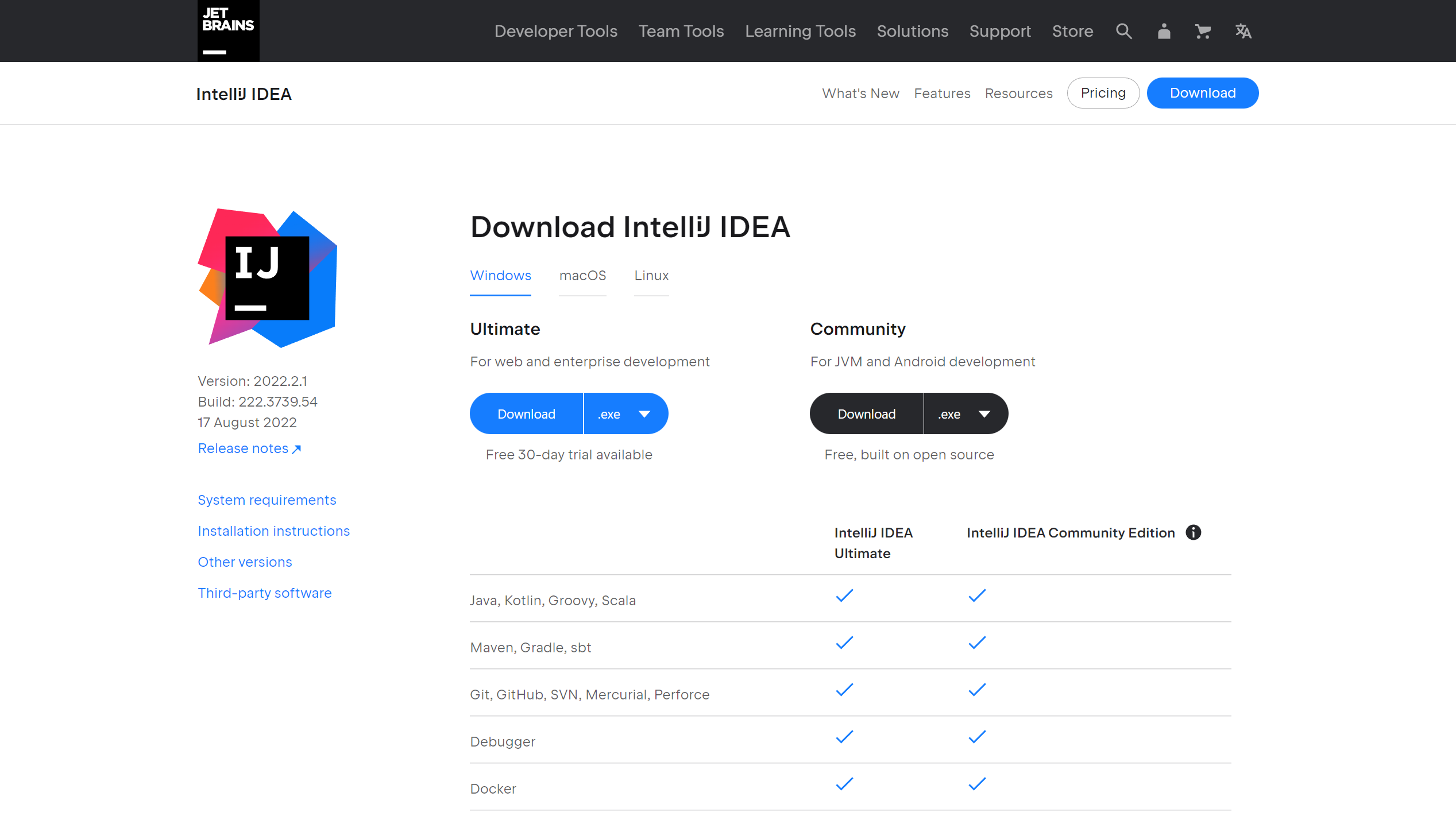

В первую очередь нам надо скачать JDK – это та самая виртуальная машина, а также набор утилит, которые позволят собирать код. После чего мы уже можем начинать программировать в любимом редакторе. Если у вас такового не имеется, могу порекомендовать скачать и установить – IntelliJ IDEA Community. Это самый популярный редактор исходного кода на Java, базовая версия которого распространяется бесплатно.

После того как мы скачали все и запустили редактор, приступим к изучению.

В java все является объектом. Что такое объект? Это некоторая сущность в которой описано ее состояние с помощью каких-либо переменных, а также описано ее поведение с помощью функций. Рассмотрим все на примере из реального мира.

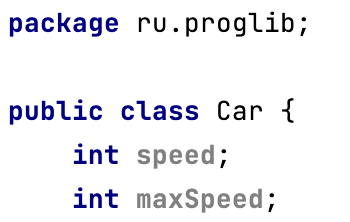

У нас есть автомобиль, у него много характеристик. Мы абстрагируемся от них, нас интересует только два параметра: текущая скорость и максимальная скорость. В мире объектно-ориентированного программирования этот подход так и называется – абстракция. Какое поведение мы ожидаем от автомобиля? Всего два – начать движение и остановиться. Напишем этот код на java в файле с именем Car.java:

public class Car {

int speed;

int maxSpeed;

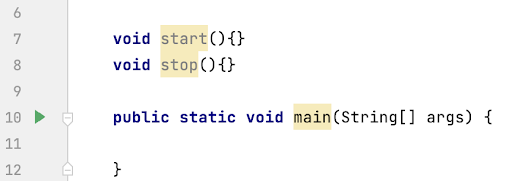

void start(){}

void stop(){}

}

Здесь мы описали шаблон будущего объекта – класс. У него есть две переменные состояния – speed и maxSpeed, а также две функции, которые описывают поведение объекта.

Теперь приложение нужно запустить, для этого Java надо подсказать, где находится точка входа в него. Для этого существует особое соглашение – нужно добавить в описание любого объекта метод:

public static void main(String[] args) {

}

Именно, тот код, который мы в нем укажем и начнет выполняться.

Выполним теперь в консоли следующие команды:

javac Car.java

java Car

Либо, что в разы проще, просто нажимаем зеленую стрелочку около метода и редакторе:

Наше приложение запустилось, но ничего не произошло, потому что мы не добавили никакой логики в метод. Добавим простой вывод на консоль текста:

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello");

}

Результат выполнения виден на консоли.

Отмечу, что каждый файл может содержать только один публичный класс. То есть ключевое слово public вместе со словом class.

Ключевое слово public – это так называемый модификатор доступа. Оно определяет уровень доступности этого класса/метода/переменной из других частей программы.

Имя файла должно совпадать с именем класса, включая регистр, и иметь расширение .java. Ключевое слово static, говорит компилятору о том, что данный метод/переменная принадлежит именно шаблону объекта, то есть классу, а не конкретному объекту.

Пока не будем особо на это заострять внимание.

Пакеты в java

Стоит отметить, что часто в программах классы называют одинаково, поэтому была предложена идея их раскладывать по папкам, чтобы не было конфликта имен. Папка, в которой находится класс указывается в самом верху файла:

Создатели предложили называть эти папки как доменные имена в интернете, чтобы точно разграничить их, но это не обязательно, вы можете называть их как захотите.

Это так же позволяет легко импортировать чужие классы в свой код:

package ru.proglib;

import java.util.Random; // импортируем описание класса из пакета java.util.

public class Import {

public static void main(String[] args) {

var random = new Random();

System.out.println(random.nextInt()); // выводим на экран случайное число

}

}

В нашем пакете нет определения класса Random, поэтому я воспользовался ключевым словом import, чтобы его добавить в нашу программу. Теперь я могу с ним работать. Используя ключевое слово new я создаю на основе класса объект random, который могу использовать в дальнейшем коде. Далее у объекта я вызываю метод, nextInt который описывает следующее поведение объекта: объект возвращает из метода натуральное число, которое произвольно каким-то образом у себя генерирует. Мы не знаем как именно это происходит – мы знаем только то, что в результате вызова этого метода мы получим какое-то целое число типа int. В объектно ориентированном программировании этот прием называется инкапсуляцией – когда объект внутри себя, основываясь на своем состоянии генерирует некий результат, при этом пользователь данного метода не знает как это работает под капотом.

Продолжим далее разбираться с кодом, который был представлен выше. Начнем с самого простого. Если мы хотим добавить какое-то пояснение к коду, мы можем вставить в любую строчку два косых слеша и весь текст после них будет отброшен при компиляции программы, но при просмотре исходного кода он виден.

Создание объектов

В коде у нас была следующая строка:

Random random = new Random();

Что она делает?

Здесь мы с помощью ключевого слова new создаем новый объект из его шаблона. Мы указываем, что в своем коде мы будем использовать имя random для обращения к этому объекту. В последней строке мы вызываем метод nextInt который приводит к тому, что в нашу программу возвращается какое-то число, после чего это же число мы передаем в метод println который уже выводит его на экран.

Попробуем для создать класс нашего автомобиля и задать ему поведение:

public class Car {

int speed;

int maxSpeed;

void start() {

System.out.println("Я начал ехать");

}

void stop() {

System.out.println("Я остановился");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var myCar = new Car();

myCar.start();

myCar.stop();

}

}

Запустите код и посмотрите, что будет выведено на консоль.

Теперь вернемся к нашим переменным состояния объекта.

Примитивные типы в java

Компьютеры работают в основном с числами, поэтому были придуманы несколько ключевых слов, которые обозначают разные типы данных, по другому их называют примитивные типы данных:

| Ключевое слово | Тип | Пример |

| boolean | true или false (8-bit число) | true |

| byte | 8-bit число | 123 |

| short | 16-bit число | 123 |

| int | 32-bit число | 123 |

| long | 64-bit число | 123L |

| float | 32-bit число | 123.0f |

| double | 64-bit число | 123.0 |

| char | 16-bit число | ‘a’ |

Так как компьютеры развивались постепенно, то на разных этапах своей жизни они могли хранить число, которое не выше разряда процессора, на котором они работают.

Поэтому появилась такая битовая таблица различных чисел. В нашем случае мы будем использовать числа типа int, которые могут быть описаны 32 битами в памяти компьютера. То есть наши числа будут лежать в промежутке -2,147,483,648 (-2^31) to 2,147,483,647 (2^31-1).

Конструкторы объектов

Теперь мы хотим, чтобы наше поведение зависело и от внутреннего состояния объекта. Для этого его надо как-то задать. Посмотрим как это можно сделать.

public class Car {

int speed;

int maxSpeed;

public Car(int speed, int maxSpeed) {

this.speed = speed;

this.maxSpeed = maxSpeed;

System.out.println("Объект готов");

}

void start() {

System.out.println("Я начал ехать");

System.out.println(speed);

}

void stop() {

System.out.println("Я остановился");

System.out.println(maxSpeed);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

myCar.start();

myCar.stop();

}

}

Мы добавили в наш код специальный код – конструктор. Он позволяет инициализировать объект перед тем как начать им пользоваться. При этом при создании объекта в методе main я добавил два натуральных числа, которые соответственно инициализировали состояние объекта. В конструкторе мы можем указать любую логику, которую необходимо выполнить при создании объекта.

Если вы запустите приложение, то увидите, что кроме строк на экран выводятся и числа – как раз те, которые мы передали в конструкторе. Теперь наш объект инициализирован – у него есть какое-то внутреннее состояние.

Ссылки vs примитивные типы

Теперь рассмотрим ключевое различие между ссылками на объект, которые мы использовали для работой с объектами и примитивными типами. Для ссылок мы можем написать так:

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

myCar = null;

Мы приравняли наш указатель на объект к ключевому слову null, которое говорит виртуальной машине, что по данному указателю уже нельзя обращаться к объекту, то есть вызов myCar.start(); приведет к ошибке. Что произойдет с нашим объектом, который мы создали? В виртуальной машине java запускается сборщик мусора, который обнаружит, что данный объект живет без какой либо ссылки и удалит его из памяти – то есть сотрет его в оперативной памяти.

Но подобное не работает с примитивными типами:

int x = null;

Подобный код вызовет ошибку.

Также стоит отметить, что строки также являются классами, но при этом для них в языке сделаны существенные изменения.

Строки описываются классом String. Посмотрим какие исключения для них есть:

var str = "Я остановился";

var srt2 = new String("Я остановился");

Это единственный класс, который мы можем создать без оператора new.

Кроме того, строки можно складывать друг с другом или другими примитивными типами, но не вычитать, делить и т.п.:

System.out.println("Я начал ехать" + "в направлении М1");

System.out.println("Я начал ехать" + "в направлении М1 со скоростью " + speed);

Добавьте данные строчки в наш код и вы увидите, что все прекрасно работает. Но повторюсь, что подобное исключение сделано только для одного класса – String, потом что строки очень часто используются.

Операторы в java

Раз мы упомянули операторы, давайте посмотрим какие предлагает java.

Унарный оператор – это оператор, для работы которого требуется только один операнд, или переменная, часто выполняют простые операции.

| Оператор | Описание | Пример |

| ! | Инвертирует логическое значение булевой функции | !true будет равно false |

| + либо — | Указывает на знак числа | -123 |

| ++ | Добавляет к числу единицу | var i = 5; i++; //i будет равно 6 |

| — | Отнимает от числа единицу | var i = 5; i—; //i будет равно 4 |

Далее мы перейдем к операторам, принимающим два аргумента, которые называются бинарными операторами. Бинарные операторы являются самыми распространенными операторами в языке Java. Ранее мы уже познакомились с оператором сложения для строк.

Они могут использоваться для выполнения математических операций над переменными, создания логических выражений и выполнения базовых присваиваний переменных.

| Оператор | Описание | Пример |

| + | Cложение | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i + k) |

| — | Вычитание | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i – k) |

| * | Умножение | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i * k) |

| / | Деление | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i / k) |

| % | Взятие по модулю | var i = 15; var k = 6; System.out.println(i % k) |

Если мы пишем сложное математическое выражение, то лучше пользоваться скобками:

var x = 5 * (6 – 8);

Завершить секцию с операторами я хотел бы таблицей с условными операторами, результат работы которых true либо false:

| Оператор | Описание | Пример |

| == | Сравнение на равенство | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i == k) |

| < либо <= | Меньше, меньше либо равно | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i < k) |

| > либо >= | Больше, больше либо равно | var i = 5; var k = 6; System.out.println(i >= k) |

| && | Логическое и. В обоих частях должно быть true, чтобы оператор вернул true | System.out.println(true && true) |

| || | Логическое и. Хотя бы в одной части должно быть true, чтобы оператор вернул true | System.out.println(false || true) |

Мы познакомились с самыми популярными операторами в java, настало время их использовать.

Мы хотим, чтобы наш автомобиль мог менять свое поведение, а именно изменять текущую скорость, которую мы задали при его создании.

Добавим новый метод, который будет это делать:

void setSpeed(int speed){

this.speed = speed;

}

Но мы не хотим, чтобы кто-то, кто пользуется нашим классом мог устанавливать скорость выше максимальной.

Условные выражения

Для того, чтобы наложить какие-либо ограничения на переменную, нам необходимо провести проверку, для этого нам понадобиться использовать условное выражение if:

void setSpeed(int speed) {

if (speed < maxSpeed) {

this.speed = speed;

}

}

В круглых скобках мы помещаем условие, которое должно вернуть либо true либо false, а в фигурных мы добавляем тот код, который будет выполнен если условие правдиво.

Так же, если условие вернуло false мы можем добавить с помощью ключевого слова else еще один блок кода, который выполняем в таком случае:

void setSpeed(int speed) {

if (speed < maxSpeed) {

this.speed = speed;

}

else {

System.out.println("Вы передали слишком большую скорость");

}

}

Циклы

Что делать, если мы хотим повторять какой-то блок кода много раз? Если вместо if написать while у нас получится самый простой цикл, который будет выполняться до тех пор пока выражение в круглых скобках истинно или не произойдет прерывания цикла с помощью ключевого слова break, либо пока программа не завершиться, например из другого потока. Выглядеть это будет так:

public static void main(String[] args) {

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

var i = 0;

while (i < 10){

myCar.start();

i++;

}

}

В данном случае, мы создаем некую примитивную переменную i изначально равную 0. В цикле у нас есть условие того, что она меньше 10, если это не так, то код в фигурных скобках выполняться не будет. В них же мы увеличиваем значение i на единицу, если бы мы этого не делали, то выполнялся бы цикл вечно. Запустите программу и посмотрите, что будет выведено на экран и сколько раз.

Для того, чтобы отделить те логику работы цикла от нашего кода был создан цикл for.

Найдите различия:

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

myCar.start();

}

В круглых скобках у нас создается счетчик, передается условие цикла и рецепт, что делать со счетчиком на каждой итерации. Согласитесь, так код выглядит более компактно и логика управления циклом не перемешивается с нашей логикой.

если не передать никаких условий, то получится бесконечный цикл:

for( ; ; ) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

Выйти из него никак нельзя, только прервав работу приложения с помощью средств операционной системы. Мы можем прервать его работу с помощью ключевого слова break:

for( ; ; ) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

break;

}

Сообщение будет выведено на консоль и на этом месте цикл остановится.

Массивы и коллекции

В своем проекте мы создали только один автомобиль, давайте теперь создадим несколько и поместим их в какое-то хранилище.

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

var myCar2 = new Car(10, 50);

var garage = new Car[2];

garage[0] = myCar;

garage[1] = myCar2;

for (Car car : garage) {

car.start();

}

В примере выше мы создали два автомобиля, потом создали массив из указателей на объекты класса Car размером 2 и положили в него указатели на наши объекты. Как видно, отсчет ячеек массива начинается с 0. После чего мы использовали специальную модификацию цикла for для массивов и коллекций, который позволяет пройтись по всем элементам и совершить с ними какую-то логику.

То есть теперь у нас есть объект, который может хранить в себе несколько указателей на другие объекты, но работать с массивами не удобно. Нужно знать заранее точный размер и в какие ячейки, что нужно записывать. Поэтому сейчас самый востребованный метод хранения данных – коллекции.

Перепишем наш код с помощью коллекций:

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

var myCar2 = new Car(10, 50);

var garage = new ArrayList<Car>();

garage.add(myCar);

garage.add(myCar2);

for (Car car : garage) {

car.start();

}

Как вы можете видеть, код не сильно изменился, но пропали эти неуклюжие записи указателей в конкретные ячейки. Теперь все сохраняется автоматически.

Для объявления коллекции мы написали так:

var garage = new ArrayList<Car>();

Что это значит? Здесь мы говорим, что будем использовать коллекцию на основе массива и что в нашей коллекции будут лежать объекты типа Car.

Самое важное, что мы не задали размер нашей коллекции. Так как она позволяет добавлять в себя любое число элементов, которые могут поместиться в оперативной памяти вашего компьютера.

Коллекция типа HashSet (множество) не позволит положить в себя два одинаковых значения, сравните выводы:

var garage = new HashSet<Car>();

garage.add(myCar);

garage.add(myCar);

garage.add(myCar2);

for (Car car : garage) {

car.start();

}

А потом замените первую строку

var garage = new ArrayList<Car>();

Кроме списка так же популярна коллекция Map, она позволяет присваивать объектам ключи и потом получать эти объекты по уникальному ключу:

var myCar = new Car(100, 500);

var myCar2 = new Car(10, 50);

var garage = new HashMap<String, Car>();

garage.put("Мой авто", myCar);

garage.put("Мой второй авто", myCar2);

garage.get("Мой второй авто").start();

Я указал строку в качестве ключа – очень частая практика. И положил в коллекцию два своих объекта. Потом я по ключу достал свой объект и вызвал его метод.

Могу сказать, что коллекции – это то, чем вы будете пользоваться всегда в своей работе, поэтому их надо знать. Здесь я рассказал лишь о трех из них, которые используются в 99% случаев, при том не рассказав какие дополнительные методы они несут в себе.

Исключения

Чтобы произошло, если бы я написал свой запрос так:

garage.get("второй авто").start();

То на консоли увидел бы следующее:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.NullPointerException

at ru.proglib.Car.main(Car.java:42)

Возникла исключительная ситуация и программа прервала свою работу. Так как метод get вернул null о котором мы говорили ранее. Соответственно у нас не было объекта на котором мы могли бы вызвать метод. Для предотвращения таких ситуаций был придумал блок try/catch. Посмотрим как он помог бы решить нашу проблему:

try {

garage.get("второй авто").start();

}catch (NullPointerException exception){

System.out.println("В словаре нет автомобиля с таким ключем");

}

После try я в фигурных скобках пишу код, в качестве которого не уверен. В блоке круглых скобок catch я указываю какого типа ошибки могут возникнуть. Ошибки также являются в java объектами. Соответственно в фигурных скобках я указываю ту логику, которая будет выполнена при возникновении исключительной ситуации.

Вывод

Наше беглое знакомство с Java заканчивается. В этом материале мы рассмотрели лишь малую часть возможностей языка и его конструкций. Но я надеюсь, вы поняли, что на нем можно писать довольно лаконично и емко, при том программы, которые вы будете создавать будут отличаться надежностью и мультиплатформенностью из коробки. Java сейчас один из самых востребованных языков в мире разработки и если вы выберете его в качестве своего основного, то вы однозначно выиграете от этого решения. Ниже я привел лучше ресурсы, откуда можно черпать свои знания. Удачного обучения!

Дополнительные материалы:

- Очень рекомендую ознакомится с заметкой ТОП-10 лучших книг по Java для программистов ( https://proglib.io/p/java-books-2019). В ней вы найдете поборку из прекрасных книг по java.

- Если необходимо узнать какую-то информацию о бзовых возможностях java, то лучше официально документации ничего нет – https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/16/

- А если вам нужно усваивать материал через видео, то нет ничего лучше, чем лекции, которые читает Java Champion.

***

Мне всё еще непонятно, с чего начинать путь в IT. Что посоветуете?

Стоит подумать, как построить свой путь в индустрию, чтобы получить качественные знания и устроиться на работу.

Онлайн-университет Skypro помогает новичкам в IT комфортно сменить сферу деятельности. Курс «Java-разработчик» построен так, чтобы дать полноценный взгляд на IT и базовые знания для работы младшим специалистом. Вы научитесь:

- писать код на языках Java и SQL;

- управлять схемами баз данных;

- собирать проекты на Maven и Spring;

- работать с кешем и потоками.

На протяжении всего обучения студентов поддерживают наставники и обучают топовые специалисты рынка. Если вы не устроитесь на работу в течение четырех месяцев после окончания обучения, Skypro вернет деньги — это прописано в договоре.

Юрий Пономарев

консультант по программным продуктам Oracle Центра технической поддержки компании РДТЕХ

Java – один из самых востребованных языков программирования в мире и один из двух официальных языков программирования, используемых в разработке Android (другой – Kotlin). Разработчики, знакомые с Java, весьма востребованы и способны создавать широкий спектр различных приложений, игр и инструментов. С помощью этой краткой статьи по Java для начинающих вы сможете сделать свои первые шаги к тому, чтобы стать одним из таких разработчиков. Мы рассмотрим все, что вам нужно знать, чтобы начать работу, и поможем вам создать свое первое простое приложение.

Java-это объектно-ориентированный язык программирования, разработанный компанией Sun Microsystems в 1990-х годах (позже купленной Oracle).

Понятие «объектно-ориентированный» относится к способу написания структурного кода Java, а именно: разделение кода на так называемые «классы», которые запускаются вместе, чтобы обеспечить согласованное порождение объектов. Мы обсудим это позже, но достаточно сказать, что это приводит к универсальному и организованному коду, который легко редактировать и перепрофилировать.

Java находится под влиянием C и C++, поэтому она имеет много общего с этими языками (и C#). Одним из больших преимуществ Java является то, что он «платформенно-независимый». Это означает, что код, который вы пишете на одной платформе, можно легко запустить на другой. Это называется принципом «пишем один раз, запускаем где угодно» (хотя на практике это не всегда так просто, как кажется).

Чтобы запустить и использовать Java, вам нужно три вещи:

- JDK – Java Development Kit

- JRE – Java Runtime Environment

- JVM – Java Virtual Machine

Виртуальная машина Java (JVM) гарантирует, что у ваших приложений Java есть доступ к минимальным ресурсам, необходимым для их запуска. Именно благодаря JVM программы Java так легко запускаются на разных платформах.

Среда исполнения Java (JRE) предоставляет собой «контейнер» для всех этих элементов и кода для запуска приложения. JDK – это «компилятор», который интерпретирует сам код и выполняет его. В JDK также есть инструменты разработчика, необходимые для написания кода Java (как и следует из названия).

Хорошая новость заключается в том, что разработчикам нужно только позаботиться о загрузке JDK, поскольку он поставляется вместе с двумя другими компонентами.

Как начать писать на Java

Если вы планируете разрабатывать приложения на Java на своем настольном компьютере, то вам нужно будет загрузить и установить JDK.

Вы можете получить последнюю версию JDK непосредственно с сайта Oracle. Как только вы установите его, ваш компьютер будет иметь возможность понимать и запускать код на Java. Тем не менее, вам все равно понадобится некоторое вспомогательное ПО, чтобы было действительно удобно писать код. Это так называемая «интегрированная среда разработки» или IDE: интерфейс, используемый разработчиками для ввода текста кода и вызова JDK.

При разработке для Android вы будете использовать IDE Android Studio. Она не только послужит интерфейсом для кода на Java (или Kotlin), но и станет мостом для доступа к специфичным для Android вызовам из SDK.

Для целей нашего краткого руководства по Java может быть и проще написать свой код непосредственно в приложении-компиляторе Java. Они могут быть скачаны для Android и iOS, можно даже найти веб-приложения, которые работают в вашем браузере. Эти инструменты предоставляют все необходимое в одном месте и позволяют сразу начать тестирование кода. Например, compilejava.net.

Насколько легко научиться программированию на Java?

Если вы новичок в разработке на Java, то ваши опасения вполне понятны. Так насколько же легко изучить Java?

Этот вопрос имеет несколько субъективную природу, но лично я бы отнес Java к языкам, не самым простым для изучения. Хотя он проще, чем C++, и часто описывается как более удобный для пользователя, но он, безусловно, не столь прост, как такие его конкуренты, как Python или BASIC, которые больше подходят для изучения начинающим программистам.

C# также немного проще по сравнению с Java, хотя они очень похожи.

Конечно, задавшись конкретной целью – стать разработчиком приложений для Android, – проще всего сразу начать с языка, который уже поддерживается этой платформой.

У языка Java есть свои особенности, но его, безусловно, можно изучить, и как только вы его освоите, вам откроется множество возможностей. А поскольку Java имеет много общего с C и C#, вы сможете перейти на эти языки без особых усилий.

Каков синтаксис Java?

Прежде чем мы погрузимся в самую суть этого руководства по Java для начинающих, стоит уделить некоторое время изучению синтаксиса Java.

Синтаксис Java относится к способу написания конкретных алгоритмов. Java очень принципиален в этом вопросе, и, если вы не пишете код определенным образом, то ваша программа не будет работать!

На самом деле я написал целую статью о синтаксисе Java для разработки Android, кратко перечислю особенности синтаксиса:

- Большинство строк должно заканчиваться точкой с запятой «;».

- Исключение составляет строка, открывающая новый блок кода. Она должна начинаться открытой фигурной скобкой «{». В качестве альтернативы эту открытую скобку можно поместить на новую строку под оператором. Блоки кода – это фрагменты кода, которые выполняют определенные, отдельные задачи.

- Код внутри блока кода должен иметь отступ, чтобы отделить его от остальных.

- Открытые блоки кода должны быть закрыты закрывающей фигурной скобкой «}».

- Комментарии – это строки, которым предшествуют символы «//».

Если вы нажимаете кнопку «запустить» или «скомпилировать» и получаете ошибку, то есть большая вероятность, что вы где-то пропустили точку с запятой!

Вы никогда не перестанете делать это, и это никогда не перестанет вас раздражать. Расслабьтесь!

С этими знаниями мы сможем глубже погрузиться в руководство по Java!

Основы Java: ваша первая программа

Зайдите на compilejava.net, и вас встретит редактор с кучей готовых примеров.

(Если же вы предпочитаете использовать другую IDE или стороннее приложение, это тоже прекрасно! Скорее всего, ваш новый проект будет состоять из аналогичного кода).

Удалите все, кроме следующего:

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

}

}

Это то, что мы, программисты, мы называем «шаблоном» (этот код скопирован из учебника Java от Фила Данфи). Шаблонный код – так можно назвать любой код, который встречается внутри практически любой программы.

Первая строка здесь определяет «класс», который по сути является модулем кода. Затем нам нужен метод внутри этого класса, который представляет собой небольшой блок кода, выполняющий задачу. В каждой программе Java должен быть метод main, так как он сообщает Java, где начинается программа.

Об остальном поговорим чуть ниже, не беспокойтесь. Все, что нам нужно знать для этого урока Java прямо сейчас, – это то, что код, который мы действительно хотим запустить, должен быть помещен в фигурные скобки под словом «main».

Поместите сюда следующий оператор:

System.out.print("Hello world!");

Этот оператор напишет слова: «Hello world!» на вашем экране. Нажмите «Compile & Execute» и вы увидите его в действии.

Поздравляю! Вы только что написали свое первое Java-приложение!

Переменные в Java

Теперь пришло время рассказать о некоторых более важных вещах, лежащих в основе Java. Мало что может быть более фундаментальным в программировании, чем обучение использованию переменных!

Переменная по сути является «контейнером» для некоторых данных. Это означает, что вы выберете слово, которое будет представлять какое-то значение. Нам также необходимо определить переменные, основанные на типе данных, на которые они будут ссылаться.

Вот три основных типа переменных, которые мы собираемся ввести в этом руководстве по Java:

- Целые числа (integers) – как целые числа.

- Плавающие точки (floats) – или «переменные с плавающей точкой». Они содержат все числа, в том числе те, которые представляют десятичные дроби. «Плавающая точка» относится к десятичному разряду.

- Строки (strings)– строки содержат буквенно-цифровые символы и символы. Обычно строка используется для хранения чьего-то имени или, возможно, предложения.

Как только мы определяем переменную, мы можем вставить ее в наш код, чтобы изменить выходные данные. Например:

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

String name = "Adam";

System.out.print("Hello " + name);

}

}

В этом примере кода мы определили строковую переменную с именем name. Мы сделали это, используя тип данных String, за которым следует имя нашей переменной, а затем данные. Когда вы помещаете что-то в двойные кавычки, то Java интерпретирует это дословно как строку.

Теперь мы печатаем на экране, как и раньше, но на этот раз заменяем «Hello world!» на «Hello + имя». Этот код показывает строку «Hello», за которой следует любое значение, содержащееся в следующей строковой переменной!

Самое замечательное в использовании переменных заключается в том, что они позволяют нам манипулировать данными, чтобы наш код мог вести себя динамически. Изменяя значение name, вы можете изменить поведение программы, не изменяя никакого фактического кода!

Условные операторы в Java

Еще одна из самых важных основ Java – это работа с условными операторами.

Условные операторы используют блоки кода, которые выполняются только при определенных условиях. Например, мы можем захотеть предоставить специальные пользовательские права основному пользователю нашего приложения.

Посмотрите на следующий код:

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

String name = "Adam";

System.out.print("Hello " + name +"rn");

if (name == "Adam")

{

System.out.print("Special user priveledges granted!");

}

}

}

Запустите этот код, и вы увидите, что специальные разрешения предоставлены. Но, если вы измените значение name на что-то другое, то код не будет работать.

В этом коде используется оператор if. Он проверяет, является ли утверждение, содержащееся в скобках, истинным. Если это так, то будет запущен следующий блок кода. Не забудьте сделать отступ в коде, а затем закрыть блок в конце! Если оператор в скобках имеет значение false, то код просто пропустит этот раздел и продолжит работу с закрытых скобок.

Обратите внимание, что при наложении условия на данные мы используем два знака «=». Вы же используете только один, когда присваиваете какие-то данные переменным.

Методы на Java

Еще одна простая концепция, которую мы можем ввести в этом руководстве Java – это использование методов. Это даст вам немного больше понимания того, как структурирован Java-код и что с ним можно сделать.

Все, что мы собираемся сделать, – это взять часть кода, который мы уже написали, а затем поместить его в другой метод вне метода main:

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

String name = "Adam";

System.out.print("Hello " + name +"rn");

if (name == "Adam") {

grantPermission();

}

}

static void grantPermission()

{

System.out.print("Special user priveleges granted!");

}

}

Мы создали новый метод в строке, которая начинается со static void. Это означает, что метод определяет функцию, а не свойство объекта, и что он не возвращает никаких данных.

Но все, что мы вставляем в следующий блок кода, теперь будет выполняться каждый раз, когда мы «вызываем» метод, записывая его имя в нашем коде: grantPermission(). Затем программа выполнит этот блок кода и вернется к точке, из которой она вышла.

Если бы мы написали вызов grantPermission() несколько раз, то сообщение «Special user priveleges granted» также отобразилось бы несколько раз. Именно это делает методы такими фундаментальными основами Java: они позволяют выполнять повторяющиеся задачи, не записывая код снова и снова.

Передача аргументов в Java

Но самое замечательное в методах то, что они могут принимать переменные и манипулировать ими. Мы сделаем это, передав переменные в наши методы как «строки». Вот для чего и нужны скобки, следующие за названием метода.

В следующем примере я создал метод, который получает строковую переменную, названную nameCheck. Затем я могу обратиться к nameCheck из этого блока кода, и ее значение будет равно тому, что я поместил в фигурные скобки, когда вызвал метод.

Для этого руководства по Java я передал значение name методу и поместил туда оператор if. Таким образом, мы можем проверять несколько имен подряд, не набирая один и тот же код снова и снова.

Надеюсь, это даст вам представление о том, насколько мощными могут быть методы!

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

String name = "Adam";

System.out.print("Hello " + name +"rn");

checkUser(name);

}

static void checkUser(String nameCheck)

{

if (nameCheck == "Adam")

{

System.out.print("Special user priveledges granted!");

}

}

}

В завершение

Надеюсь, теперь у вас есть хорошее представление о том, как изучать Java. Вы даже можете сами написать какой-нибудь простой код: используя переменные и условные операторы, вы действительно можете заставить Java делать некоторые интересные вещи уже сейчас.

Следующий этап состоит в понимании объектно-ориентированного программирования и классов. Это понимание есть то, что действительно дает Java и подобным языкам их силу, но поначалу может быть немного сложным для осмысления.

Перевод статьи «Java tutorial for beginners: Write a simple app with no previous experience»

Java has been around since the 90s. And despite its massive success in many areas, this cross-platform, object-oriented programming language is often maligned.

Regardless of how people feel about Java, I can tell you from experience is that it is an excellent programming language. After its first appearance back in 1995, it’s still widely-used – and chances are it’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

You can use Java to build servers, create desktop applications, games, mobile applications and more. There are also other JVM (we’ll discuss what that means very soon) languages such as Kotlin, Groovy, Scala, and Clojure that you can use for different purposes.

Java is also cross-platform which means code you write and compile on one platform can run on any other platform that has Java installed on it. We’ll discuss this topic in much more detail later on.

For now, I can tell you that although Java has its fair share of flaws, it also a has a lot to offer.

Table of Contents

- Prerequisites

- How to Write Hello World in Java

- What’s Going On in the Code?

- What is JVM?

- What is JRE and JDK?

- How To Setup Java on Your Computer?

- How To Install a Java IDE on Your Computer?

- How To Create a New Project on IntelliJ IDEA

- How to Work with Variables in Java

- What Are the Rules for Declaring Variables?

- What Are final Variables?

- What are the Primitive Data Types in Java?

- What is Type Conversion or Casting?

- What are Wrapper Classes in Java

- How to Use Operators in Java

- What Are the Arithmetic Operators?

- What Are the Assignment Operators?

- What Are the Relational Operators?

- What Are the Logical Operators?

- What Are the Unary Operators?

- How to Work with Strings in Java

- How to Format a String

- How to Get the Length of a String or Check if It’s Empty or Not

- How to Split and Join Strings

- How to Convert a String to Upper or Lowercase

- How to Compare Two Strings

- How to Replace Characters or Substring in a String

- How to Check If a String Contains a Substring or Not

- What Are the Different Ways of Inputting and Outputting Data?

- How to Use Conditional Statements in Java

- What is a switch-case statement?

- What is Variable Scope in Java?

- What Are Default Values of Variables in Java?

- How to Work with Arrays in Java

- How to Sort an Array

- How to Perform Binary Search on an Array

- How to Fill an Array

- How to Make Copies of an Array

- How to Compare Two Arrays

- How to Use Loops in Java

- For Loop

- For-Each Loop

- While Loop

- Do-While Loop

- How to Work with Array Lists in Java

- How to Add or Remove Multiple Elements

- How to Remove Elements Based on a Condition

- How to Clone and Compare Array Lists

- How To Check if an Element Is Present or the Array List Is Empty

- How to Sort an Array List

- How To Keep Common Elements From Two Array Lists

- How To Perform an Action on All Elements of an Array List

- How To Work With Hash Maps in Java

- How To Put or Replace Multiple Elements in a Hash Map

- How To Check if a Hash Map Contains an Item or if It’s Empty

- How To Perform an Action on All Elements of a Hash Map

- Classes and Objects in Java

- What is a Method?

- What is Method Overloading?

- What are Constructors in Java?

- What Are Access Modifiers in Java?

- What Are the Getter and Setter Methods in Java?

- What is Inheritance in Java?

- How to Override a Method in Java

- Conclusion

Prerequisites

The only re-requisite for this course is familiarity with any other programming language such as Python, JavaScript, and so on.

Although I’ll explain crucial programming concepts in the context of Java, I’ll not explain things like what a variable is in the context of programming in general.

How to Write Hello World in Java

Ideally the first step should’ve been setting up Java on your computer, but I don’t want to bore you with downloading and installing a bunch of software right at the beginning. For this example, you’ll use https://replit.com/ as your platform.

First, head over to https://replit.com/ and create a new account if you don’t already have one. You can use your existing Google/GitHub/Facebook account to login. Once logged in, you’ll land on your home. From there, use the Create button under My Repls to create a new repl.

In the Create a Repl modal, choose Java as Template, set a descriptive Title such as HelloWorld and hit the Create Repl button.

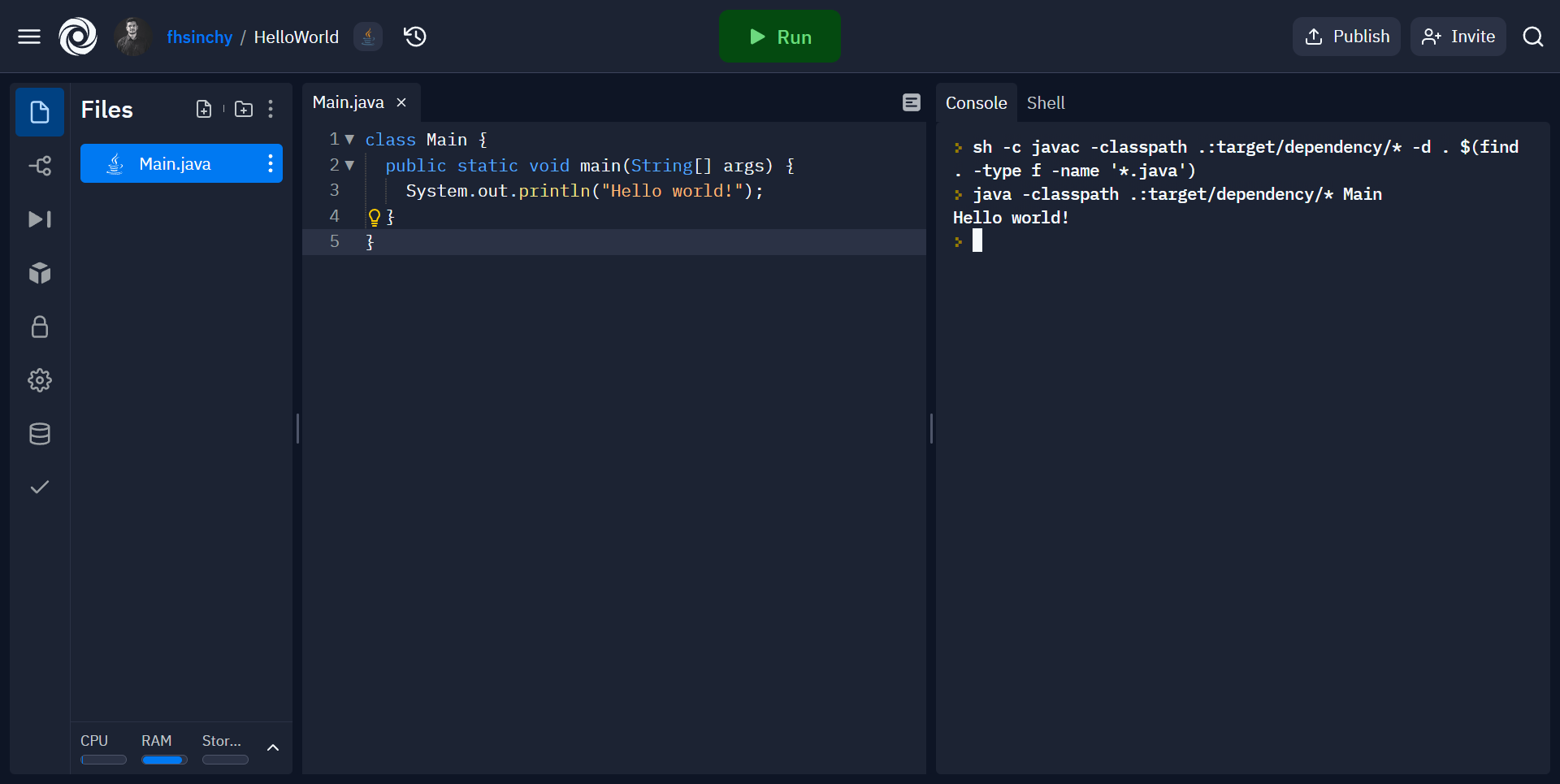

A code editor will show up with an integrated terminal as follows:

On the left side is the list of files in this project, in the middle is the code editor, and on the right side is the terminal.

The template comes with some code by default. You can run the code by hitting the Run button. Go ahead and do that, run the program.

If everything goes fine, you’ll see the words «Hello world!» printed on the right side. Congratulations, you’ve successfully run your first Java program.

What’s Going On in the Code?

The hello world program is probably the most basic executable Java program that you can possibly write – and understanding this program is crucial.

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

}Let’s start with the first line:

class Main {

//...

}This line creates a Main class. A class groups together a bunch of related code within a single unit.

This is a public class, which means this class is accessible anywhere in the codebase. One Java source file (files with the .java extension) can contain only one top level public class in it.

This top level public class has to be named exactly the same as the source code filename. That’s why the file named Main.java contains the main class in this project.

To understand why, click on the three dots in the list of files and click on the Show hidden files option.

This will unveil some new files within the project. Among them is the Main.class file. This is called a bytecode. When you hit the Run button, the Java compiler compiled your code from the Main.java file into this bytecode.

Now, modify the existing Hello World code as follows:

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

}

class NotMain {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Not hello world!");

}

}As you can see, a new class called NotMain has been added. Go ahead and hit the Run button once more while keeping your eyes on the Files menu.

A new bytecode named NotMain.class has showed up. This means that for every class you have within your entire codebase, the compiler will create a separate bytecode.

This creates confusion about which class is the entry-point to this program. To solve this issue, Java uses the class that matches the source code file name as the entry-point to this program.

Enough about the class, now let’s look at the function inside it:

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

}The public static void main (String[] args) function is special in Java. If you have experience with languages like C, C++ or Go, you should already know that every program in those languages has a main function. The execution of the program begins from this main function.

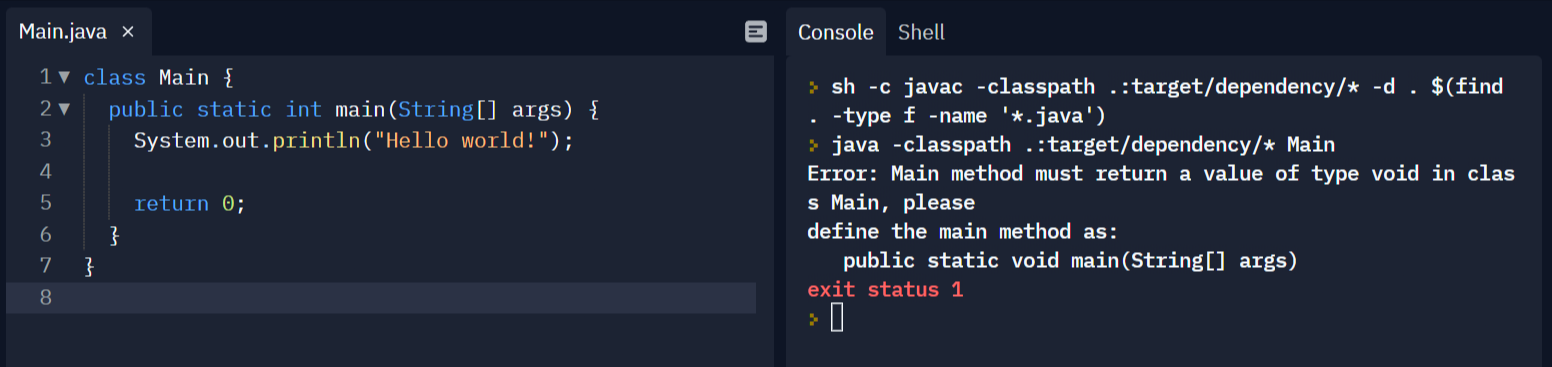

In Java, you have to write this function as exactly public static void main (String[] args) otherwise it won’t work. In fact, if you change it even a little bit Java will start to scream.

The return type has changed from void to int and the function now returns 0 at the end. As you can see in the console, it says:

Error: Main method must return a value of type void in class Main, please

define the main method as:

public static void main(String[] args)Listen to that suggestion and revert your program back to how it was before.

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

}

The main method is a public method and the static means, you can call it without instantiating its class.

The void means that the function doesn’t return any value and the String[] args means that the function takes an array of strings as an argument. This array holds command line arguments passed to the program during execution.

The System.out.println prints out strings on the terminal. In the example above, "Hello world!" has been passed to the function, so you get Hello world! printed on the terminal.

In Java, every statement ends with a semicolon. Unlike JavaScript or Python, semicolons in Java are mandatory. Leaving one out will cause the compilation to fail.

That’s pretty much it for this program. If you didn’t understand every aspect of this section word by word, don’t worry. Things will become much clearer as you go forward.

For now, remember that the top level public class in a Java source file has to match the file name, and the main function of any Java program has to be defined as public static void main(String[] args).

What is JVM?

I’ve uttered the word «bytecode» a few times already in the previous section. I’ve also said that Java is «cross-platform» which means code written and compiled in one platform can run on any platform that has Java installed on it.

You see, your processor doesn’t understand English. In fact the only thing it understands are zeros and ones, aka binary.

When you write and compile a C++ program it results in a binary file. Your processor understands it and based on the program’s targeted platform, this file can be different.

Take an AMD64 and an ARMv8-A processor for example. These processors have different instruction sets. So in order to run your program on these two different platforms, you’ll have to compile them separately.

But a Java program can be written once and run anywhere. I hope you remember the bytecodes we talked about in the previous section. When you compile Java code it doesn’t result in binary but rather in bytecode.

This bytecode is not entirely binary but it’s also not human readable. In fact, your processor can’t read it either.

So instead of throwing this bytecode at the CPU, we instead run it through the Java Virtual Machine or JVM for short. JVM then reads and interprets the bytecode to the CPU.

If you would like to understand the architecture of JVM at a deeper level, I would suggest Siben Nayak’s in-depth article on the topic.

What is JRE and JDK?

JRE stands for Java Runtime Environment and JDK stands for Java Development Kit.

The JRE or Java Runtime Environment packages together an implementation of the JVM along with a set of libraries required for running Java programs.

The JDK, on the other hand, packages the JRE along with all the necessary libraries for developing Java programs.

So if you want to run Java programs on your computer you install the JRE. If you want to develop Java programs yourself, you install the JDK. There are multiple implementation of the JDK.

There is the Java SE (Standard Edition) Development Kit from Oracle, then there is the OpenJDK, an official reference implementation of Java SE (Standard Edition) Development Kit.

As you can tell from the name of OpenJDK, it’s open-source. So there are multiple builds of it. If you’re on a Linux machine and use your distro’s package manager to install JDK, it’s highly likely that you’ll install an OpenJDK build such as Adoptium, Microsoft Build of OpenJDK and so on.

I hope that you understand that JRE is a superset of JVM and JDK is a superset of JRE. Don’t worry about different implementations or builds at the moment, you’ll get your hands on them when the time comes.

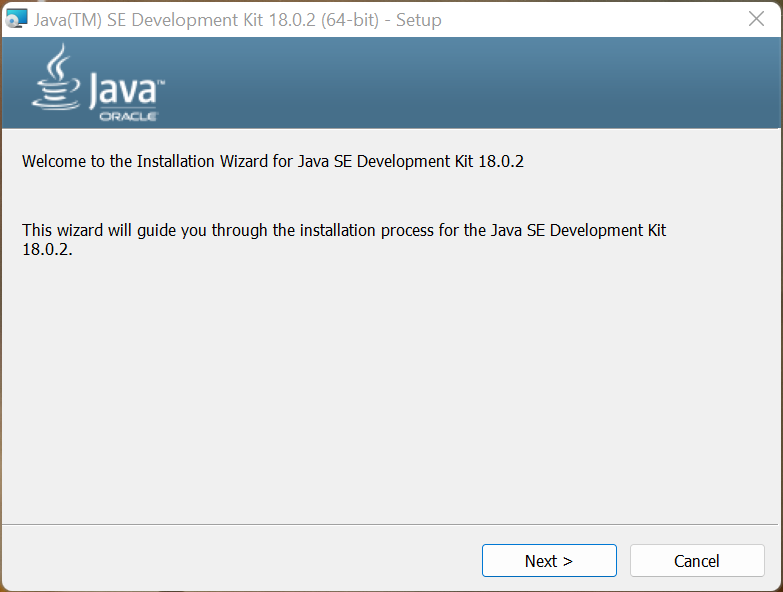

How to Setup Java on Your Computer

First, head over to https://www.oracle.com/java/technologies/downloads/ and download the latest version of the Java SE Development Kit according to the platform you’re on:

Once the download has finished, start the installer and go through the installation process by hitting the Next buttons. Finish it by hitting the Close button on the last page.

The installation process may vary on macOS and Linux but you should be able to figure it out by yourself.

Once the installation has finished, execute the following command on your terminal:

java --version

# java 18.0.2 2022-07-19

# Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 18.0.2+9-61)

# Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 18.0.2+9-61, mixed mode, sharing)If it works, you’ve successfully install Java SE Development Kit on your computer. If you want to use OpenJDK instead, feel free to download Microsoft Build of OpenJDK or Adoptium and go through the installation process.

For the simple example programs that we’re going to write in this article, it won’t matter which JDK you’re using. But in real life, make sure that your JDK version plays nicely with the type of project you’re working on.

How to Install a Java IDE on Your Computer

When it comes to Java, IntelliJ IDEA is undeniably the best IDE out there. Even Google uses it as a base for their Android Studio.

The ultimate version of the IDE can cost an individual up-to $149.00 per year. But if you’re student, you can get educational licenses for all JetBrains products for free.

There is also the completely free and open-source community edition. This is the one we’ll be using throughout the entire book.

Head over to the IntelliJ IDEA download page, and download the community edition for your platform.

Once the download finishes, use the installer to install IntelliJ IDEA like any other software.

How to Create a New Project on IntelliJ IDEA

Use the shortcut from your start menu to start IntelliJ IDEA. The following window will show up:

Use the New Project button and a New Project window will show up:

Put a descriptive name for your project. Leave the rest of the options as they are and press the Create button.

The project creation shouldn’t take longer than a moment and once it’s done, the following window will show up:

That’s the project tool window on the left side. All your source code will live inside that src folder.

Right click on the src folder and go to New > Java Class.

In the next step, put a name, such as Main for your class and make sure Class is highlighted as the type.

A new class will be created with a few lines of code.

Update the code as follows:

public class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello World!");

}

}

To run this code, use the green play button on the right side of the top bar.

The code will run and the output will be shown in the integrated terminal at the bottom of the window.

Congratulations, you’ve successfully recreated the previously discussed HelloWorld program in IntelliJ IDEA.

How to Work with Variables in Java

To work with different kinds of data in Java, you can create variables of different types. For example, if you want to store your age in a new variable, you can do so like this:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// <type> <name>

int age;

}

}

You start by writing out the type of data or variable. Since age is a whole number, its type will be integer or int for short, followed by the name of the variable age and a semicolon.

At the moment, you’ve declared the variable but you haven’t initialized it. In other words, the variable doesn’t have any value. You can initialize the variable as follows:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// <type> <name>

int age;

// <name> = <value>

age = 27;

// prints the age on the terminal

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}When assigning a value, you start by writing the name of the variable you want to initialize, followed by an equal sign (it’s called the assignment operator) then the value you want to assign to the variable. And don’t forget the semicolon at the end.

The System.out.println(); function call will print the line I am 27 years old. to the console. In case you’re wondering, using a plus sign is one of the many ways to dynamically print out variables in the middle of a sentence.

One thing that you have to keep in mind is you can not use an uninitialized variable in Java. So if you comment out the line age = 27 by putting two forward slashes in front of it and try to compile the code, the compiler will throw the following error message at you:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error: Unresolved compilation problem:

The local variable age may not have been initialized

at variables.Main.main(Main.java:13)The line The local variable age may not have been initialized indicates that the variable has not been initialized.

Instead of declaring and initializing the variable in different lines, you can do that in one go as follows:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// <type> <name> = <value>

int age = 27;

// prints the age on the terminal

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}The code should be back to normal again. Also, you can change the value of a variable as many times as you want in your code.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int age = 27;

// updates the value to be 28 instead of 27

age = 28;

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}In this code, the value of age will change from 27 to 28 because you’re overwriting it just before printing.

Keep in mind, while you can assign values to a variables as many times as you want, you can not declare the same variable twice.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// <type> <name> = <value>

int age = 27;

int age = 28;

// prints the age on the terminal

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}If you try to compile this code, the compiler will throw the following error message at you:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error: Unresolved compilation problem:

Duplicate local variable age

at variables.Main.main(Main.java:9)

The line Duplicate local variable age indicates that the variable has already been declared.

Apart from variables, you may find the term «literal» on the internet. Literals are variables with hardcoded values.

For example, here, age = 27 and it’s not dynamically calculated. You’ve written the value directly in the source code. So age is an integer literal.

What Are the Rules for Declaring Variables?

There are some rules when it comes to naming your variables in Java. You can name it anything as long as it doesn’t start with a number and it can’t contain any spaces in the name.

Although, you can start a variable name with an underscore (_) or a dollar sign ($), not being mindful of their usage can make your code hard to read. Variable names are also case sensitive. So age and AGE are two different variables.

Another important thing to remember is you can not use any of the keywords reserved by Java. There are around 50 of them at present. You can learn about these keywords from the official documentation but don’t worry about memorizing them.

As you keep practicing, the important ones will slip into your neurons automatically. And if you still manage to mess up a variable declaration, the compiler will be there to remind you that something’s wrong.

Apart from the rules, there are some conventions that you should follow:

- Start your variable name with small letter and not any special character (like an underscore or dollar sign).

- If the variable name has multiple words, use camel case:

firstName,lastName - Don’t use single letter names:

f,l

As long as you follow these rules and conventions, you’re good to go. If you’d like to learn more about naming conventions in general, checkout my article on the topic.

What Are final Variables?

A final variable in Java can be initialized only once. So if you declare a variable as final, you can not reassign it.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// final <type> <name> = <value>

final int age = 27;

age = 28;

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}Since the age variable has been declared as final, the code will throw the following error message at you:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error: Unresolved compilation problem:

The final local variable age cannot be assigned. It must be blank and not using a compound assignment

at variables.Main.main(Main.java:9)

However, if you leave the variable uninitialized while declaring, the code will work:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// final <type> <name>

final int age;

age = 28;

// prints the age on the terminal

System.out.println("I am " + age + " years old.");

}

}So, declaring a variable as final will limit your ability to reassign its value. If you leave it uninitialized, you’ll be able to initialize it as usual.

What are the Primitive Data Types in Java?

At a high level, there are two types of data in Java. There are the «primitives types» and the «non-primitive» or «reference types».

Primitive types store values. For example, int is a primitive type and it stores an integer value.

A reference type, on the other hand, stores the reference to a memory location where a dynamic object is being stored.

There are eight primitive data types in Java.

| TYPE | EXPLANATION |

|---|---|

byte |

8-bit signed integer within the range of -128 to 127 |

short |

16-bit signed integer within the range of -32,768 to 32,767 |

int |

32-bit signed integer within the range of -2147483648 to 2147483647 |

long |

64-bit signed integer within the range of -9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807 |

float |

single-precision 32-bit floating point within the range of 1.4E-45 to 3.4028235E38 |

double |

double-precision 64-bit floating point within the range of 4.9E-324 to 1.7976931348623157E308 |

boolean |

It can be either true or false |

char |

single 16-bit Unicode character within the range of u0000 (or 0) to uffff (or 65,535 inclusive) |

Yeah yeah I know the table looks scary but don’t stress yourself. You don’t have to memorize them.

You will not need to think about these ranges very frequently, and even if you do, there are ways to print them out within your Java code.

However, if you do not understand what a bit is, I would recommend this short article to learn about binary.

You’ve already learned about declaring an integer in the previous section. You can declare a byte, short, and long in the same way.

Declaring a double also works the same way, except you can assign a number with a decimal point instead of an integer:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double gpa = 4.8;

System.out.println("My GPA is " + gpa + ".");

}

}If you assign an int to the double, such as 4 instead of 4.8, the output will be 4.0 instead of 4, because double will always have a decimal point.

Since double and float are similar, you may think that replacing the double keyword with float will convert this variable to a floating point number – but that’s not correct. You’ll have to append a f or F after the value:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

float gpa = 4.8f;

System.out.println("My GPA is " + gpa + ".");

}

}This happens because, by default, every number with a decimal point is treated as a double in Java. If you do not append the f, the compiler will think you’re trying to assign a double value to a float variable.

boolean data can hold either true or false values.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

boolean isWeekend = false;

System.out.println(isWeekend); // false

}

}As you can imagine, false can be treated as a no and true can be treated as a yes.

Booleans will become much more useful once you’ve learned about conditional statements. So for now, just remember what they are and what they can hold.

The char type can hold any Unicode character within a certain range.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char percentSign = '%';

System.out.println(percentSign); // %

}

}In this example, you’ve saved the percent sign within a char variable and printed it out on the terminal.

You can also use Unicode escape sequences to print out certain symbols.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char copyrightSymbol = 'u00A9';

System.out.println(copyrightSymbol); // ©

}

}The Unicode escape sequence for the copyright symbol, for example, is u00A9 and you can find more Unicode escape sequences on this website.

Among these 8 types of data, you’ll be working with int, double, boolean, and char majority of the time.

What is Type Conversion or Casting?

Type conversion in Java can be either «implicit» or «explicit». When the compiler converts a smaller type of data to a larger one automatically, it’s known as an implicit or narrowing type conversion.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int number1 = 8;

double number2 = number1;

System.out.println(number2); // 8.0

}

}

Since a double is larger than an integer, the compiler could easily perform the conversion. If you try to do the reverse however, you’ll face the following error from the compiler:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error: Unresolved compilation problem:

Type mismatch: cannot convert from double to int

at operators.Main.main(Main.java:7)

When performing an implicit conversion, the flow of conversion should be as follows:

You can of course go from a short to a double, for example, skipping the others in between.

You can also go from smaller data types to larger ones. That’s called an explicit or widening type conversion.

package datatypes;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double number1 = 8.5;

int number2 = (int) number1;

System.out.println(number2); // 8

}

}Previously you’ve seen that if you try to convert a larger data type to a smaller one, the compiler complains. But when you add the (int) cast operator explicitly, you show the compiler who’s boss.

In doing so, you lose a part of your data. If you change the initial double number from 8.5 to just 8.0, you’ll not lose any information. So whenever you’re performing an explicit conversion, be careful.

You can also convert a char to an int as follows:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char character = 'F';

int number = character;

System.out.println(number); // 70

}

}

70 is the ASCII code for the character F – that’s why the output was like this. If you’d like to learn more about ASCII codes, my colleague Kris Koishigawa has written an excellent article on the topic.

The flow of conversion in this case will be the opposite of what you’ve seen already.

I’d suggest you to experiment by converting various values from one type to another and see what happens. This will deepen your understanding and make you confident.

What are Wrapper Classes in Java?

Wrapper classes can wrap around primitive datatypes and turn them into reference types. Wrapper classes are available for all eight primitive data types.

| Primitive Type | Wrapper Class |

|---|---|

int |

Integer |

long |

Long |

short |

Short |

byte |

Byte |

boolean |

Boolean |

char |

Character |

float |

Float |

double |

Double |

You can use these wrapper classes as follows:

public class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Integer age = 27;

Double gpa = 4.8;

System.out.println(age); // 27

System.out.println(gpa); // 4.8

}

}All you have to do is replace the primitive data type with the equivalent wrapper class. These reference types also have methods for extracting the primitive type from them.

For example, age.intValue() will return the age as a primitive integer and the gpa.doubleValue() will return the GPA in a primitive double type.

There are such methods for all eight datatypes. Although you’ll use the primitive types most of the time, these wrapper classes will be handy in some scenarios we’ll discuss in a later section.

How to Use Operators in Java

Operators in programming are certain symbols that tell the compiler to perform certain operations such as arithmetic, relational, or logical operations.

Although there are six types of operators in Java, I won’t talk about bitwise operators here. Discussing bitwise operators in a beginner guide can make it intimidating.

What Are the Arithmetic Operators?

Arithmetic operators are the ones that you can use to perform arithmetic operations. There are five of them:

| OPERATOR | OPERATION |

|---|---|

+ |

Addition |

- |

Subtraction |

* |

Multiplication |

/ |

Division |

% |

Remainder (Modulo/Modulus) |

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division operations are pretty self-explanatory. Have a look at the following code example to understand:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int number1 = 10;

int number2 = 5;

System.out.println(number1 + number2); // 15

System.out.println(number1 - number2); // 5

System.out.println(number1 * number2); // 50

System.out.println(number1 / number2); // 2

System.out.println(number1 % number2); // 0

}

}Outputs from the first four operations need no explanation. In the last operation, you’ve performed a modulo/modulus operation using the % symbol. The result is 0 because if you divide 10 by 2, there’ll be nothing left (no remainder).

Addition and multiplication operations are quite simple. But, when performing a subtraction, if the first operand is larger than the second operand, the result will be a negative number, just like in real life.

The type of data you’re working with makes a difference in the result of division and modulo operations.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int number1 = 8;

int number2 = 5;

System.out.println(number1 / number2); // 1

}

}Although the result of this operation should’ve been 1.6 it didn’t happen because in Java, if you divide an integer by another integer, the result will be an integer. But if you change both or one of them to a float/double, everything will be back to normal.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double number1 = 8;

double number2 = 5;

System.out.println(number1 / number2); // 1.6

}

}

This principle applies to the modulo operations as well. If both or one of the operands are a float/double, the result will be a float/double.