Feeds & Alerts

|

Mailing Lists * |

||||||

|

| Enter the code shown above. |

Board of Directors

Lloyd A. Carney is the Founder and Chief Acquisition Officer of Carney Technology Acquisition Corp II, a Special Purpose Acquisition Corporation, since September 2020. He is the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Carney Global Ventures, LLC, a global investment vehicle, since March 2007. Previously, Mr. Carney served as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of ChaSerg Technology Acquisition Corp, a Special Purpose Acquisition Corp, from September 2018 until March 2020. Before that, he served as CEO and Director of Brocade Communications Systems, Inc., a global supplier of networking hardware and software, from January 2013 to November 2017, following the completion of Brocade’s acquisition by Broadcom Limited. Prior to this role, he was CEO and a Director of Xsigo Systems, an information technology and hardware company, from 2008 to 2012. He also served as CEO and Chairman of the board of Micromuse, Inc., a networking management software company, acquired by IBM, from 2003 to 2006. During his career, Mr. Carney held senior leadership roles at Juniper Networks, Inc., a networking equipment provider, Nortel Networks Inc., a former telecommunications and data networking equipment manufacturer, and Bay Networks, Inc., a computer networking products manufacturer. Mr. Carney serves as the Chairman of the board of directors of Grid Dynamics Holdings, Inc. and also serves on the board of directors of Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Previously, he was a Director of Technicolor S.A. until 2015, and served as Chairman of the board of directors of Nuance Communications, Inc. until March 2022. Mr. Carney holds a B.S. in Electrical Engineering Technology and an Honorary PhD from the Wentworth Institute of Technology, and an M.S. in Applied Business Management from Lesley College.

Kermit R. Crawford served as the President and Chief Operating Officer of Rite Aid Corporation, a retail drugstore chain, from October 2017 to March 2019. Prior to joining Rite Aid, he was the operating partner and advisor with private equity firm Sycamore Partners from July 2015 to February 2017. Mr. Crawford spent the majority of his career at Walgreens Boots Alliance—an integrated healthcare, pharmacy and retail leader with approximately 13,000 global locations—where he worked from 1983 to 2014. He held various positions of increasing responsibility and leadership during his tenure, including the Executive Vice President and President of Pharmacy, Health, and Wellness from April 2011 to December 2014. Mr. Crawford serves on the boards of directors of C.H. Robinson Worldwide and the Allstate Corporation. He previously served on the board of directors of TransUnion until 2021. He is a member of the board of trustees for The Field Museum Chicago. Mr. Crawford holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Pharmacy from Texas Southern University.

Francisco Javier Fernández-Carbajal is the Chief Executive Officer of Servicios Administrativos Contry S.A. de C.V., a privately held company that provides central administrative and investment management services, since June 2005. Prior to this responsibility, Mr. Fernández-Carbajal had an extensive professional career in financial services. From July 2000 to January 2002, he was Chief Executive Officer of the Corporate Development Division of Grupo Financiero BBVA Bancomer, S.A., a Mexico-based banking and financial services company that owns BBVA Bancomer, Mexico’s largest bank. Prior to this role, he held other senior executive positions at Grupo Financiero BBVA Bancomer since joining in September 1991, serving as President from October 1999 to July 2000, and as Chief Financial Officer from October 1995 to October 1999. Mr. Fernández-Carbajal also served as a member of the boards of several of the largest publicly-traded companies in Mexico, operating in diverse manufacturing and service industries, including production and distribution of baked products, grocery and department store retailing, precious metals mining, operation of commercial airports and financial services. Mr. Fernández-Carbajal currently serves on the boards of directors of CEMEX S.A.B. de C.V., a multinational cement and building materials producer and Fomento Económico Mexicano, S.A.B. de C.V., a multinational beverage producer and distributor and convenience store operator. He also serves on the board of directors of ALFA S.A.B. de C.V., a conglomerate involved in petrochemicals, auto parts, packaged foods and telecom, which trades on the BOLSA in Mexico. Mr. Fernández-Carbajal holds a degree in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering from the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

Alfred F. Kelly joined Visa in December 2016 as Chief Executive Officer, was elected Chairman of the board in April 2019 and became Executive Chairman in February 2023. Mr. Kelly spent the majority of his career at American Express where he worked from 1987 to 2010. Over those 23 years, he held several senior positions, including serving as President from July 2007 to April 2010. Immediately prior to Visa, Mr. Kelly was President and Chief Executive Officer at Intersection, a technology and digital media company which is an Alphabet-backed private company based in New York City. Mr. Kelly was a management advisor to TowerBrook Capital Partners, L.P. in 2015, while simultaneously serving as chair of Pope Francis’ visit to New York City. From April 2011 to August 2014, Mr. Kelly was the President and Chief Executive Officer of the 2014 NY/NJ Super Bowl Host Company, the entity created to raise funds for and host Super Bowl XLVIII. Prior to joining American Express, Mr. Kelly was the head of information systems at the White House from 1985 to 1987. Mr. Kelly also held various positions in information systems and financial planning at PepsiCo Inc. from 1981 to 1985. Mr. Kelly currently serves on the board of directors of Visa, the Business Roundtable and Catalyst, as well as several entities in the Archdiocese of New York and is a guardian for the Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican. He is Chairman of the Payments Leadership Council and the Business Roundtable Technology Committee as well as Chairman of the board of the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation. He is also a Trustee of New York Presbyterian Hospital and Boston College. In 2016, Mr. Kelly was named a Knight in the Order of Saint Gregory the Great, by Pope Francis. Mr. Kelly holds a bachelor of arts degree in Computer and Information Science and a masters of business administration degree from Iona University.

-(1).jpg)

Ramon Laguarta has served as Chief Executive Officer and Director of PepsiCo since October 2018, and assumed the role of Chairman of the board in February 2019. Mr. Laguarta previously served as President from 2017 to 2018. Prior to serving as President, Mr. Laguarta held a variety of positions of increasing responsibility in Europe, including as Commercial Vice President of PepsiCo Europe from 2006 to 2008, PepsiCo Eastern Europe Region from 2008 to 2012, President, Developing & Emerging Markets, PepsiCo Europe from 2012 to 2015, Chief Executive Officer, PepsiCo Europe in 2015, and Chief Executive Officer, Europe Sub-Saharan Africa from 2015 until 2017. From 2002 to 2006, he was General Manager for Iberia Snacks and Juices, and from 1999 to 2001 a General Manager for Greece Snacks. Prior to joining PepsiCo in 1996 as a Marketing Vice President for Spain Snacks, Mr. Laguarta worked for Chupa Chups, S.A., where he worked in several international assignments in Europe and the United States. Mr. Laguarta holds an MBA from ESADE Business School in Barcelona, Spain, and a Master’s in International Management from Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University.

-resize.jpg)

Teri L. List was Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of Gap Inc., a global clothing retailer, until her retirement in June 2020. Prior to joining Gap, she served as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of Dick’s Sporting Goods, Inc. and Kraft Foods Group, Inc. Prior to those roles, Ms. List served in various positions of increasing responsibility in the accounting and finance organization of The Procter & Gamble Company, most recently as Senior Vice President and Treasurer. Prior to joining Procter & Gamble, she was employed by the accounting firm of Deloitte & Touche LLP for almost ten years. Ms. List serves on the boards of directors of Danaher Corporation, DoubleVerify Holdings, Inc., and Microsoft Corporation. She previously served on the board of directors of Oscar Health, Inc. until April 2022. Ms. List holds a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Northern Michigan University and is a certified public accountant.

John F. Lundgren is the Lead Independent Director of our board of directors. Mr. Lundgren was Chief Executive Officer of Stanley Black & Decker, Inc. from March 2010 until his retirement in July 2016. He also served as Chairman until December 2016. Previously, Mr. Lundgren served as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of The Stanley Works, a worldwide supplier of consumer products, industrial tools and security solutions for professional, industrial and consumer use, from March 2004 until its merger with Black & Decker in March 2010. Prior to joining The Stanley Works, Mr. Lundgren served as President of European Consumer Products of Georgia-Pacific Corporation from January 2000 to February 2004. Previously, he had held the same position with James River Corporation from 1995 to 1997 and Fort James Corporation from 1997 to 2000 until its acquisition by Georgia-Pacific. Mr. Lundgren serves as Chairman of the board of Topgolf Callaway Brands Corp. He holds a B.A. from Dartmouth College and an MBA from Stanford University.

Ryan McInerney has been with Visa since June of 2013 and serves as chief executive officer. Prior to assuming the role of CEO in February 2023, he was president, responsible for Visa’s global businesses.

Prior to joining Visa, Mr. McInerney served as chief executive officer of consumer banking for JPMorgan Chase, a business with more than 75,000 employees and revenues of approximately $14 billion. Previously, Mr. McInerney served as chief operating officer for home lending and as chief risk officer for Chase’s consumer businesses. He also served as Chase’s head of product and marketing for consumer banking.

Previously, Mr. McInerney was a principal at McKinsey & Company in the firm’s retail banking and payments practices. Mr. McInerney received a Bachelor of Science in finance from the University of Notre Dame.

Denise M. Morrison is the Founder of Denise Morrison & Associates, LLC., a consulting firm. She served as President and Chief Executive Officer of The Campbell Soup Company from 2011 to 2018. She joined Campbell in 2003, where she held positions of increasing responsibility. Prior to joining Campbell, Ms. Morrison held executive management positions at Kraft Foods, Inc. from 2001-2003. She started her career with Procter & Gamble and held various positions with PepsiCo and Nestle before joining Kraft/Nabisco.

Ms. Morrison is currently Director on the boards of Visa Inc., MetLife Inc., and Quest Diagnostics. She served as a Director of Campbell Soup Company from 2010-2018 and a Director of The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. from 2005-2010. She is a member of the Board of Trustees and the Executive Committee for Boston College, and the Advisory Council for Just Capital and is a member of The Business Council. She serves as a sponsor for Bank of America’s Women’s Sponsorship Council and their Enterprise Executive Development Program from 2020 to present.

Ms. Morrison served as a member of Governor Philip Murphy’s NJ Restart & Recovery Commission. She served on President Trump’s Manufacturing Jobs Initiative as well as President Obama’s Export Council. She has been a leader in the Food Industry with a focus on making Real Food affordable and accessible to all families for better health and wellbeing. She has also been an advocate of Healthy Communities starting with Campbell’s headquarter city of Camden, N.J. She was named to Fortune’s Most Powerful Women’s List from 2012-2018.

She has extensive executive experience, including general management, strategic planning, operations, sales and marketing with large multinational corporations operating in consumer focused and regulated industries. Ms. Morrison earned the CERT Certificate in Cybersecurity Oversight, issued by the CERT Division of the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University. She graduated Magna Cum Laude from the University of Boston College in 1975 and received an Honorary Doctorate from St. Peter’s University in 2018.

Pamela Murphy is Chief Executive Officer of Imperva, Inc., a cybersecurity software and services provider, since January 2020. Before assuming her current role, she served as Chief Operating Officer of Infor, Inc., an enterprise software company, from 2011 to the end of 2019, and as Senior Vice President, Corporate Operations from 2010 to 2011. Prior to Infor, Ms. Murphy spent over 10 years at Oracle Corporation, a computer technology corporation, in multiple leadership roles, as Vice President for Global Business Units Finance and Global Sales Operations from 2008 to 2010, as Vice President, Finance from 2007 to 2008, as Director, Consulting Business Operations in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa from 2002 to 2007, and as Senior Manager in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa Finance from 2000 to 2002. Before Oracle, Ms. Murphy worked at Arthur Andersen LLP, accounting firm, as Senior Manager, Business Consulting from 1997 to 2000, and as Auditor from 1995 to 1997. Ms. Murphy serves on the board of directors of Rockwell Automation, Inc. Ms. Murphy earned her Bachelor of Commerce in Accounting and Finance from the University of Cork, Ireland, and is a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland.

Linda J. Rendle has served as Chief Executive Officer and Director of The Clorox Company since September 2020. During nearly 20 years with the company, she has held numerous senior leadership roles. Previously, she served as President from May 2020 to September 2020. Before becoming President, she served as Executive Vice President – Cleaning, International, Strategy and Operations from July 2019 to May 2020, and Executive Vice President – Strategy and Operations from January 2019 to July 2019. Prior to that, she was Executive Vice President and General Manager – Cleaning and Strategy from June 2018 to January 2019, and she served as Senior Vice President and General Manager – Cleaning, from August 2016 to June 2018, with additional responsibility for Professional Products as of April 2017. She served as Vice President and General Manager – Home Care from October 2014 to August 2016. She began her Clorox career in 2003 in the Sales division, where she served in various positions of increasing responsibility in sales planning and supply chain, culminating in her role as Vice President – Sales – Cleaning, from 2012 to 2014. Before joining Clorox, she worked for Procter & Gamble, where she held several positions in sales management. Ms. Rendle holds a bachelor’s degree in economics from Harvard University.

Maynard Webb is the Founder of Webb Investment Network, an early stage venture capital firm he started in 2010. Mr. Webb served as the Chairman of the board of LiveOps Inc., a cloud-based call center, from 2008 to 2013 and was the Chief Executive Officer from 2006 to 2011. Previously, Mr. Webb was the Chief Operating Officer of eBay, Inc., a global commerce and payments provider, from 2002 to 2006, and President of eBay Technologies from 1999 to 2002. Prior to joining eBay, Mr. Webb was Senior Vice President and Chief Information Officer at Gateway, Inc., a computer manufacturer, and Vice President and Chief Information Officer at Bay Networks, Inc., a computer networking products manufacturer. Mr. Webb currently serves as a Director of Salesforce. Mr. Webb served as the Chairman of the board at Yahoo! Inc., until 2017. Mr. Webb holds a Bachelor of Applied Arts degree from Florida Atlantic University.

ООО «Виза» — руководитель:

Бернер Михаил Борисович (ИНН 770302724892).

ИНН 7710759236, ОГРН 1097746706530.

ОКПО 63730389, зарегистрировано 12.11.2009 по юридическому адресу 123056, город Москва, ул Гашека, д. 7 стр. 1, офис 720.

Размер уставного капитала — 92 000 000 рублей. Статус:

действующая с 12.11.2009.

Подробнее >

До Бернер Михаил Борисович,

руководителем «Виза»

являлись:

Петелина Екатерина Владимировна (ИНН 526201870724), Торре Эндрю Энтони .

Ранее ООО «Виза» находилось по адресу:

123056, город Москва, ул. Гашека, д.7 стр. 1, офис 850.

Компания работает

13 лет 6 месяцев,

с 12 ноября 2009

по настоящее время.

В выписке ЕГРЮЛ учредителями указано 2 иностранных юридических лица. Основной вид деятельности «Виза» — Консультирование по вопросам коммерческой деятельности и управления и 6 дополнительных видов.

Состоит на учете в налоговом органе Инспекция ФНС России № 10 по г. Москве с 12 ноября 2009 г., присвоен КПП 771001001.

Регистрационный номер

ПФР 087103061184, ФСС 770402877077041.

< Свернуть

Искали другую одноименную компанию? Смотрите полный перечень юридических лиц с названием ООО «Виза».

Компания ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ «ВИЗА» зарегистрирована 12.11.2009 г.

Краткое наименование: ВИЗА.

При регистрации организации присвоен ОГРН 1097746706530, ИНН 7710759236 и КПП 771001001.

Юридический адрес: Г.Москва МУНИЦИПАЛЬНЫЙ ОКРУГ ПРЕСНЕНСКИЙ РАЙОН УЛ ГАШЕКА 7 СТРОЕНИЕ 1 ОФИС 720.

Бернер Михаил Борисович является генеральным директором организации.

Учредители компании — ВИЗА ИНТЕРНЭШНЛ СЕРВИС АССОСИЭЙШЕН НЕАКЦИОНЕРНАЯ КОРПОРАЦИЯ, ВИЗА ИНТЕРНЭШНЛ ХОЛДИНГС ЛЛС, КОМПАНИЯ С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ.

Среднесписочная численность (ССЧ) работников организации — 102.

В соответствии с данными ЕГРЮЛ, основной вид деятельности компании ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ «ВИЗА» по ОКВЭД: 63.11 Деятельность по обработке данных, предоставление услуг по размещению информации и связанная с этим деятельность.

Общее количество направлений деятельности — 7.

За 2021 год прибыль компании составляет — 894 405 000 ₽, выручка за 2021 год — 21 590 550 000 ₽.

Размер уставного капитала ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ «ВИЗА» — 92 000 000,00 ₽.

Выручка на начало 2021 года составила 18 625 888 000 ₽, на конец — 21 590 550 000 ₽.

Себестоимость продаж за 2021 год — 19 800 757 000 ₽.

Валовая прибыль на конец 2021 года — 1 789 793 000 ₽.

Общая сумма поступлений от текущих операций на 2021 год — 21 056 035 000 ₽.

На 21 мая 2023 организация действует.

Юридический адрес ВИЗА, выписка ЕГРЮЛ, аналитические данные и бухгалтерская отчетность организации доступны в системе.

«VISA» redirects here. For the document needed to enter a country’s territory, see Travel visa. For other uses, see Visa (disambiguation).

|

|

Headquarters at Metro Center in Foster City, California |

|

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

|

Traded as |

|

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | September 18, 1958; 64 years ago (as BankAmericard in Fresno, California, U.S.) |

| Founder | Dee Hock |

| Headquarters | One Market Plaza, San Francisco, California, U.S.[1] |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

c. 26,500 (2022) |

| Website | visa.com |

| Footnotes / references Financials as of September 30, 2022. References:[3] |

Visa Inc. (; stylized as VISA) is an American multinational financial services corporation headquartered in San Francisco, California.[1][4] It facilitates electronic funds transfers throughout the world, most commonly through Visa-branded credit cards, debit cards and prepaid cards.[5] Visa is one of the world’s most valuable companies.

Visa does not issue cards, extend credit or set rates and fees for consumers; rather, Visa provides financial institutions with Visa-branded payment products that they then use to offer credit, debit, prepaid and cash access programs to their customers. In 2015, the Nilson Report, a publication that tracks the credit card industry, found that Visa’s global network (known as VisaNet) processed 100 billion transactions during 2014 with a total volume of US$6.8 trillion.[6]

Visa was founded in 1958 by Bank of America (BofA) as the BankAmericard credit card program.[7] In response to competitor Master Charge (now Mastercard), BofA began to license the BankAmericard program to other financial institutions in 1966.[8] By 1970, BofA gave up direct control of the BankAmericard program, forming a cooperative with the other various BankAmericard issuer banks to take over its management. It was then renamed Visa in 1976.[9]

Nearly all Visa transactions worldwide are processed through the company’s directly operated VisaNet at one of four secure data centers, located in Ashburn, Virginia; Highlands Ranch, Colorado; London, England; and Singapore.[10] These facilities are heavily secured against natural disasters, crime, and terrorism; can operate independently of each other and from external utilities if necessary; and can handle up to 30,000 simultaneous transactions and up to 100 billion computations every second.[6][11][12]

Visa is the world’s second-largest card payment organization (debit and credit cards combined), after being surpassed by China UnionPay in 2015, based on annual value of card payments transacted and number of issued cards. However, because UnionPay’s size is based primarily on the size of its domestic market in China, Visa is still considered the dominant bankcard company in the rest of the world, where it commands a 50% market share of total card payments.

History[edit]

Old «Your BankAmericard Welcome Here» sign

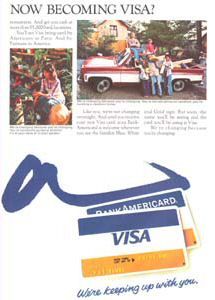

A 1976 ad promoting the change of name to «Visa». Note the early Visa card shown in the ad, as well as the image of the BankAmericard that it replaced.

On September 18, 1958, Bank of America (BofA) officially launched its BankAmericard credit card program in Fresno, California.[7] In the weeks leading up to the launch of BankAmericard, BofA had saturated Fresno mailboxes with an initial mass mailing (or «drop», as they came to be called) of 65,000 unsolicited credit cards.[7][14] BankAmericard was the brainchild of BofA’s in-house product development think tank, the Customer Services Research Group, and its leader, Joseph P. Williams. Williams convinced senior BofA executives in 1956 to let him pursue what became the world’s first successful mass mailing of unsolicited credit cards (actual working cards, not mere applications) to a large population.[15]

Williams’ pioneering accomplishment was that he brought about the successful implementation of the all-purpose credit card (in the sense that his project was not canceled outright), not in coming up with the idea.[15] By the mid-1950s, the typical middle-class American already maintained revolving credit accounts with several different merchants, which was clearly inefficient and inconvenient due to the need to carry so many cards and pay so many separate bills each month.[16] The need for a unified financial instrument was already evident to the American financial services industry, but no one could figure out how to do it. There were already charge cards like Diners Club (which had to be paid in full at the end of each billing cycle), and «by the mid-1950s, there had been at least a dozen attempts to create an all-purpose credit card.»[16] However, these prior attempts had been carried out by small banks which lacked the resources to make them work.[16] Williams and his team studied these failures carefully and believed they could avoid replicating those banks’ mistakes; they also studied existing revolving credit operations at Sears and Mobil Oil to learn why they were successful.[16] Fresno was selected for its population of 250,000 (big enough to make a credit card work, small enough to control initial startup cost), BofA’s market share of that population (45%), and relative isolation, to control public relations damage in case the project failed.[17] According to Williams, Florsheim Shoes was the first major retail chain which agreed to accept BankAmericard at its stores.[18]

Visa logo used from July 1, 1992 to 2000

Visa logo used from August 1998 to 2005

Visa logo used from late 2005 to January 2014

Visa logo used from January 2014 to July 2021

Visa logo used since July 2021

Visa acceptance logo from early 2015 (used only in certain Asian, American and European markets)

The 1958 test at first went smoothly, but then BofA panicked when it confirmed rumors that another bank was about to initiate its own drop in San Francisco, BofA’s home market.[19] By March 1959, drops began in San Francisco and Sacramento; by June, BofA was dropping cards in Los Angeles; by October, the entire state of California had been saturated with over 2 million credit cards and BankAmericard was being accepted by 20,000 merchants.[19] However, the program was riddled with problems, as Williams (who had never worked in a bank’s loan department) had been too earnest and trusting in his belief in the basic goodness of the bank’s customers, and he resigned in December 1959. Twenty-two percent of accounts were delinquent, not the 4% expected, and police departments around the state were confronted by numerous incidents of the brand new crime of credit card fraud.[20] Both politicians and journalists joined the general uproar against Bank of America and its newfangled credit card, especially when it was pointed out that the cardholder agreement held customers liable for all charges, even those resulting from fraud.[21] BofA officially lost over $8.8 million on the launch of BankAmericard, but when the full cost of advertising and overhead was included, the bank’s actual loss was probably around $20 million.[21]

However, after Williams and some of his closest associates left, BofA management realized that BankAmericard was salvageable.[22] They conducted a «massive effort» to clean up after Williams, imposed proper financial controls, published an open letter to 3 million households across the state apologizing for the credit card fraud and other issues their card raised and eventually were able to make the new financial instrument work.[22] By May 1961, the BankAmericard program became profitable for the first time.[23] At the time, BofA deliberately kept this information secret and allowed then-widespread negative impressions to linger in order to ward off competition.[24] This strategy worked until 1966, when BankAmericard’s profitability had become far too big to hide.[24]

The original goal of BofA was to offer the BankAmericard product across California, but in 1966, BofA began to sign licensing agreements with a group of banks outside of California, in response to a new competitor, Master Charge (now MasterCard), which had been created by an alliance of several regional bankcard associations to compete against BankAmericard. BofA itself (like all other U.S. banks at the time) could not expand directly into other states due to federal restrictions not repealed until 1994. Over the following 11 years, various banks licensed the card system from Bank of America, thus forming a network of banks backing the BankAmericard system across the United States.[8] The «drops» of unsolicited credit cards continued unabated, thanks to BofA and its licensees and competitors until they were outlawed in 1970,[25] but not before over 100 million credit cards had been distributed into the American population.[26]

During the late 1960s, BofA also licensed the BankAmericard program to banks in several other countries, which began issuing cards with localized brand names. For example:[citation needed]

- In Canada, an alliance of banks (including Toronto-Dominion Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Royal Bank of Canada, Banque Canadienne Nationale and Bank of Nova Scotia) issued credit cards under the Chargex name from 1968 to 1977.

- In France, it was known as Carte Bleue (Blue Card). The logo still appears on many French-issued Visa cards today.

- In Japan, The Sumitomo Bank issued BankAmericards through the Sumitomo Credit Service.

- In the UK, the only BankAmericard issuer for some years was Barclaycard. The branding still exists today, but is used not only on Visa cards issued by Barclays, but on its MasterCard and American Express cards as well.[27]

- In Spain until 1979 the only issuer was Banco de Bilbao.

In 1968, a manager at the National Bank of Commerce (later Rainier Bancorp), Dee Hock, was asked to supervise that bank’s launch of its own licensed version of BankAmericard in the Pacific Northwest market. Although Bank of America had cultivated the public image that BankAmericard’s troubled startup issues were now safely in the past, Hock realized that the BankAmericard licensee program itself was in terrible disarray because it had developed and grown very rapidly in an ad hoc fashion. For example, «interchange» transaction issues between banks were becoming a very serious problem, which had not been seen before when Bank of America was the sole issuer of BankAmericards. Hock suggested to other licensees that they form a committee to investigate and analyze the various problems with the licensee program; they promptly made him the chair of that committee.[28]

After lengthy negotiations, the committee led by Hock was able to persuade Bank of America that a bright future lay ahead for BankAmericard — outside Bank of America. In June 1970, Bank of America gave up control of the BankAmericard program. The various BankAmericard issuer banks took control of the program, creating National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI), an independent Delaware corporation which would be in charge of managing, promoting and developing the BankAmericard system within the United States. In other words, BankAmericard was transformed from a franchising system into a jointly controlled consortium or alliance, like its competitor Master Charge. Hock became NBI’s first president and CEO.[29]

However, Bank of America retained the right to directly license BankAmericard to banks outside the United States and continued to issue and support such licenses. By 1972, licenses had been granted in 15 countries. The international licensees soon encountered a variety of problems with their licensing programs, and they hired Hock as a consultant to help them restructure their relationship with BofA as he had done for the domestic licensees. As a result, in 1974, the International Bankcard Company (IBANCO), a multinational member corporation, was founded in order to manage the international BankAmericard program.[30]

In 1976, the directors of IBANCO determined that bringing the various international networks together into a single network with a single name internationally would be in the best interests of the corporation; however, in many countries, there was still great reluctance to issue a card associated with Bank of America, even though the association was entirely nominal in nature. For this reason, in 1976, BankAmericard, Barclaycard, Carte Bleue, Chargex, Sumitomo Card, and all other licensees united under the new name, «Visa«, which retained the distinctive blue, white and gold flag. NBI became Visa USA and IBANCO became Visa International.[9]

The term Visa was conceived by the company’s founder, Dee Hock. He believed that the word was instantly recognizable in many languages in many countries and that it also denoted universal acceptance.[31]

The announcement of the transition came on December 16, 1976, with VISA cards to replace expiring BankAmericard cards starting on March 1, 1977 (initially with both the BankAmericard name and the VISA name on the same card), and the various Bank of America issued cards worldwide being phased out by the end of October 1979. [32]

In October 2007, Bank of America announced it was resurrecting the BankAmericard brand name as the «BankAmericard Rewards Visa».[33]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, in March 2022, Visa announced that it would suspend all business operations in Russia.[34]

Corporate structure[edit]

Prior to October 3, 2007, Visa comprised four non-stock, separately incorporated companies that employed 6,000 people worldwide: the worldwide parent entity Visa International Service Association (Visa), Visa USA Inc., Visa Canada Association, and Visa Europe Ltd. The latter three separately incorporated regions had the status of group members of Visa International Service Association.[citation needed]

The unincorporated regions Visa Latin America (LAC), Visa Asia Pacific and Visa Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa (CEMEA) were divisions within Visa.[citation needed]

Billing and finance charge methods[edit]

Initially, signed copies of sales drafts were included in each customer’s monthly billing statement for verification purposes—an industry practice known as «country club billing»[citation needed]. By the late 1970s, however, billing statements no longer contained these enclosures, but rather a summary statement showing posting date, purchase date, reference number, merchant name, and the dollar amount of each purchase.[citation needed] At the same time, many issuers, particularly Bank of America, were in the process of changing their methods of finance charge calculation. Initially, a «previous balance» method was used—calculation of finance charge on the unpaid balance shown on the prior month’s statement. Later, it was decided to use «average daily balance» which resulted in increased revenue for the issuers by calculating the number of days each purchase was included on the prior month’s statement. Several years later, «new average daily balance»—in which transactions from previous and current billing cycles were used in the calculation—was introduced. By the early 1980s, many issuers introduced the concept of the annual fee as yet another revenue enhancer.[citation needed]

IPO and restructuring[edit]

On October 11, 2006, Visa announced that some of its businesses would be merged and become a publicly traded company, Visa Inc.[35][36][37]

Under the IPO restructuring, Visa Canada, Visa International, and Visa USA were merged into the new public company. Visa’s Western Europe operation became a separate company, owned by its member banks who will also have a minority stake in Visa Inc.[38] In total, more than 35 investment banks participated in the deal in several capacities, most notably as underwriters.

On October 3, 2007, Visa completed its corporate restructuring with the formation of Visa Inc. The new company was the first step towards Visa’s IPO.[39] The second step came on November 9, 2007, when the new Visa Inc. submitted its $10 billion IPO filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[40] On February 25, 2008, Visa announced it would go ahead with an IPO of half its shares.[41] The IPO took place on March 18, 2008. Visa sold 406 million shares at US$44 per share ($2 above the high end of the expected $37–42 pricing range), raising US$17.9 billion in what was then the largest initial public offering in U.S. history.[42] On March 20, 2008, the IPO underwriters (including JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs & Co., Bank of America Securities LLC, Citi, HSBC, Merrill Lynch & Co., UBS Investment Bank and Wachovia Securities) exercised their overallotment option, purchasing an additional 40.6 million shares, bringing Visa’s total IPO share count to 446.6 million, and bringing the total proceeds to US$19.1 billion.[43] Visa now trades under the ticker symbol «V» on the New York Stock Exchange.[44]

Visa Europe[edit]

Visa Europe Ltd. was a membership association and cooperative of over 3,700 European banks and other payment service providers[45] that operated Visa branded products and services within Europe. Visa Europe was a company entirely separate from Visa Inc. having gained independence of Visa International Service Association in October 2007 when Visa Inc. became a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange.[46] Visa Inc. announced the plan to acquire Visa Europe on November 2, 2015, creating a single global company.[47] On April 21, 2016, the agreement was amended in response to the feedback of European Commission.[48] The acquisition of Visa Europe was completed on June 21, 2016.[49]

Failed acquisition of Plaid[edit]

On January 13, 2020, Plaid announced that it had signed a definitive agreement to be acquired by Visa for $5.3 billion.[50][51] The deal was double the company’s most recent Series C round valuation of $2.65 billion,[52] and was expected to close in the next 3–6 months, subject to regulatory review and closing conditions. According to the deal, Visa would pay $4.9 billion in cash and approximately $400 million of retention equity and deferred equity,[53] according to a presentation deck prepared by Visa.[54]

On November 5, 2020, the United States Department of Justice filed a lawsuit seeking to block the acquisition, arguing that Visa is a monopolist trying to eliminate a competitive threat by purchasing Plaid. Visa said it disagrees with the lawsuit and «intends to defend the transaction vigorously.»[55][56]

Digital currencies[edit]

On February 3, 2021, Visa announced a partnership with First Boulevard, a neobank promoting cryptocurrency, which has been touted as a means of building generational wealth for Black Americans.[57] The partnership would allow their users to buy, sell, hold, and trade digital assets through Anchorage Digital.[58][59]

On March 29, 2021, Visa announced the acceptance of stable coin USDC to settle transactions on its network.[60]

On December 19, 2022, Visa shared plans for auto-payments on StarkNet, a Layer 2 scaling solution for Ethereum.[61] Visa’s proposed solution would enable people to pay recurring bills while maintaining custody of their assets, a core tenet of DeFi.[62]

Visa Foundation[edit]

Registered in the United States as a 501(c)(3) entity, the Visa Foundation was created with the mission of supporting inclusive economies. In particular, economies in which individuals, businesses and communities can thrive with the support of grants and investments. Supporting resiliency, as well as the growth, of micro and small businesses that benefit women is a priority of the Visa Foundation. Furthermore, the Foundation prioritizes providing support to the community from a broad standpoint, as well as responding to disasters during crisis.[63]

Other initiatives[edit]

In December 2020, Visa Announced the launch of a new accelerator program across Asia Pacific to further develop the region’s financial technology ecosystem.[64] The accelerator program aims to find and partner with startup companies providing financial and payments technologies that could potentially leverage on Visa’s network of bank and merchant partners in the region.[65]

Finance[edit]

For the fiscal year 2022, Visa reported earnings of US$14.96 billion, with an annual revenue of US$29.31 billion, an increase of 21.6% over the previous fiscal cycle. As of 2022, the company ranked 147th on the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue.[66] Visa’s shares traded at over $143 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at over US$280.2 billion in September 2018.

| Year | Revenue in million US$ |

Net income in million US$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005[67] | 2,665 | 360 | |

| 2006[67] | 2,948 | 455 | |

| 2007[67] | 3,590 | −1,076 | 5,479 |

| 2008[67] | 6,263 | 804 | 5,765 |

| 2009[68] | 6,911 | 2,353 | 5,700 |

| 2010[69] | 8,065 | 2,966 | 6,800 |

| 2011[70] | 9,188 | 3,650 | 7,500 |

| 2012[71] | 10,421 | 2,144 | 8,500 |

| 2013[72] | 11,778 | 4,980 | 9,600 |

| 2014[73] | 12,702 | 5,438 | 9,500 |

| 2015[74] | 13,880 | 6,328 | 11,300 |

| 2016[75] | 15,082 | 5,991 | 11,300 |

| 2017[76] | 18,358 | 6,699 | 12,400 |

| 2018[77] | 20,609 | 10,301 | 15,000 |

| 2019[78] | 22,977 | 12,080 | 19,500 |

| 2020[78] | 21,846 | 10,866 | 20,500 |

| 2021[79] | 24,105 | 12,311 | 21,500 |

| 2022[3] | 29,310 | 14,957 | 26,500 |

Criticism and controversy[edit]

WikiLeaks[edit]

Visa Europe began suspending payments to WikiLeaks on December 7, 2010.[80] The company said it was awaiting an investigation into ‘the nature of its business and whether it contravenes Visa operating rules’ – though it did not go into details.[81] In return DataCell, the IT company that enables WikiLeaks to accept credit and debit card donations, announced that it would take legal action against Visa Europe.[82] On December 8, the group Anonymous performed a DDoS attack on visa.com,[83] bringing the site down.[84] Although the Norway-based financial services company Teller AS, which Visa ordered to look into WikiLeaks and its fundraising body, the Sunshine Press, found no proof of any wrongdoing, Salon reported in January 2011 that Visa Europe «would continue blocking donations to the secret-spilling site until it completes its own investigation».[81]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated that Visa may be «violating WikiLeaks’ right to freedom of expression» by withdrawing their services.[85]

In July 2012, the Reykjavík District Court decided that Valitor (the Icelandic partner of Visa and MasterCard) was violating the law when it prevented donations to the site by credit card. It was ruled that the donations be allowed to return to the site within 14 days or they would be fined in the amount of US$6,000 per day.[86]

Litigation and regulatory actions[edit]

Anti-competitive conduct in Australia[edit]

In 2015, the Australian Federal Court ordered Visa to pay a pecuniary penalty of $20 million (including legal fees) for engaging in anti-competitive conduct against dynamic currency conversion operators, in proceedings brought by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.[87]

Antitrust lawsuit by ATM operators[edit]

In 2011, MasterCard and Visa were sued in a class action by ATM operators claiming the credit card networks’ rules effectively fix ATM access fees.[88] The suit claimed that this is a restraint on trade in violation of US federal law. The lawsuit was filed by the National ATM Council and independent operators of automated teller machines. More specifically, it is alleged that MasterCard’s and Visa’s network rules prohibit ATM operators from offering lower prices for transactions over PIN-debit networks that are not affiliated with Visa or MasterCard. The suit says that this price-fixing artificially raises the price that consumers pay using ATMs, limits the revenue that ATM-operators earn, and violates the Sherman Act’s prohibition against unreasonable restraints of trade.

Johnathan Rubin, an attorney for the plaintiffs said, «Visa and MasterCard are the ringleaders, organizers, and enforcers of a conspiracy among U.S. banks to fix the price of ATM access fees in order to keep the competition at bay.»[89]

In 2017, a US district court denied the ATM operators’ request to stop Visa from enforcing the ATM fees.[90]

Debit card swipe fees[edit]

In 1996, a class of U.S. merchants, including Walmart, brought an antitrust lawsuit against Visa and MasterCard over their «Honor All Cards» policy, which forced merchants who accepted Visa and MasterCard branded credit cards to also accept their respective debit cards (such as the «Visa Check Card»). Over 4 million class members were represented by the plaintiffs. According to a website associated with the suit,[91] Visa and MasterCard settled the plaintiffs’ claims in 2003 for a total of $3.05 billion. Visa’s share of this settlement is reported to have been the larger.

U.S. Justice Department actions[edit]

In 1998, the Department of Justice sued Visa over rules prohibiting its issuing banks from doing business with American Express and Discover. The Department of Justice won its case at trial in 2001 and the verdict was upheld on appeal. American Express and Discover filed suit as well.[92]

In October 2010, Visa and MasterCard reached a settlement with the U.S. Justice Department in another antitrust case. The companies agreed to allow merchants displaying their logos to decline certain types of cards (because interchange fees differ), or to offer consumers discounts for using cheaper cards.[93]

Antitrust issues in Europe[edit]

In 2002, the European Commission exempted Visa’s multilateral interchange fees from Article 81 of the EC Treaty that prohibits anti-competitive arrangements.[94] However, this exemption expired on December 31, 2007. In the United Kingdom, Mastercard has reduced its interchange fees while it is under investigation by the Office of Fair Trading.

In January 2007, the European Commission issued the results of a two-year inquiry into the retail banking sector. The report focuses on payment cards and interchange fees. Upon publishing the report, Commissioner Neelie Kroes said the «present level of interchange fees in many of the schemes we have examined does not seem justified.» The report called for further study of the issue.[95]

On March 26, 2008, the European Commission opened an investigation into Visa’s multilateral interchange fees for cross-border transactions within the EEA as well as into the «Honor All Cards» rule (under which merchants are required to accept all valid Visa-branded cards).[96][needs update]

The antitrust authorities of EU member states (other than the United Kingdom) also investigated Mastercard’s and Visa’s interchange fees. For example, on January 4, 2007, the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection fined twenty banks a total of PLN 164 million (about $56 million) for jointly setting Mastercard’s and Visa’s interchange fees.[97][98]

In December 2010, Visa reached a settlement with the European Union in yet another antitrust case, promising to reduce debit card payments to 0.2 percent of a purchase.[99] A senior official from the European Central Bank called for a break-up of the Visa/Mastercard duopoly by creation of a new European debit card for use in the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA).[100] After Visa’s blocking of payments to WikiLeaks, members of the European Parliament expressed concern that payments from European citizens to a European corporation could apparently be blocked by the US, and called for a further reduction in the dominance of Visa and Mastercard in the European payment system.[101]

Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant Discount Antitrust Litigation[edit]

On November 27, 2012, a federal judge entered an order granting preliminary approval to a proposed settlement to a class-action lawsuit[102] filed in 2005 by merchants and trade associations against Mastercard and Visa. The suit was filed due to alleged price-fixing practices employed by Mastercard and Visa. About one-quarter of the named class plaintiffs have decided to opt «out of the settlement». Opponents object to provisions that would bar future lawsuits and even prevent merchants from opting out of significant portions of the proposed settlement.[103]

Plaintiffs allege that Visa and Mastercard fixed interchange fees, also known as swipe fees, that are charged to merchants for the privilege of accepting payment cards. In their complaint, the plaintiffs also alleged that the defendants unfairly interfere with merchants from encouraging customers to use less expensive forms of payment such as lower-cost cards, cash, and checks.[103]

A settlement of US$6.24 billion has been reached and a court is scheduled to approve or deny the agreement on November 7, 2019.[104]

High swipe fees in Poland[edit]

Very high interchange fee for Visa (1.5–1.6% from every transaction’s final price, which also includes VAT) in Poland started discussion about legality and need for government regulations of interchange fees to avoid high costs for business (which also block electronic payment market and acceptability of cards).[105] This situation also led to the birth of new methods of payment in the year 2013, which avoid the need for go-between (middleman) companies like Visa or Mastercard, for example mobile application issued by major banks,[106] and system by big chain of discount shops,[107] or older public transport tickets buying systems.[108]

Confrontation with Walmart over high fees[edit]

In June 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that Walmart threatened to stop accepting Visa cards in Canada. Visa objected saying that consumers should not be dragged into a dispute between the companies.[109] In January 2017, Walmart Canada and Visa reached a deal to allow the continued acceptance of Visa.[110]

Dispute with Kroger over high credit card fees[edit]

In March 2019, U.S. retailer Kroger announced that its 250-strong Smith’s chain would stop accepting Visa credit cards as of April 3, 2019, due to the cards’ high ‘swipe’ fees. Kroger’s California-based Foods Co stores stopped accepting Visa cards in August 2018. Mike Schlotman, Kroger’s executive vice president/chief financial officer, said Visa had been “misusing its position and charging retailers excessive fees for a long time.” In response, Visa issued a statement saying it was “unfair and disappointing that Kroger is putting shoppers in the middle of a business dispute.”[111] As of October 31, 2019, Kroger has settled their dispute with Visa and is now accepting the payment method.[112]

Antitrust investigation over debit card practices[edit]

In March 2021, the United States Justice Department announced its investigation with Visa to discover if the company is engaging in anticompetitive practices in the debit card market. The main question at hand is whether or not Visa is limiting merchants’ ability to route debit card transactions over card networks that are often less expensive, focusing more so on online debit card transactions. The probe highlights the role of network fees, which are invisible to consumers and place pressure on merchants, who mitigate the fees by raising prices of goods for customers. The probe was confirmed through a regulatory filing on March 19, 2021, stating they will be cooperating with the Justice Department. Visa’s shares fell more than 6% following the announcement.[113][114][115][116]

Corporate affairs[edit]

Headquarters[edit]

In 2009, Visa moved its corporate headquarters back to San Francisco when it leased the top three floors of the 595 Market Street office building, although most of its employees remained at its Foster City campus.[117] In 2012, Visa decided to consolidate its headquarters in Foster City where 3,100 of its 7,700 global workers are employed.[118] Visa owns four buildings at the intersection of Metro Center Boulevard and Vintage Park Drive.

As of October 1, 2012, Visa’s headquarters are located in Foster City, California.[118] Visa had been headquartered in San Francisco until 1985, when it moved to San Mateo.[119] Around 1993, Visa began consolidating various scattered offices in San Mateo to a location in Foster City.[119] Visa became Foster City’s largest employer.

In December 2012, Visa Inc. confirmed that it will build a global information technology center off of the US 183 Expressway in northwest Austin, Texas.[120] By 2019, Visa leased space in four buildings near Austin and employed nearly 2,000 people.[121]

On November 6, 2019, Visa announced plans to move its headquarters back to San Francisco by 2024 upon completion of a new «13-story, 300,000-square-foot building».[122]

Operations[edit]

Visa offers through its issuing members the following types of cards:

- Debit cards (pay from a checking/savings account)

- Credit cards (pay monthly payments with or without interest depending on a customer paying on time)

- Prepaid cards (pay from a cash account that has no check writing privileges)

Visa operates the Plus automated teller machine network and the Interlink EFTPOS point-of-sale network, which facilitate the «debit» protocol used with debit cards and prepaid cards. They also provide commercial payment solutions for small businesses, midsize and large corporations, and governments.[123]

Visa teamed with Apple in September 2014, to incorporate a new mobile wallet feature into Apple’s new iPhone models, enabling users to more readily use their Visa, and other credit/debit cards.[124]

Operating regulations[edit]

Visa has a set of rules that govern the participation of financial institutions in its payment system. Acquiring banks are responsible for ensuring that their merchants comply with the rules.

Rules address how a cardholder must be identified for security, how transactions may be denied by the bank, and how banks may cooperate for fraud prevention, and how to keep that identification and fraud protection standard and non-discriminatory. Other rules govern what creates an enforceable proof of authorization by the cardholder.[125]

The rules prohibit merchants from imposing a minimum or maximum purchase amount in order to accept a Visa card and from charging cardholders a fee for using a Visa card.[125] In ten U.S. states, surcharges for the use of a credit card are forbidden by law (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Oklahoma and Texas) but a discount for cash is permitted under specific rules.[126] Some countries have banned the no-surcharge rule, most notably in Australia[127] retailers may apply surcharges to any credit-card transaction, Visa or otherwise. In the UK the law was changed in January 2018 to prevent retailers from adding a surcharge to a transaction as per ‘The Consumer Rights (Payment Surcharges) Regulations 2012’.

Visa permits merchants to ask for photo ID, although the merchant rule book states that this practice is discouraged. As long as the Visa card is signed, a merchant may not deny a transaction because a cardholder refuses to show a photo ID.[125]

The Dodd–Frank Act allows U.S. merchants to set a minimum purchase amount on credit card transactions, not to exceed $10.[128][129]

Recent complications include the addition of exceptions for non-signed purchases by telephone or on the Internet and an additional security system called «Verified by Visa» for purchases on the Internet.

In September 2014, Visa Inc, launched a new service to replace account information on plastic cards with «token» – a digital account number.[130]

Products[edit]

Visa Credit Cards[edit]

Depending on the geographical location, Visa card issuer issue the following tiers of cards, from the lowest to the highest:[131]

- Traditional/Classic/Standard

- Gold

- Platinum

- Signature (Worldwide except Canada)[132]

- Infinite

- Infinite Privilege (Canada only)[133]

Visa Debit[edit]

This is the standard Visa-branded debit card.

Visa Electron[edit]

A Visa-branded debit card issued worldwide since the 1990s. Its distinguishing feature is that it does not allow «card not present» transactions while its floor limit is set to zero, which triggers automatic authorisation of each transaction with the issuing bank and effectively makes it impossible for the user to overdraw the account. The card has often been issued to younger customers or those who may pose a risk of overdrawing the account. Since mid-2000s, the card has mostly been replaced by Visa Debit.

Visa Cash[edit]

A Visa-branded stored-value card.

Visa Contactless (formerly payWave)[edit]

In September 2007, Visa introduced Visa payWave, a contactless payment technology feature that allows cardholders to wave their card in front of contactless payment terminals without the need to physically swipe or insert the card into a point-of-sale device.[134] This is similar to the Mastercard Contactless service and the American Express ExpressPay, with both using RFID technology. All three use the same symbol as shown on the right.

In Europe, Visa has introduced the V Pay card, which is a chip-only and PIN-only debit card.[135] In Australia, take up has been the highest in the world, with more than 50% of in store Visa transactions now made via Visa payWave.[136]

mVisa[edit]

mVisa is a mobile payment app allowing payment via smartphones using QR code. This QR code payment method was first introduced in India in 2015. It was later expanded to a number of other countries, including in Africa and South East Asia.[137][138]

Visa Checkout[edit]

In 2013, Visa launched Visa Checkout, an online payment system that removes the need to share card details with retailers. The Visa Checkout service allows users to enter all their personal details and card information, then use a single username and password to make purchases from online retailers. The service works with Visa credit, debit, and prepaid cards. On November 27, 2013, V.me went live in the UK, France, Spain and Poland, with Nationwide Building Society being the first financial institution in Britain to support it,[139] although Nationwide subsequently withdrew this service in 2016.

Trademark and design[edit]

Logo design[edit]

The blue and gold in Visa’s logo were chosen to represent the blue sky and gold-colored hills of California, where the Bank of America was founded.

In 2005, Visa changed its logo, removing the horizontal stripes in favor of a simple white background with the name Visa in blue with an orange flick on the ‘V’.[140] The orange flick was removed in favor of the logo being a solid blue gradient in 2014. In 2015, the gold and blue stripes were restored as card branding on Visa Debit and Visa Electron, although not as the company’s logotype.[141]

Card design[edit]

In 1984, most Visa cards around the world began to feature a hologram of a dove on its face, generally under the last four digits of the Visa number. This was implemented as a security feature – true holograms would appear three-dimensional and the image would change as the card was turned. At the same time, the Visa logo, which had previously covered the whole card face, was reduced in size to a strip on the card’s right incorporating the hologram. This allowed issuing banks to customize the appearance of the card. Similar changes were implemented with MasterCard cards. Today, cards may be co-branded with various merchants, airlines, etc., and marketed as «reward cards».

On older Visa cards, holding the face of the card under an ultraviolet light will reveal the dove picture, dubbed the Ultra-Sensitive Dove,[142] as an additional security test. (On newer Visa cards, the UV dove is replaced by a small V over the Visa logo.)

Beginning in 2005, the Visa standard was changed to allow for the hologram to be placed on the back of the card, or to be replaced with a holographic magnetic stripe («HoloMag»).[143] The HoloMag card was shown to occasionally cause interference with card readers, so Visa eventually withdrew designs of HoloMag cards and reverted to traditional magnetic strips.[144]

Signatures[edit]

Visa made a statement on January 12, 2018, that the signature requirement would become optional for all EMV contact or contactless chip-enabled merchants in North America starting in April 2018. It was noted that the signatures are no longer necessary to fight fraud and the fraud capabilities have advanced allowing this elimination leading to a faster in-store purchase experience.[145] Visa was the last of the major credit card issuers to relax the signature requirements. The first to eliminate the signature was MasterCard Inc. followed by Discover Financial Services and American Express Co.[146]

[edit]

Olympics and Paralympics[edit]

- Visa has been a worldwide sponsor of the Olympic Games since 1986 and the International Paralympic Committee since 2002. Visa is the only card accepted at all Olympic and Paralympic venues. Its current contract with the International Olympic Committee and International Paralympic Committee as the exclusive services sponsor will continue through 2032 and 2020 respectively.[147][148] This includes the Singapore 2010 Youth Olympic Games, London 2012 Olympic Games, the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games, the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympic Games, the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, and the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games.

- In 2002, Visa became the first global sponsor of the IPC.[149] Visa extended its partnership with the International Paralympic Committee through 2020,[150] which includes the 2010 Vancouver Paralympic Winter Games, the 2012 London Paralympic Games, 2014 Sochi Paralympic Games, 2018 Pyeongchang Paralympic Games and 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games.

Others[edit]

- Visa was the jersey sponsor of Argentina’s national basketball team at the 2015 FIBA Americas Championship in Mexico City.[151]

- Visa is the shirt sponsor for the Argentina national rugby union team, nicknamed the Pumas. Also, Visa sponsors the Copa Libertadores and the Copa Sudamericana, the most important football club tournaments in South America.

- Since 1995, Visa has sponsored the U.S. National Football League (NFL) and a number of NFL teams, including the San Francisco 49ers whose practice jerseys display the Visa logo.[152] Visa’s sponsorship of the NFL extended through the 2014 season.[153]

- Until 2005, Visa was the exclusive sponsor of the Triple Crown thoroughbred tournament.

- Visa sponsored the Rugby World Cup first from the 1995 Rugby World Cup was held in South Africa until 12 years later, when the 2007 Rugby World Cup, was held in France.[154]

- In 2007, Visa became the sponsor of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The FIFA partnership provides Visa with global rights to a broad range of FIFA activities – including both the 2010 and 2014 FIFA World Cup and the FIFA Women’s World Cup.

- Starting from the 2012 season, Visa became a partner of the Caterham F1 Team. Visa is also known for motorsport sponsorship in the past: it sponsored PacWest Racing’s IndyCar team in 1995 and 1996, with drivers Danny Sullivan and Mark Blundell respectively.[155]

- Visa is currently a jersey sponsor of professional gaming (esports) team SK Gaming for 2017[156]

- Visa is the main sponsor of the Argentine Hockey Confederation.[157] The Visa logo is present on both the men’s and women’s playing kits.

See also[edit]

- RuPay

- UnionPay

- CIBIL

- Damage waiver

- Entrust Bankcard

- Visa Buxx

- Visa Debit

- Visa Electron

References[edit]

- ^ a b Li, Roland (November 6, 2019). «Visa to vastly expand SF headquarters with move to Giants waterfront project». San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Saini, Manya (November 17, 2022). «Visa promotes McInerney to CEO as Kelly moves to board». Reuters.

- ^ a b «U.S. SEC: Visa Inc. Form 10-K». U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. November 16, 2022.

- ^ «Visa Inc. 2021 Annual Report» (PDF). Visa Inc. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Visa Archived September 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Fisher, Daniel (May 25, 2015). «Visa Moves at the Speed of Money». Forbes. Retrieved May 1, 2016. This article is authored by a Forbes staff member.

- ^ a b c Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ a b «History of Visa», Visa Latin America & Caribbean. Archived November 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Thomes, Paul (2011). Technological Innovation in Retail Finance: International Historical Perspectives. New York: Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-203-83942-3.

- ^ «Map and List of VisaNet’s Data Centers». Baxtel.

- ^ Kontzer, Tony (May 29, 2013). «Inside Visa’s Data Center | Network Computing». www.networkcomputing.com. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Swartz, Jon (March 25, 2012). «Top secret Visa data center banks on security, even has moat». USA Today. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ «History of Visa». Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ a b c d Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 24. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 25. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 28. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 30. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 31. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 32. ISBN 9781476744896.

- ^ Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ a b Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ The Unsolicited Credit Card Act of 1970 amended the Truth in Lending Act of 1968 to ban the mailing of unsolicited credit cards. It is now codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1642.

- ^ Nocera, 15.

- ^ «Welcome to Barclaycard Cashback | Barclaycard». Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Nocera, 89-92.

- ^ Nocera, 90-93.

- ^ Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo; del Angel, Gustavo (2016), «The Dawn of the Plastic Jungle: The Introduction of the Credit Card in Europe and North America, 1950-1975», Economics Working Papers, Hoover Institution: 18

- ^ «VISA». The Good Schools Guide. TheGoodSchoolsGuide. February 8, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ «BankAmericard to become Visa», The Courier-Journal (Louisville KY), December 16, 1976, p. B 10

- ^ «BofA resurrects Bankamericard brand», San Francisco Business Times.

- ^ Paybarah, Azi (March 5, 2022). «Mastercard and Visa suspend operations in Russia». The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Visa, Inc. Corporate Site Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Visa plans stock market flotation», BBC News – Business, October 12, 2006.

- ^ Bawden, Tom. «Visa plans to split into two and float units for $13bn.», The Times, October 12, 2006.

- ^ Bruno, Joel Bel. «Visa Reveals Plan to Restructure for IPO», Associated Press, June 22, 2007.

- ^ «Visa, Inc. Complete Global Restructuring» Archived December 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Visa, Inc. Press Release, October 3, 2007.

- ^ «Visa files for $10 billion IPO», Reuters, November 9, 2007.

- ^ «Visa plans a $19 billion initial public offering». The Economist. February 25, 2008.

- ^ Benner, Katie. «Visa’s $15 billion IPO: Feast or famine?», Fortune via CNNMoney, March 18, 2008.

- ^ «Visa Inc. Announces Exercise of Over-Allotment Option», Visa Inc. Press Release, March 20, 2008. Archived July 21, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ «Visa IPO Seeks MasterCard Riches» Archived February 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, TheStreet.com, February 2, 2008.

- ^ «Visa Europe members exploring sale to Visa – WSJ». Reuters. March 19, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ «FAQs». Visaeurope.com. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ «Visa Inc. to Acquire Visa Europe» (Press release). November 2, 2015. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ «Visa Inc. Reaches Preliminary Agreement to Amend Transaction With Visa Europe». Visa Inc. April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ «Visa Inc. Completes Acquisition of Visa Europe». Visa Investor Relations (Press release). June 21, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ «Visa is acquiring Plaid for $5.3 billion, 2x its final private valuation». TechCrunch. January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ «With Plaid Acquisition, Visa Makes A Big Play for the ‘Plumbing’ That Connects the Fintech World». Fortune. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ «What Plaid’s $5.3 Billion Acquisition Means For The Future Of Fintech And Open Banking». finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Demos, Telis (January 14, 2020). «Visa’s Bet on Plaid Is Costly but Necessary». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ «Visa to acquire crypto-serving fintech unicorn Plaid for $5.3B». finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Noonan, Laura (November 5, 2020). «US justice department sues to block Visa’s $5.3bn Plaid takeover». Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ «U.S. sues Visa to block its acquisition of Plaid». Reuters. November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Ellis, Nicquel Terry (August 20, 2022). «Cryptocurrency has been touted as the key to building Black wealth. But critics are skeptical». CNN. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ «Visa: Crypto API Program Makes Crypto An Economic Empowerment Tool». PYMNTS. February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ «Visa Expands Digital Currency Roadmap with First Boulevard». Visa. February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ «Visa Moves to Allow Payment Settlements Using Cryptocurrency». NDTV Gadgets 360. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Visa Crypto Thought Leadership – Auto Payments | Visa

- ^ Visa Unveils Plans For Auto-Payments From Self-Custodied Wallets — The Defiant

- ^ «Visa Launches Foundation with Inaugural Grant to Women’s World Banking».

- ^ «Visa has launched an Accelerator Program for Fintech startups across Asia Pacific». Startup News, Networking, and Resources Hub | BEAMSTART. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ «Accelerator». www.visa.com.sg. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ «Fortune 500 Companies 2022: Visa». Fortune. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d «2008 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2009 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2010 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2011 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2012 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2013 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2014 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2015 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ «2016 Annual Report» (PDF).

- ^ Volkman, Eric (January 18, 2018). «Why 2017 was a Year to Remember for Visa Inc. — The Motley Fool». The Motley Fool. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ «2018 Q4 Revenue and Earnings» (PDF).

- ^ a b «Visa, Inc — AnnualReports.com». www.annualreports.com. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ «Visa Inc. Reports Fiscal Fourth Quarter and Full-Year 2021 Results» (PDF).

- ^ BBC News. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ a b No proof WikiLeaks breaking law, inquiry finds, Associated Press (January 26, 2011) Archived January 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Wikileaks’ IT firm says it will sue Visa and Mastercard». BBC News. December 8, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ «WikiLeaks supporters disrupt Visa and MasterCard sites in ‘Operation Payback’«. The Guardian. December 8, 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Adams, Richard; Weaver, Matthew (December 8, 2010). «WikiLeaks: the day cyber warfare broke out – as it happened». The Guardian.

- ^ UNifeed Geneva/Pillay Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, UN Web site. Retrieved on December 15, 2010.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (July 12, 2012). «WikiLeaks Wins Icelandic Court Battle Against Visa for Blocking Donations | Threat Level». Wired. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Commission, Australian Competition and Consumer (September 4, 2015). «Visa ordered to pay $18 million penalty for anti-competitive conduct following ACCC action». Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

- ^ «Complaint, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Home Depot USA Inc» (PDF). PacerMonitor. PacerMonitor. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ «ATM Operators File Antitrust Lawsuit Against Visa and MasterCard» (Press release). PR Newswire. October 12, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ «National Atm Council, Inc. v. Visa Inc., Civil Action No. 2011-1803 (D.D.C. 2017)». Court Listener. May 22, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ «Visa Check/MasterMoney Antitrust Litigation», Web Site. Archived April 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mallory Duncan (July 10, 2012). «Credit Card Market Is Unfair, Noncompetitive». Roll Call.

- ^ «Visa, Mastercard settlement means more flexibility for merchants». Marketplace. American Public Radio. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- ^ «Commission exempts multilateral interchange fees for cross-border Visa card payments» (Press release). European Commission. July 24, 2002. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ «Competition: Commission sector inquiry finds major competition barriers in retail banking» (Press release). European Commission. January 31, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ «Antitrust: Commission initiates formal proceedings against Visa Europe Limited» (Press release). European Commission. March 26, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ UOKIK. «UOKiK – Home». www.uokik.gov.pl.

- ^ «Sector inquiry in the banking sector». February 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Jan Strupczewski; Foo Yun Chee (December 17, 2014). «EU agrees deal to cap bank card payment fees». Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ SEPA: a busy year is coming to its end and another exciting year lies ahead (Speech). November 25, 2010.

- ^ «Trouw.nl».

- ^ «Class Settlement Preliminary Approval Order pg.11» (PDF). U.S. District Court. November 27, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Longstreth, Andrew (December 13, 2013). «Judge approves credit card swipe fee settlement». NBC News. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «Visa, Mastercard $6.24B settlement gets preliminary okay from court». Seeking Alpha. February 22, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «Rynek kart czekają zmiany (wersja do druku)» (in Polish). Ekonomia24.pl. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ «IKO: rewolucyjny system płatności mobilnej od PKO BP – Banki – WP.PL». Banki. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ «Płatności mobilne w Biedronce – Tech – WP.PL». Tech. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ «Mobile Payments – Bilet w komórce». Skycash.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Sidel, Robin (June 16, 2016). «Visa Defends Fees in Wal-Mart Canada Dispute». Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Evans, Pete (January 5, 2017). «Walmart strikes deal with Visa to settle credit card fee dispute». CBC.

- ^ Morris, Chris. «Kroger Bans Visa Cards at 250 Additional Stores». Fortune. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Peterson, Hayley (October 30, 2019). «Kroger has reversed its ban on Visa credit cards after previously accusing the company of ‘excessive fees’ that ‘drive up food prices’«. Business Insider. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Kendall, AnnaMaria Andriotis and Brent (March 19, 2021). «WSJ News Exclusive | Visa Faces Antitrust Investigation Over Debit-Card Practices». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ «Report: DOJ investigating Visa over debit card business». The Washington Post. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 20, 2021.[dead link]

- ^ Copeland, Brent Kendall and Rob (October 21, 2020). «Justice Department Hits Google With Antitrust Lawsuit». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Torry, AnnaMaria Andriotis and Harriet (June 21, 2020). «The Credit-Card Fees Merchants Hate, Banks Love and Consumers Pay». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ «Week in review.» The Daily Journal. January 3, 2009. Retrieved on February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Leuty, Ron (September 13, 2012). «Visa moving headquarters from San Francisco to Foster City». San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

[Visa] said Thursday that it is closing its headquarters in San Francisco and moving about 100 employees back to its Foster City campus, effective October 1. […] The bulk of the company’s employees—3,100 of more than 7,700 worldwide… are in Foster City.

- ^ a b «Visa finds a passport to the future San Mateo Company bets on ‘SMART’ cards that will exchange information, not just money.» San Jose Mercury News. Monday August 7, 1995. 1F Business. Retrieved on February 2, 2011. «Visa’s headquarters remained in San Francisco until 1985 when it relocated to San Mateo. Then, two years ago, it began consolidating scattered sites throughout San Mateo in nearby Foster City with […]».

- ^ Ladendorf, Kirk (December 11, 2012). «Visa confirms plans for Austin offices». Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ Wells, Arnold (May 14, 2019). «Visa grows tech center in North Austin». Austin Business Journal. Retrieved September 15, 2019.